The Task Force: The Government Efforts

MIP Task Force works together to face the problem

Ask anyone playing a role in the Montana Missing Indigenous Persons Task Force, and they’ll tell you time is of the essence. If you ask victims’ families waiting for answers, time can’t move quickly enough. If you ask law enforcement, there’s no time like the present to shore up critical resources and training needed to fill the investigative gaps in missing-persons cases. And, if you ask those in the legal realm, the clock is ticking to get recommendations together so legislation can be drafted before the 2021 Montana legislative session.

“It’s important that we step up our timeline,” Deputy Attorney General Melissa Schlicting told a crowd of about 40 gathered for a two-day meeting in Billings in mid-February spotlighting the state’s missing indigenous people.

The Looping in Native Communities Act, passed by the 2019 Legislature, helped form the task force. Members from each Montana tribe have a voice at the table along with those within the Department of Justice tasked with stemming the number of Missing and Murdered Indigenous cases.

“What some people may not recognize is that if it is not reauthorized by the next legislature, this task force will not go past June of 2021,” Schlicting said.

That was not welcome news for Lorna KnowsHisGun, a self-described MMIW activist, sitting in the front row. She listened to Bureau Chief Gary Seder with the Department of Justice Crime Information Bureau talk about how law enforcement pushes information about missing persons cases in Indian country. Lorna jumped in, saying, “We need logistics. We need boots on the ground. We don’t need someone to hand us a flier and to tell us ‘beware.’ These families need help. Let’s stop talking and let’s start to do something about this epidemic.”

Insufficient resources seemed to be just one issue that Native American families present had with the system. Many cite racism, poor reporting of missing persons, jurisdictional gaps between local, tribal and federal agencies and a lack of manpower altogether.

It’s the task force’s job to create the framework to help beat back each one of those problems.

“I know a lot of you are frustrated,” Seder told the crowd. “I understand your concern. We are there. We do have resources available. Our biggest thing is, we just need to get a request from law enforcement agencies. Some of them do request it and some of them don’t.”

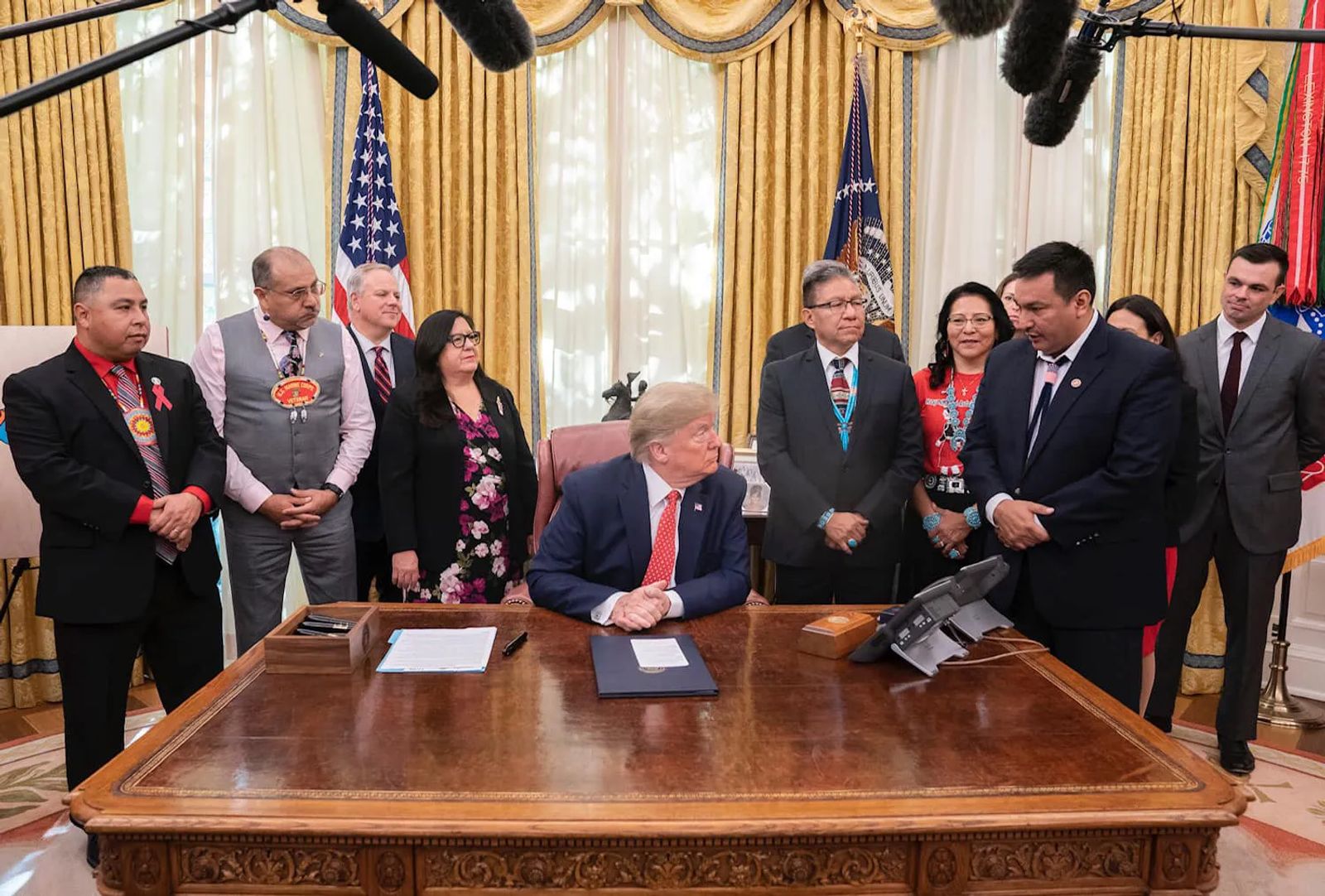

Crow Tribal Chairman A.J. Not Afraid was standing at President Trump’s side in the oval office last November when the president signed an executive order creating a national MMIW Task Force and response plan. When Not Afraid got news of the state’s task force meeting, he cleared his schedule to be there. (See sidebar on Operation Lady Justice)

“The crazy thing is, Indian nations have always been trying to make headway with BIA, and the other entities that have authority on the reservation,” Not Afraid said. “A lot of the tribes have become disgruntled because they felt that when there have been missing or murdered person cases, it hasn’t been sought after or there wasn’t much communication back to families. It seemed like no one really cared when these issues came up with law enforcement in the past.”

During the meeting, a statewide list of missing indigenous people was circulated. There were 38 active cases on the list.

“I am very passionate about this,” Not Afraid said, citing the roughly 20 names he realized were missing from the list. “A lot of those members who are not on the list are closely related to me. I’m not doing this from a political standpoint. I am doing it from a family standpoint.”

While the task force is looking to form an inter-jurisdictional response, Not Afraid talked about his desire to seek training for the Crow Tribe’s search and rescue team that, to date, has only gotten on the job training. He’s also hoping to hire at least 40 additional tribal police officers in the near future

“We can’t just look the other way,” Not Afraid said.

Former FBI Agent Ernie Weyand spent many years investigating crime in Indian Country. After retiring, he jumped into the role of the U.S. Department of Justice’s Missing Indigenous Person coordinator, working as the first coordinator in the nation to address the issue. He’s already met with tribal leadership, law enforcement and victims’ family members on every reservation in Montana.

“This is a community problem that law enforcement alone isn’t going to solve,” Weyand said. “It needs to start on the prevention side when there is a response. The most effective response is a community response that includes law enforcement as being part of the solution.” He said he can’t provide manpower but he can help with training and capacity building so that communities can be ready to move when an emergency arises.

After listening to all the concerns and comments, Schlicting said the meeting just reaffirms what she already knew. There needs to be a better understanding of what resources exist and what resources don’t. So far, the task force has completed six community meetings with six more on the calendar.

“We have a long way to go,” Schlicting said. “It’s touching and humbling work and I’m honored to be a part of this task force. Any amount of comfort and clarity we can provide families helps.”

THE LEGISLATIVE WORK

The ways lawmakers are working to stop MMIW

OPERATION LADY JUSTICE

Last November, President Donald Trump signed an executive order paving the way for MMIP (Missing and Murdered Indigenous People) coordinators in 11 Western states including Montana. The coordinators will work closely with federal, tribal, state and local agencies to develop protocols for a more coordinated law enforcement response to missing-person cases. The plan calls for the deployment of the FBI’s most advanced response teams when needed, improved data collection and analysis, and training to support local response efforts.

SAVANNA’S ACT

This bill, which passed out of the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, would require every state’s U.S. attorney to implement a guideline to follow when a Native woman is reported murdered or missing. It requires collaboration with tribal law enforcement, tribal government, and state and local law enforcement. The act also calls for improved law enforcement training and access to an inter-jurisdictional database. The bill sponsored by Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska has 29 co-sponsors, including Montana Sens. Steve Daines and Jon Tester. It’s currently on hold, waiting to be put on the Senate’s calendar for a vote.

NOT INVISIBLE ACT

This act requires the Department of the Interior to coordinate violent crime prevention efforts across federal agencies. It also calls for a commission made up of federal agencies, tribal leaders, tribal law enforcement, mental health providers, survivors and state and local law enforcement. The commission would come up with recommendations to improve the response to MMIW, human trafficking and violent crime in Indian Country. Both of Montana’s senators are listed as co-sponsors of the bill that’s currently waiting to be put up for a vote in the senate.

MAY 5, 2020

National Day of Awareness for Missing & Murdered Native Women and Girls

A day designated by the U.S. Senate to shine a light on the high rate of homicides of Native American women. Sens. Daines and Tester co-sponsored the resolution last year in memory of Hanna Harris, a Lame Deer woman murdered on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation seven years ago. Both senators plan to introduce the resolution again this year.