Battling Drug Addiction in the Tiniest of Patients

Dr. Alison Rentz helps change the culture of care in the NICU

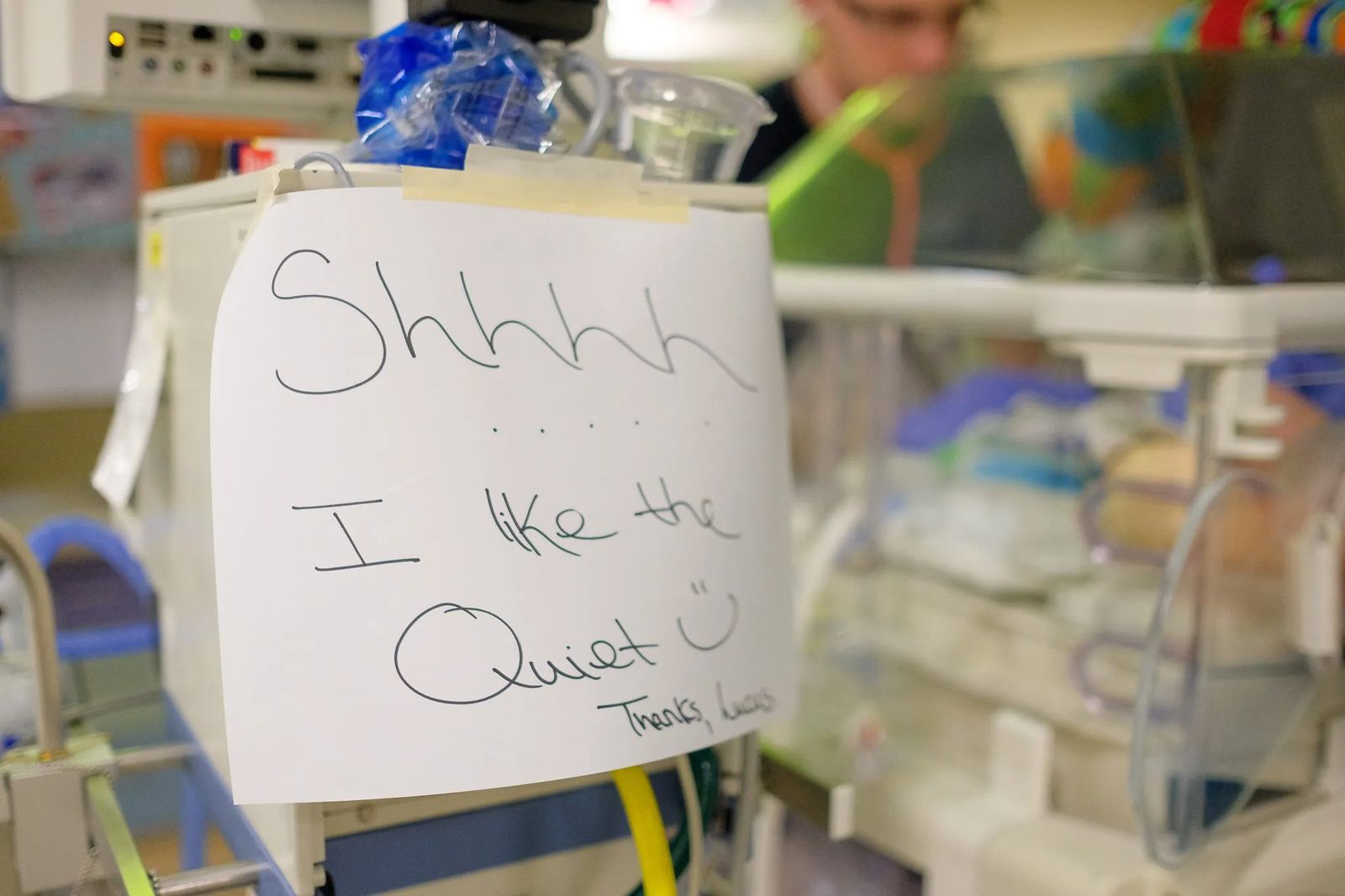

When Neonatologist Dr. Alison Rentz makes her rounds at Saint Vincent Healthcare, she’s checking up on some the city’s most fragile residents. Her patients’ tiny heads don hats in shades of soft pink or baby blue. Tubes can be seen delivering nourishment as incubators try to keep their little bodies with paper-thin skin warm. They weigh a few pounds if they are lucky and each minute they breathe in the sterile air of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, it is one more victory after their rocky start in life.

“I love caring for families and newborns and helping them make the difficult journey through the newborn period in the hospital,” Dr. Rentz says with passion.

Some days, the journey is difficult.

“We’ve seen an increase in opioid use in pregnant women. The babies then do have trouble with withdrawal after they are born,” Dr. Rentz says and adds, “There has been a large rise in methamphetamine in Montana recently. We’re seeing that too. When pregnant moms use meth, babies are delivered early with a lot of complications.”

For the medical providers caring for these babies in the neo-natal intensive care, in labor and delivery and in the newborn nursery at St. Vincent Healthcare, they are the first line of defense. After all, signs of drug abuse can, with prompting, lead a mom to recovery. It hasn’t, however, always been that way.

“When I started, once a baby came in with drugs in their system, we rarely saw the mom and we didn’t involve her in care,” R.N. Marcella Tatarka says. She’s worked for more than 37 years as a neonatal intensive care nurse — both here and in California. “A lot of what we did was done behind the scenes. We weren’t up front with the parents. No one said, ‘Your child is here because of your drug addiction.’”

After seeing a national trend to envelop the entire family and get to the heart of drug addiction, Dr. Rentz championed training to put St. Vincent Healthcare on the map as an accredited Center of Excellence for Neonatal Abstinence Care. St. Vincent Healthcare’s program is one of 45 in the nation and the only one of its kind in Montana. The goal is to help these babies and families to fight the epidemic and heal in the process.

“I’ve seen a lot of people change their lives based on having a newborn baby,” Dr. Rentz says. “Seeing their baby born because of poor prenatal care or because of drugs, I see how that changes a person.”

Prepping for this designation was a huge undertaking on the part of multiple hospital departments. It took four years for staff to complete the web-based training. St. Vincent Healthcare belongs to the Vermont Oxford Network, a nonprofit collaboration of health care professionals working together to change the landscape of neonatal care. Starting in 2013, Dr. Rentz says it was the network’s mission to address drug abuse in infants and “really get people on board in terms of family-centered care.” The hope was that with extra training and attention, babies would ultimately spend less time in the hospital because of better treatment methods. Families would also become a part of the solution rather than being the perceived problem.

“It’s a whole team here,” Dr. Rentz says. It’s a team where care looks at the big picture. She says, “What did that mother go through in her own life? Was she abused? Was she in a bad situation? How did she get to this point? We are trying to work as a team to really figure out how we can break the cycle of drug abuse, neglect and child abuse in general.”

Trying to get to the heart of the matter isn’t easy, especially when it’s your job to care for a drug-addicted baby. That preemie might not even weigh a pound. The tiny child might be jittery, fussy, or, in extreme cases, suffer seizures. The infant will often be plagued with gastrointestinal distress or suffer fevers because of a revved up metabolism.

“When I first started in neonatal nursing many years ago, we didn’t think babies had enough neuropathway integrity to feel pain, so babies never got pain medications,” Marcella Tartarka says. “Back then, heroin was huge where I was in California and those withdrawals were ugly. Now we are seeing heroin come back. But, we are treating babies with medications to help with the pain and symptoms from withdrawal.” Studies have shown less pain means less distress for an infant, allowing these babies to gain their strength at a quicker pace.

“It is hard to see children when they are affected,” Dr. Rentz says. “When they come into the newborn ICU, we have them here and we have a captive audience. It is hard when there is no one visiting a baby. But, we try to shower the babies with love when they are here and do what we can.” Dr. Rentz says it would be easy to get depressed about some of the statistics. Ten to twenty-five percent of all the children in her NICU on any given week face symptoms of drug addiction. Instead, Dr. Rentz says she is seeing her colleagues become empowered knowing there is more that can be done to change a life. She says, “I do think if we weren’t trying to change, it would be heartbreaking.”

The unit works closely with Child Protective Services and drug treatment providers to make those connections and help parents face their addictions.

“I’ve seen a lot of success stories – seeing moms get into treatment, getting themselves clean and getting a job,” Dr. Rentz says. “Obviously, that does not happen every time but if it happens once you’ve made a big difference in a whole family’s life. It could be countless numbers of people that you’ve changed.” As a mother of three herself, Dr. Rentz says with conviction, “I feel like it is at least worth giving it a try.”

In time, Dr. Rentz hopes the community starts to see how drugs continue to impact our community.

“It’s no longer shooting up heroin in a back alley. It is getting hooked on a prescription opioid that then is over prescribed and being addicted that way, Dr. Rentz says. “That’s the current problem.”

Not long ago, Dr. Rentz witnessed firsthand just how this specialized training is starting to pay off.

“There was one mom who struggled and went into drug treatment but diligently kept pumping until she was able to provide a negative drug screen. We were able to use her use her breast milk and she successfully breastfed her baby. Just a couple of years ago there would have been no way we would have even considered that,” Dr. Rentz says. She adds that these small changes could be just what a mom needs to believe in herself again. “Seeing her be able to go home with her baby and breastfeed her baby was, to me, the story of what we are trying to do.”

Every time a wee one goes home, it is with the full knowledge of the fight each one of them waged and won. Dr. Rentz and the rest of the team in the NICU can say goodbye knowing they helped a family leave with the best possible chance at success. “Those are the best possible days,” Dr. Rentz says. “It’s still awe inspiring what these babies survive, especially the extreme pre-term babies. They are true warriors.”

Join Dr. Alison Rentz and more than a dozen other providers for ‘The Art of Women’s Health’. This just for women health event is set for Thursday, May 4 at the Yellowstone Art Museum. Women will have the opportunity to connect one-on-one with providers from a wide range of specialties from labor and delivery to mammography and heart health. Be inspired by FutureSYNC International’s Wendy Samson and become informed about women’s health issues. When a woman has her health, she’s able to create extraordinary works of art. So, grab your girlfriends and learn more about how you and your health can become a masterpiece. The event takes place from 5:30 to 8:30 PM. Cost is $12 per person and includes gourmet hor 'd oeuvres and specialty beverages. Register at svh.org/art as space is limited.