The Long Road Home

Abby Hinthorne creates a life with hard work & love at the center

During her senior year of college, Abby Hinthorne had an assignment to depict her life in art. When it was her turn, the lights dimmed and a recording of her home church singing hymns in German began.

A spotlight illuminated a figure in the center of the stage. The light began at the base of the figure, inching up slowly, showing the floor-length cotton skirt, modest long-sleeve blouse covered with a cotton apron, then stopping on the head of the faceless mannequin. As the music faded, Abby stepped out from behind the mannequin and began telling her story, the life of a young Hutterite woman. It was a story none of her fellow classmates had heard before.

Abby was raised on the Ayers Hutterite Colony near Grass Range, Montana. Her father was the colony’s manager. She was the ninth of 10 children and, with her siblings, attended a one-room school through the eighth grade. As a member of the colony, all her needs were provided: food, shelter, clothing and education. But, as a young teen, Abby yearned for more.

“I had it in my mind that I wanted to get away,” she says, “I wanted the freedom.” She received her GED, a high school equivalency certificate, in nearby Lewistown and worked for several years, saving money, as a nanny. By the time she was 23, she felt ready. “I remember telling my mom, I just want to move to Billings and wear jeans!”

Leaving the colony isn’t easy.

“There is no financial assistance to help you succeed,” Abby says. “But there was no way I was going to allow myself to fail and return.” Though her parents supported her decision, it was hard for many members of the colony to come to grips with her choice.

She left with the clothes on her back and some cast-off clothing from the woman she’d worked for as a nanny. “It wasn’t much,” Abby says, “but then I had no sense of fashion anyway!” She moved in with a friend that the woman knew and started her life in Billings.

“The entire world was foreign to me,” she says. “It was complete culture shock. I remember laying in my bed that first night, hearing cars and sirens. It was so noisy. All I could think was, will I survive?”

Abby did more than survive. She made friends, joined a church, bought a car and put herself though college. And she wore jeans. She maintained a close relationship with her parents until their deaths and, to this day, still visits relatives and friends at the colony.

“Mom was always there for me,” she says. “She was such a nurturer and cared so deeply. She was a very spiritual person and always connected with others. She was kind and wise and she loved people well.”

Her father never quite understood Abby’s desire for independence. When Abby graduated, her parents attended the ceremony. Sitting with them was Abby’s future husband, Tom Hinthorne. As the graduating seniors came into the auditorium, her father asked Tom, “So this is a really big deal?” Tom answered “Yes, it is.” To which her father said proudly, “And she did it all on her own.”

“He didn’t understand me,” she says, “but I think he admired me.”

Sometime later, when she was managing a local restaurant, McCormick Cafe, her father said to her, “I’ll be damned, they got you managing it?”

“It’s not that he thought I couldn’t do it,” she says. “It was more a surprise that someone would give me, a woman, the opportunity.”

Back in college, the faceless mannequin was Abby’s way of depicting the lack of individuality of Hutterite women. “I never felt like an individual there,” she says. “We all looked the same, dressed the same and did the same things. I craved more. God gave me free will for a reason.”

By the end of 2000, Abby had married Tom. They had plans for a family and dreams of a flourishing catering business. But across town, in a world removed from the Hinthornes, a baby had been born who would one day have a profound impact on their lives.

A young, unwed teenage mother was halfway through her pregnancy when an ultrasound revealed that her baby would be born with severe birth defects. The doctors advised abortion. The young mother held fast and delivered a baby girl.

Her daughter, whom she named Keyara but soon began calling Kiki, was born with spina bifida, a defect of the spinal cord and caudal regression in which the lower part of the spine fails to develop correctly. In her case, the lumbar and sacrum didn’t properly develop. Her vertebrae stopped growing at the T-12, which is roughly two-thirds of the way down a normally developed spine. Kiki was born with unusable legs, which were clubbed and crossed. The battle that had begun in the womb would continue for the rest of her life.

In the next five years, her mother gave birth to three more girls, all before she reached the age of 20.

In those same five years, Abby and Tom launched Abby’s Catering and were working overtime to make it a success. They brought their only child, Kendahl, into the world. Life began to have a rhythm.

Kiki knew at a very young age that she was “different.” She learned to scoot across the floor using her hands to lift and move her body. Her home life wasn’t healthy. She and her sisters endured abuse and neglect and were exposed to drugs. It wasn’t long before they were removed, and foster care became a way of life. Kiki was just 6 years old.

For the next decade, she would cycle through foster home after foster home, sometimes with her sisters, sometimes alone. Several times she was placed with relatives, but always, she was abused, neglected, removed, kicked out or asked to leave. Her heart became guarded, her trust disappeared, her identity was lost.

“With my disability, there are always other health issues too,” Kiki says. “I’m susceptible to UTI’s (urinary tract infections) and I remember hurting so bad and knew I needed a doctor, but I wasn’t getting the care.”

School was always difficult. She felt alone and rejected most of the time. “I get that children are scared and confused of someone who’s different,” she says. “I might have been able to handle that, but the bullying. Well, that was tough. It still is.”

At one point, the decision was made to amputate her legs in the hope that she would be more mobile. She was left with two stubs and used a wheelchair to get around.

By 10, she was adopted by a Billings couple who also neglected and abused her. “The abuse started as soon as I was ‘theirs,’” Kiki says. By junior high, she had endured so much emotional and physical pain, she lost hope.

“I was depressed,” she says quietly. “I had no support system. My body was covered with bruises and cuts. Suicide seemed the only option for me.”

While her parents were out of the house, Kiki tried to take her life. They came home just in time to save her. But instead of comfort, they were filled with anger and she received their wrath.

“I spent my days terrified of them,” she continues. “I didn’t want to be at school, but I didn’t want to be at home either.”

Several teachers at her junior high suspected abuse and though Kiki denied anything was wrong, they made a call to the authorities. Kiki was removed from her adopted parents’ home that day.

Meanwhile, at the Hinthorne home, Kendahl was a thriving 12-year-old. Tom and Abby were active and busy with their lives. But things would soon change. Perhaps it was a deeply embedded love for others that Abby claims her mother taught her, perhaps it was an awareness of a need and the inability to ignore it. Or, perhaps, as Abby would say, “It was God’s timing.” But Abby and Tom found themselves unable to ignore the need for foster parents in Billings.

“We started hearing news about the horrors of kids in the foster system,” Abby says. “We kept hearing things and getting angry about it. But what does anger do? Nothing. If we wanted to help, we had to do something.”

The Hinthornes trained to become emergency foster parents, willing to be available for those times when a child needs an immediate place to stay.

After Kiki was removed from her adoptive home, a relative stepped in to care for her, but after eight months, she was told to leave. Social workers with the state Child and Family Services Division called Abby and Tom. After 10 years of moving from house to house, Kiki needed an emergency home.

“I was told that a young girl, 14, needs a place to stay,” Abby says. “She would be with us until something permanent came along. We found out that not only was Kiki in a wheelchair, but she had been severely abused physically and emotionally and we were her seventh placement. We were terrified we wouldn’t be able to meet her needs. All we could do was trust God that we were doing the right thing.”

Kiki arrived at the Hinthornes with all her possessions in two garbage bags, and a list of medical issues.

“We knew immediately that we wanted to be Kiki’s permanent home,” Abby says. “We couldn’t see this child going through any more trauma. In the first six weeks, we had 20 doctor appointments and an emergency surgery. Her physical health had been so neglected.”

On the day of the first visit, they sat with Kiki and Kendahl and talked about expectations. “We didn’t have many,” Abby says. “We just really wanted her to know that even if she was handicapped and she’d had an unimaginably tough life, that we had expectations. We go to church. We help each other out. We treat each other as family, and she was safe with us.”

Though the Hinthornes were all in with Kiki, the transition was difficult. As more of Kiki’s history was unveiled, Abby knew it would be a long road to their new normal. It was difficult for Kiki to believe the Hinthornes wouldn’t cast her off.

“I didn’t believe them,” Kiki says. “Why should I? I’d been promised love and homes and security from so many people and all of them failed me. Why would it be any different here?”

“It was hard,” Abby says. “I was a nurturing mother to Kendahl. We always had a close relationship and I thought, ‘I’m good at this,’ but it wasn’t working. It was devastating. It seemed the harder I tried, the more she pushed me away. All of us.”

“I was a brat,” Kiki says. “But I was scared. I didn’t want to give them my heart because I knew that it’d just get broken again.”

Desperate to find help, Abby met with doctors and therapists, hoping to find someone to make it possible for her help Kiki and at the same time make sure she still had a great relationship with Kendahl. The sacrifice and stress on each family member proved to be difficult.

One of the most helpful was Dr. Brenda Roche, Ph.D., who specializes in neuropsychology and has 30 years of experience with children in the foster system.

“Kiki had undergone so much trauma in her life,” Roche says. “She was reacting from a self-preservation perspective. She had no idea what a healthy mother looked like, or what her role as daughter looked like. It had never been modeled for her. Like many foster parents, Abby thought love would be enough. But it isn’t with these kids. They’ve been through too much to trust.”

Once Roche began to help Abby and Kiki understand what each of them needed and why they were responding the way that they were, it helped them to bond.

“I had Kiki think about the things she liked and disliked about the mother figures in her life and what she wanted or hoped a mother would be to her,” Roche says, “and she came up with: someone to love her no matter what, who set limits and taught responsibility. Someone that would care for her, spend time with her, appreciate her and would treat her as abled, not disabled.”

“Her list was pretty impressive for someone who had never had those things before,” Roche says. “It was obvious to me that she had watched Abby and Kendahl’s relationship and wanted the same thing for herself. She was just afraid to hope for that.”

Over the next few years, the Hinthornes took small steps to help Kiki find her individuality and blossom. Before long, she began calling Abby and Tom “Mom and Dad.”

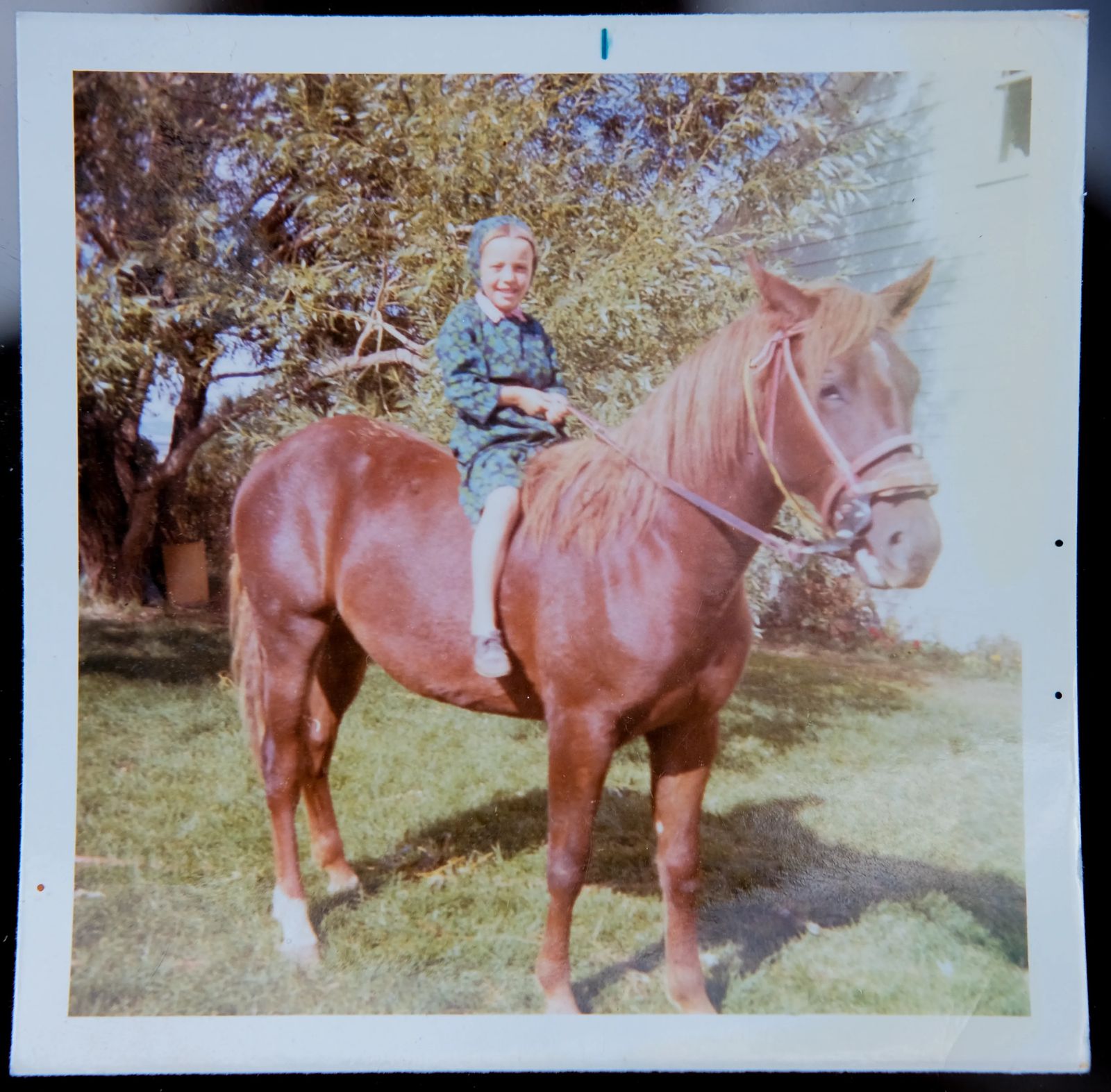

She started high school, made friends and experienced some firsts — birthday parties, camping, skiing, four-wheeling and boat rides. She learned to cook and helped with the catering business. She went with the family to Cat-Griz games, Disney World and Hawaii. She lay on the beach and felt the ocean. She took driving lessons and now owns a car. An early love for horses was nurtured and turned into a love and talent with horses so strong that she earned a scholarship at Rocky Mountain College in equine therapy.

What lay dormant in her heart was allowed to wake up. “It’s been amazing watching her blossom in our family. She has a deadly sense of humor,” Abby says, laughing. “She loves to make us laugh by poking fun at herself or one of us. One time she said she was glad for the money she’s saved over the years in shoes.”

Today Kiki is finishing up her freshman year of college online and living in her first apartment. She had planned to spend the summer traveling with FosterClub, a motivational touring group that educates communities about foster care and uses youth that have successfully transitioned into young adulthood as examples and speakers. With the novel coronavirus, those plans are now on hold.

Kendahl is a junior and spent spring, like all the students in Billings, schooling from home. She’s already looking forward to the journey into college.

Abby loves teaching both girls how to navigate life, and how to find their individual gifts.

All three women, when asked what this experience has taught them, agreed that the main theme has been compassion.

“No one knows the road you’ve been on,” Abby says. “You just never know what’s behind a person. Take time to get to know them before you harshly judge.”