A Beautiful Gift

Dr. Sarah Stewart’s own trauma is giving others healing & hope

Dr. Sarah Stewart calls some of her patients her “bendy” people. Since her license to practice medicine is active only in Montana, her patients travel from a six-state region and, every now and then, from even longer distances just to see her.

These patients have often been funneled through a whole host of doctors and specialists in search of answers for their debilitating pain, hypermobile joints, strange allergies, dizzy spells and gastrointestinal issues. Those are just a few on the long list of potential symptoms. Doctors before her came up empty on a diagnosis. Sarah, however, has come to vividly see the signs of Ehlers Danlos Syndrome, a genetic connective tissue disorder.

On any given week, she’ll consult with six to eight new Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (EDS) patients — adding to her already over-capacity load of family practice patients.

“I think right now I am somewhere around 450 patients at this point, patients with Ehlers Danlos,” she says. And, she adds, “One of the things I absolutely love about what I get to do is helping my patients feel valid. I see what you have and it’s real. Just because other people haven’t understood it. Just because you’ve gotten the message that it’s all in your head. That message won’t come from me here.”

How Sarah got here — as one of the primary EDS caregivers in the Pacific Northwest — is the miraculous part of her story. It was a tragic twist of fate that left her, her husband and their eldest daughter on the brink of death along a dark and foggy section of Highway 212 near Roberts. It was March 31, 2017. The time was just past 9 p.m. Sarah, her husband, Kit, and their three daughters, Miriam, then 17 months old, Faith, then 4, and Naomi, then 14, were headed home to Luther.

“I had seen this truck driving crazy,” Sarah says. “He came up on me fast and was trying to pass me. He had gotten all the way up to my driver’s side mirror. I could see there was an oncoming car and I said to myself, ‘Oh, my gosh, what is this guy doing? He’s going to kill someone.’” The man slammed on his truck’s brakes and got behind the Stewart’s SUV. When he tried to pass again, she says, his vehicle hit the driver’s side rear quarter panel while traveling at an estimated 110 mph. Sarah would later learn that the driver was drunk, with a blood alcohol level that was three times the legal limit.

“The force of that put my car into a spin, and while I was being simultaneously hit by the oncoming car, which was a Suburban, we were being hit by him again as he was driving off,” Sarah says. The force ejected her husband out the vehicle’s back window. “He was thrown 70 feet onto the highway in the middle of the north-bound lane.”

Naomi, who was sitting on the side of the car that took most of the impact, was crumpled up in the front passenger seat. Sarah believed she was gone. Her two younger daughters were awake and screaming.

“I could tell that I was not physically OK, but I was in shock at that point,” Sarah says, adding that she knew her pelvis was broken. She had a strong feeling she had broken ribs, but as she screamed for help, didn’t realize she was doing so with a collapsed lung.

“Faith unbuckled herself. She was right behind me screaming, ‘Where’s daddy? Where’s daddy?’ She was crawling around the back of the car in the glass looking for him because she had watched him being ejected.” She adds, “As a physician, and anyone who has done any kind of ER work, if he wasn’t in the car, he had to have been dead. That’s just what I thought.”

As ambulances arrived on the scene and medical personnel rushed to the Beartooth Billings Clinic in Red Lodge. The events of the next few days would prove to be something no one would have predicted.

Not only was Naomi alive, she woke up and walked from the scene with a broken first rib. When Sarah heard that news, she knew the impact Naomi sustained had to be incredible. “It takes the most force of anything to break that bone of any bone in the body,” Sarah says.

Kit, who had been tagged by EMTs as “black,” which means unsalvageable, was released from the hospital with a laceration on his neck that missed all major vessels. A scan had shown a small brain bleed, Sarah says, but “48 hours later, they couldn’t see it anymore.” When asked if that fact was miraculous, Sarah says, “Completely. I’ve actually looked back at his images and said, really? There’s not even a bruised organ? Nothing? Nothing in him and he flew from the car? He’s not a small dude – 230 pounds — flying from the car onto the highway.” She adds, “None of us could understand, outside of a miracle, that any of us could have lived through what happened.”

As Sarah spent four months off work healing her broken bones, Naomi’s health started what would become a four-year downward spiral.

“Her body wasn’t really recovering and all the things we kept doing to help her get better were making her worse,” Sarah says.

What the family didn’t know then was that Naomi was born with Ehlers Danlos Syndrome. Those with EDS have hypermobile ligaments and joints, and Sarah knows now that if Naomi didn’t have EDS, she would not have survived the crash.

“It’s very common in people’s history with Ehlers Danlos when they’ve been in these really severe wrecks that others around them will die but they won’t,” Sarah say. It was the “bendy” nature of her joints that saved her. “A normal person would have snapped. It would have broken my neck.”

From the fall of 2017 to the early part of 2018, Naomi was losing weight. She had no appetite. She suffered severe migraines. “She would feel like her head weighed a million pounds,” Sarah says. She underwent surgery to remove her first rib, which refused to heal. That caused massive muscle spasms and even more pain.

“She couldn’t get out of bed,” Sarah says. “She was nearly passing out regularly. She couldn’t stand in the shower. Her heart was racing all the time.” Naomi began to sink into despair.

“We kept going to doctors and they kept saying it wasn’t working or they’d say nothing was wrong, and I started to think it was all in my head,” Naomi says. “It was very hard to keep going.”

“I remember praying, ‘God, please give me something. I don’t even know what else to do. Everything we’ve done has made it worse,’” Sarah says. Lying awake one night, she had a flash of a memory. “I remembered this thought from medical school about collagen disorders and cervical instability.”

It was the spark of hope she needed.

“I start Googling – cervical instability, adolescent trauma. What came up is all of these articles in PubMed (National Institutes of Health) written by one of the neurosurgeons in the Ehlers Danlos Society,” Sarah says. “I started reading the article and I said, ‘Oh my gosh, I am reading my daughter’s story.’”

From that one article came more research, digging for information on experts in the field. Sarah found them and called each one of them. Surprisingly, she says, they all took her call. One of them was the neurosurgeon whose article started Sarah down this road. He referred her to a physical therapist in Rhode Island, and that therapist was able to see Naomi the following week. In just one session, he helped Naomi adjust her neck with a few simple movements.

“She could feel warm going all down her body and for an hour she didn’t have pain and it was the first time in a year that she had any relief,” Sarah says.

-2_touchupweb.jpg?fit=outside&w=800&h=1200)

Naomi ended up staying at the Ronald McDonald House in Providence for the next four months, working with Ehlers Danlos-trained physical therapist Michael Healy to continue her rehabilitation. An EDS-trained neurologist worked on calming down her autonomic nervous system disfunction, the part of the body that regulates involuntary processes like heart rate, blood pressure and digestion. In time, Naomi would have surgery to deal with what’s called tethered cord. After the wreck, the end of Naomi’s spinal cord became weighted down and was under constant tension, causing a chain reaction of unbearable symptoms.

“It completely set her on the course of being able to get strong again,” Sarah says.

Today, Naomi isn’t completely free of pain, but she understands her body’s limits and now knows how to reduce the pain and flare-ups.

“I am starting to feel like I can live and do things,” Naomi says. “Now, I always monitor my energy limits of what I can and can’t do in a day.”

“I would never have believed that she was going to be able to go to college,” Sarah says, smiling softly at her daughter. Naomi, now 20, will graduate in the fall with a degree in English from St. Catherine University, a small private women’s college in St. Paul, Minnesota. She’s hoping to go on to earn a master’s in fine arts with an emphasis in creative non-fiction writing. She hopes to one day write a memoir.

“Throughout my accident, I’ve been writing this whole time,” Naomi says. “In college, I write a lot about living with chronic illness and it resonates with a lot of people in different ways.” She wants her story to give others hope. “Starting with the accident and the discovery of EDS and how does faith build into that?” Naomi says of her potential book. “How do you live hurting all the time, believing that there is a God who loves you?”

Throughout this journey, Sarah faced her own set of intense battles. “I struggle still with pretty profound post-traumatic stress,” she says.

“She experienced everything,” Kit says. “Saw everything. Heard everything. Felt everything and witnessed everything afterward.”

“I felt my bones breaking,” Sarah adds. “For months, I had debilitating flashbacks and nightmares.” She doesn’t like chilly, wet nights, emergency lights or the sound of an ambulance. There were times in the months following the crash that driving along that stretch of road would make her physically ill.

“I had to change my work schedule because I used to start work at 7 in the morning and I’d be driving in the dark. Being in the dark, I would all of a sudden see Naomi crumpled up and I was in that moment again where I thought she was dead,” Sarah says. “I had to do a lot of work in that time period to work through those things,” Sarah adds. “It was totally God’s mercy and therapy.”

Meantime, as Sarah was learning about her daughter’s syndrome, she started seeing things in her patients that, up until then, were medical mysteries.

“I was learning and learning and learning and recognizing symptoms associated with Ehlers Danlos. I would be talking with my nurse Katrina and she would say, ‘Oh, that kind of sounds like so-and-so patient we have.’ I said, ‘You know, you’re right,’” Sarah says.

Sarah’s first patient turned out to be right under her nose. Her medical assistant, Monica Todd, had started having inexplicable health issues as a teen.

“I started to notice joint pain. I started having dislocations,” Monica says. “They told me it was growing pains. It was normal. Everything was fine.” In her 30s, she started looking for specialists to help pinpoint her health issues. “I started getting passed from doctor to doctor. They did testing and they could never figure out what was wrong. Everything looked normal.”

Four years ago, she started — by complete chance — working as Sarah’s medical assistant at Shiloh Family Medicine. “I started telling her about all my symptoms,” Monica says. “It was so bad I could hardly get through the day at work. There were days I couldn’t get out of bed in the morning.”

Sarah not only started to see her as a patient, she gave Monica a much-longed-for diagnosis. She helped Monica get off narcotic pain medications and helped her seek physical therapy for her joint pain. Today, she says, she’s able to do things she was never able to before.

Sarah’s first patient turned out to be right under her nose. Her medical assistant, Monica Todd, had started having inexplicable health issues as a teen.

“I started to notice joint pain. I started having dislocations,” Monica says. “They told me it was growing pains. It was normal. Everything was fine.” In her 30s, she started looking for specialists to help pinpoint her health issues. “I started getting passed from doctor to doctor. They did testing and they could never figure out what was wrong. Everything looked normal.”

Four years ago, she started — by complete chance — working as Sarah’s medical assistant at Shiloh Family Medicine. “I started telling her about all my symptoms,” Monica says. “It was so bad I could hardly get through the day at work. There were days I couldn’t get out of bed in the morning.”

Sarah not only started to see her as a patient, she gave Monica a much-longed-for diagnosis. She helped Monica get off narcotic pain medications and helped her seek physical therapy for her joint pain. Today, she says, she’s able to do things she was never able to before.

“God absolutely put me in this place so that I could be with her for her to take care of me,” Monica says, adding that in a small way, she’s now able to help care for others with EDS too.

“She has a lot of patients that when I first sit down with them and tell them that I have EDS as well, that I have been dealing with it and that we can help you get better and manage your symptoms, they just break down and start crying,” Monica says.

When asked about the nearest doctor who specializes in Ehlers Danlos, Sarah says she’s pretty much it in a six-state region. She’s working on getting her license in Colorado and Utah so she can help patients there as well.

“I don’t want anyone else to have to sit longer than is necessary with a feeling of – can somebody help me? I remember that feeling of not knowing who to call or who to even ask,” she says. “I don’t want people to feel that way.”

“It hasn’t been clear cut for her,” Naomi says of her mom. “The fighting isn’t easy. It takes a lot for her emotionally to be able to do this. The stories are heavy.”

There are days of sheer exhaustion. Last fall, just before Sarah and Kit went off on a trip to Ireland, she remembers telling her husband, “I am so tired. I don’t know how to keep doing this with just me. He said, ‘I think you need to go on vacation and have a little time. You aren’t going to stop doing this because you know there is someone else out there like we were who don’t have anybody. If you stop, there isn’t anybody else who is going to step in right now.’” Sarah knew every EDS call or email would go unanswered while she was away. With a reflective look, however, she says, “I don’t have a single patient that I can think about and say, I would be OK walking away from being able to provide care for them. I can’t do that.”

Sarah and Kit now have six children — Naomi, 18-year-old Jacob, 16-year-old Jonathan, 13-year-old Teagan, who was adopted after a medical mission trip to Ethiopia in 2010, (Sarah and Kit have taken a handful of these missions over the last 13 years), 10-year-old Faith and 7-year-old Miriam. Over the years, Sarah has learned that it’s not only Naomi with Ehlers Danlos. Miriam and Jacob also have the genetic disorder. For now, their symptoms are manageable.

On occasion, when a patient comes in to see Sarah, she’ll be sporting a periwinkle sweater with an embroidered zebra on the front. The animal is the EDS mascot. As the Ehlers Danlos Society so beautifully puts it, “Medical students have been taught for decades that when you hear hoofbeats behind you, don’t expect to see a zebra.” The takeaway? Those with EDS are the zebra. Each animal has its own unique stripes. No two EDS cases are the same. No one expects to see them.

It's why Sarah has learned never to make assumptions.

“I love complicated problems,” she says. Her husband is quick to add, “She’s tenacious. She’s a tenacious bulldog who listens to her patients.”

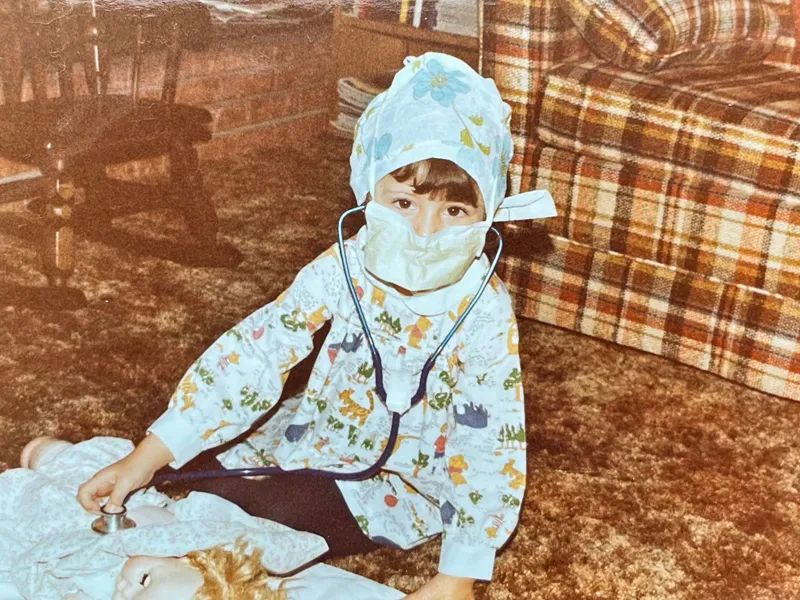

Sarah says she doesn’t remember a time when she didn’t want to be a doctor. She grew up next door to her grandmother, who was a nurse.

“I remember poring over my grandma’s surgical anatomy books, her surgical nursing books and pharmacology books and just thinking it was the best thing ever,” Sarah says. She has a picture of herself dressed in her grandma’s scrubs checking the heart of her baby doll. “It never stops being fascinating to me.”

Her grandma Bobby not only taught her to read using those books, but she was also Sarah’s biggest cheerleader.

“I started out medical school single. I got married between my third and fourth semester of medical school. I had Naomi my third year of medical school and I had Jacob 10 days after I finished my last rotation in my fourth year of medical school,” Sarah says, acknowledging she didn’t follow the conventional route. “The whole time, my grandma was just cheering me on.” Sadly, her grandma died of metastatic breast cancer shortly before Sarah finished her first year of residency.

During those early years of medical school, Sarah sported license plates which read “DOC 2 B.” Some of her peers would look at her, knowing she was married with kids, and would say things like, “You’re probably not going to want to stick with it.” Sarah remembers saying firmly, “Well, I think I might.” She adds, “I couldn’t think about anything else that I could be as passionate about — ever.”

While Sarah would love help in caring for Ehlers Danlos patients, she knows she’s right where she needs to be. While she’d love to create a clinic exclusively for those with Ehlers Danlos, she realizes that, for the most part, these types of clinics are cash-only and don’t accept Medicaid or insurance. She can’t imagine having to say “no” to a large percentage of those who suffer.

She also knows she’s practicing this type of medicine because of a devastating crash that rocked her family’s foundation. That point is never lost on her.

“If the only reason why I went to medical school was so that my daughter could have a life and live again after what happened to us, then it was worth it. All of it was worth it,” Sarah says.

Asked if she’s thankful for her mother’s fighting spirit, Naomi says simply, “More than I can ever say.”

“God rescued me and he rescued my daughter and he rescued my husband, not just for us but for other people and for His glory,” Sarah says. “I’m not going to stop saying thank you for that. I’m not going to be quiet about that. It’s such a beautiful gift.”

HOW MANY PEOPLE ARE IMPACTED BY EHLERS DANLOS?

There are 14 types of Ehlers Danlos Syndrome. Hypermobile EDS can impact one in every 3,000 people and accounts for roughly 90 percent of all EDS cases. There are other rarer forms that account for one in every 1 million people.

TO LEARN MORE about Ehlers Danlos Syndrome, visit the Ehlers Danlos Society at ehlers-danlos.com.