Getting Enough Fiber?

It’s woven deep into Montana’s agriculture

If you look at the Montana landscape, you’ll see fluffy animals grazing on pastures far and wide. Many of these creatures are being raised for meat, but ranchers are also supplying an indispensable product to fiber artists worldwide. Fiber — of all varieties — is woven deeply into Montana’s history.

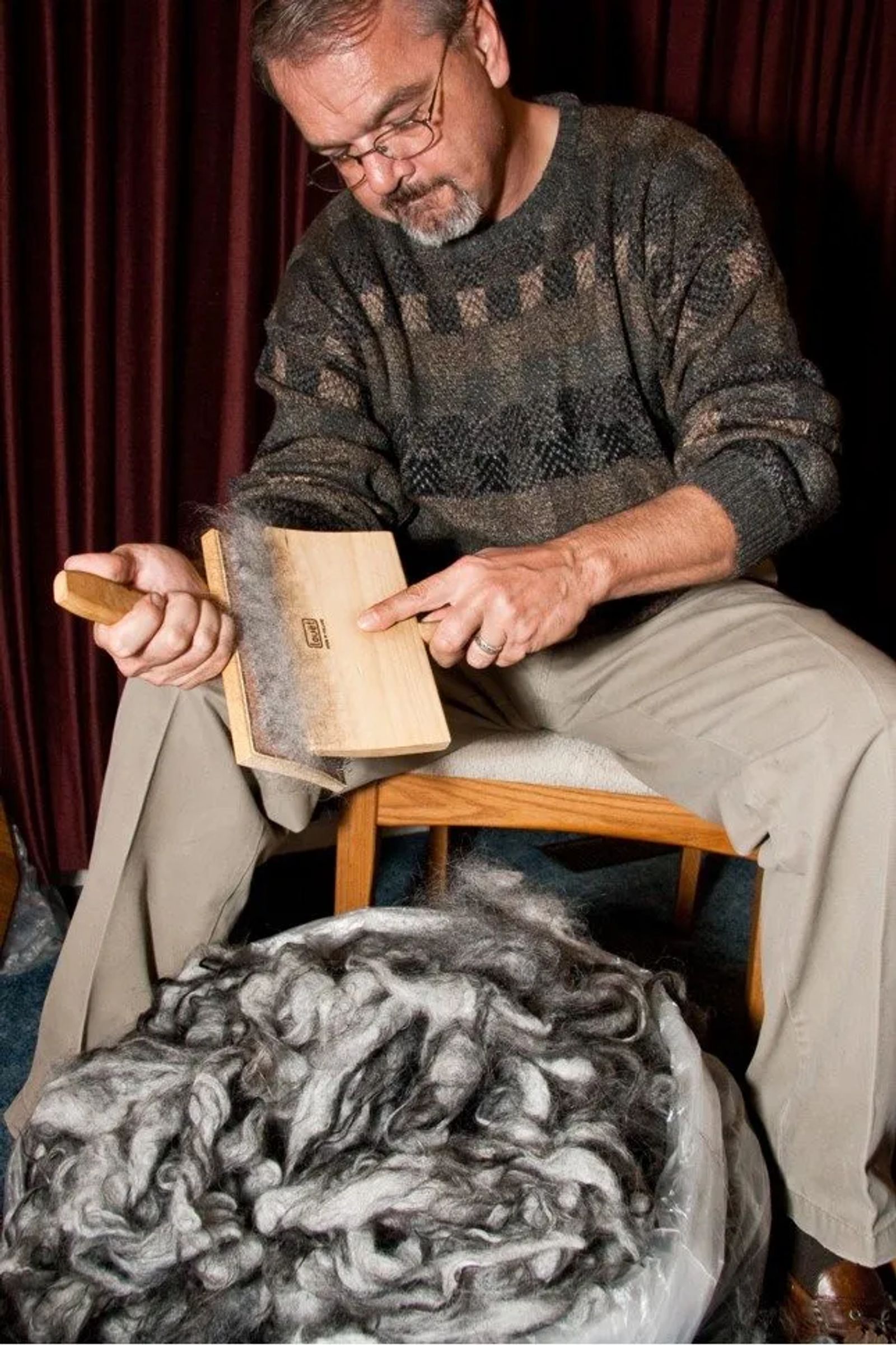

“It’s hugely popular. It’s like a sub-culture,” says Randy Glick, a Great Falls’ fiber artist inducted into the Montana Circle of American Masters in the Visual Folk and Traditional Arts. He’s been working with fiber for decades. He credits this welcoming community, whose members are more than happy to share how to spin yarn, weave and felt. “I think the appeal is because it is quintessentially Montana,” Glick says. “We have a ready supply of every wool available.”

From Soay sheep, one of the first domesticated breeds that shed their fleece instead of requiring shearing, to hybrids bred to meet the demands of today, sheep have shaped Montana agriculture. Glick points out that Paris Gibson, the founder of Great Falls, came out to Montana to raise sheep, not to create a town. When Gibson and his family migrated to Montana from Minneapolis in 1879, they raised sheep near Fort Benton, and in 1883 he was elected president of Montana Wool Growers Association, a position he held for over 20 years.

While sheep have proved to be an excellent range management tool, Glick says more producers are trying to find the balance between meat sheep and fiber animals. “We have meat sheep (such as Suffolk) and they still need to be shorn,” he says, but it’s nearly impossible for the producer to earn enough money from the small fleece to pay for the shearing. When you have a fiber sheep that also works for meat, you have the best of both worlds in value-added agriculture.

Glick uses the wool from Targhee sheep raised along the Smith River to produce his yarns. “Targhee were developed for their fine wool and good meat,” he says. “Then, it’s cost-effective.” Targhee are also known for the softness of their fleece, measured in microns. “If you want it against your skin, you want a micron less than 30,” Glick says, and Targhee typically are in the 22-24 micron range.

Glick purchases all the fleece from the ranch, providing a ready market for the producer since Glick doesn’t require the cream of the crop like many other fiber artists. Plus, he’s able to pay the sheep rancher considerably more per pound than she would receive at the wool pool, where a bulk fleece is sold.

While there are smaller processing mills within Montana, Glick sends his fleece to Mountain Meadow Wool Mill in Buffalo, Wyoming, where they wash, cord and comb the fleece. For every 10 pounds, he expects to receive approximately 4-5 pounds in return after the grease, ruined fiber and vegetable matter are removed.

After he works his magic spinning, he can sell the naturally colored wool or dye it to fit his various color wheels. He can also custom dye for fellow spinners at the Yarn Bar in Billings and the Fibre House in Great Falls, as well as shows throughout the region. He also makes wool dishrags from the Targhee wool since odorous bacteria doesn’t tend to grow on wool as it does on cotton.

Although wool takes center stage in the fiber world, it’s by no means the only player. Glick points out a necessary distinction: “All wool is fiber, but not all fiber is wool. Wool only comes from sheep.” Fiber artists will work with everything from cat to musk ox, and some of the popular choices truly have a Montana flair.

“There are a lot of different fiber animals in Montana. The other big one is alpaca. There are a lot of alpaca people in Montana,” he says. When buying alpaca fiber, fiber artists will oftentimes purchase the entire fleece. “It’s not unheard of to get the animal’s name on the fiber you buy.” Glick adds, “You see some yak, but not a whole lot.” He says bison is also growing in popularity. “They have an undercut that is amazing. It’s soft … and expensive.” Bison fleece is hypo-allergenic, water wicking and nearly as soft as cashmere. The only trick here is finding an agreeable bison, willing to let you collect the fiber as it molts. As a result, it’s pricey.

But for hardcore fiber artists, price, particularly for special projects, isn’t always a deterrent. “I paid $75 an ounce for qiviut from musk ox,” he says. “Some people pay through the nose for fiber and yarn. The vast majority of fiber artists don’t do it for the money — it’s the passion.”

You’ll see that passion if you happen to hit up one of the fiber festivals or conferences around the state. There, you’ll see the handiwork from fiber artists who have spent countless hours learning, practicing and demonstrating their obsession surrounded by an energetic crowd of enthusiasts.

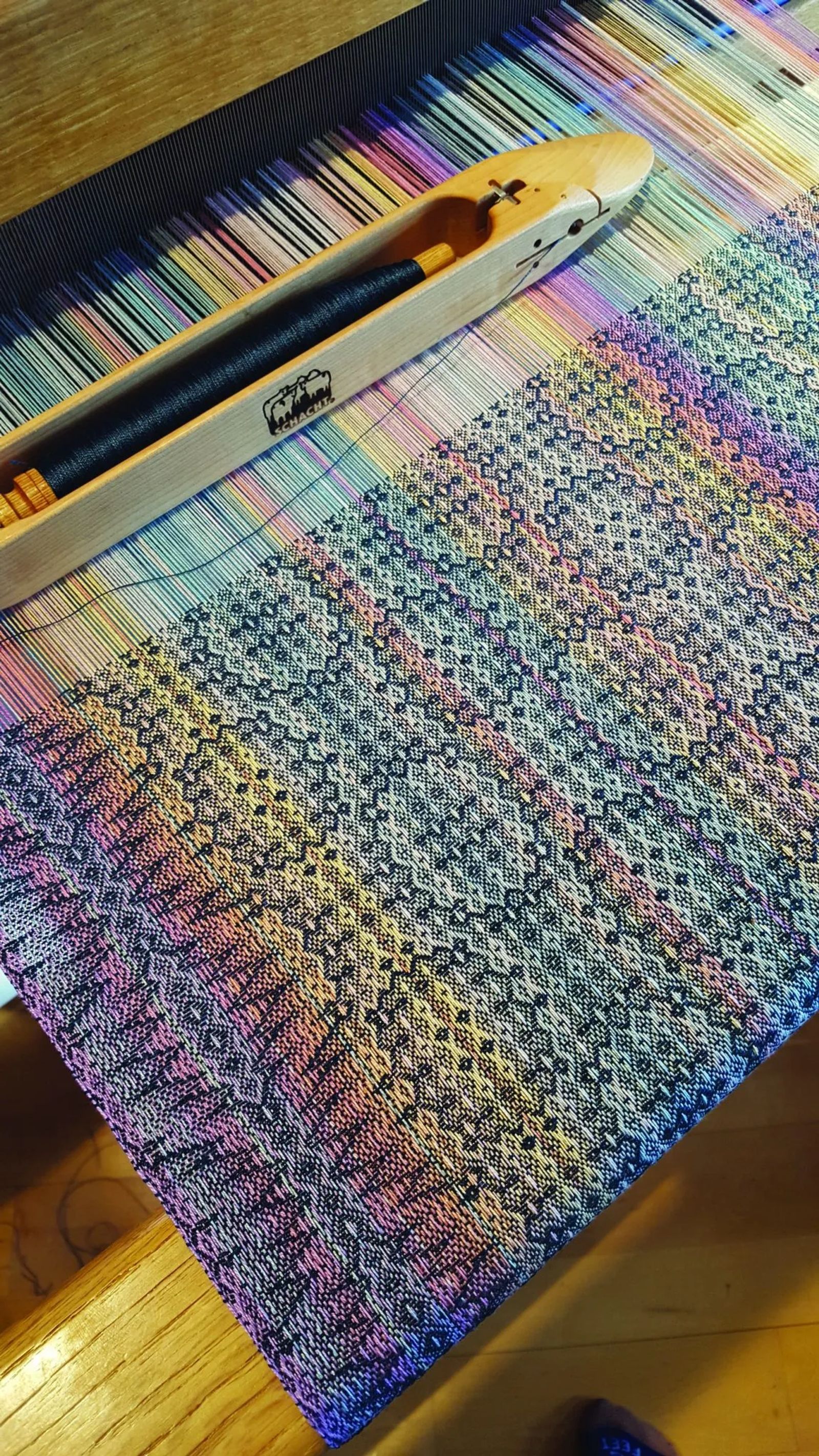

Susan Lohmuller, president of the Montana Association of Weavers and Spinners, says when it comes to fiber artists, Montana produces the cream of the crop. “There is a lot of local talent. There are top-notch teachers in the state,” she says, adding that fiber lovers become completely immersed in the craft because there is always something new. Lohmuller says, “You can never learn everything there is to learn about weaving. It’s such a deep subject. Weavers who were mentors to me were still taking classes in their 80s.”[/caption]

Susan Lohmuller, president of the Montana Association of Weavers and Spinners, says when it comes to fiber artists, Montana produces the cream of the crop. “There is a lot of local talent. There are top-notch teachers in the state,” she says, adding that fiber lovers become completely immersed in the craft because there is always something new. Lohmuller says, “You can never learn everything there is to learn about weaving. It’s such a deep subject. Weavers who were mentors to me were still taking classes in their 80s.”[/caption]

Working with fiber resonates deeply with everyone who creates with it. “You connect at a certain level with generations,” Lohmuller explains. “Older generations wove for practical reasons, but they were adding beauty to their lives.” And Lohmuller can attest firsthand that this beauty is still being woven throughout Montana today.

IF YOU’D LIKE TO LEARN MORE about what’s happening in the world of fiber artists, check out the Montana Association of Weavers and Spinners at montanaweavespin.org.