Backing the Blue

Wife of injured Billings police officer takes fight for injured officers to our nation’s capital

The silvery scars that run up and down Ladd Paulson’s legs serve as a faint reminder of the not one but two near-fatal motorcycle crashes he suffered while on the job as a Billings police officer.

The first happened in 2002 while he was on his police motorcycle following up on suspicious activity. Even with his lights on and siren blaring, a car T-boned him at 50 miles an hour. The impact threw him into a nearby ditch and caused a brain injury, broken ribs, a fractured skull and kidney, a crushed leg, collapsed lung, perforated diaphragm and — the most critical — a transected aorta.

“His insides were scrambled,” says his wife, Heidi Paulson. “He should never have lived. He shouldn’t even have made it to the hospital.”

Just three years later, after a grueling recovery, Ladd would mount his police motorcycle again as a training officer. He was on his way to test the last officer hoping to become certified for the motorcycle patrol when a minivan turned in front of him as he was traveling down Airport Road at 60 miles an hour. There was no shoulder to the right of the road and an oncoming vehicle prevented him from swerving out of the way. His shoulder and helmet became trapped in the vehicle’s frame and with the impact, all the nerves that ran down his right arm were pulled from the base of his spinal cord. The injury, a brachial plexus avulsion, delivers constant and debilitating nerve pain daily.

“The way he describes it,” Heidi says, “it’s like putting your arm in a deep fat fryer. He says it is as if there are tiny people with pickaxes on the inside of his bone, trying to chop their way out while it’s on fire. It is intense, intense pain.”

While Heidi tried to help Ladd pick up the pieces, she remembers the chaos, confusion and heartache she endured watching her husband heal from trauma not once, but twice.

“There are times when you just pull out your hair and want to scream,” Heidi says. “It’s just too much. You tell yourself, ‘I can’t do this.’ But, it’s one day at a time.”

Now, nearly 14 years after his last accident, the Paulsons have settled into their new normal. Aside from spoiling grandkids and Heidi’s work as a partner in a software company, she spends time juggling calls to Washington, D.C., researching legislation and serving on a few nonprofit boards designed to fight for what she calls “the veterans of the wars on our streets,” our forgotten heroes in blue.

“Here you are in Billings, Montana, working a computer and a phone, trying to impact the lives of law enforcement all over the U.S. and Canada,” she says.

After Ladd suffered his wrecks, Heidi quickly discovered that when it comes to helping an injured law enforcement officer, the system was broken.

“When an officer is killed in the line of duty, there are lots of organizations that reach out to the families of those officers, which is important,” Heidi says. “But, when a police officer is critically injured serving in our local communities, there really was nothing.” She adds that many local police departments don’t even have a protocol on how to care for an injured officer.

“What do we do next? How long does insurance go?” she says. “The state of Montana doesn’t even really understand the tax status of disability pensions, still.”

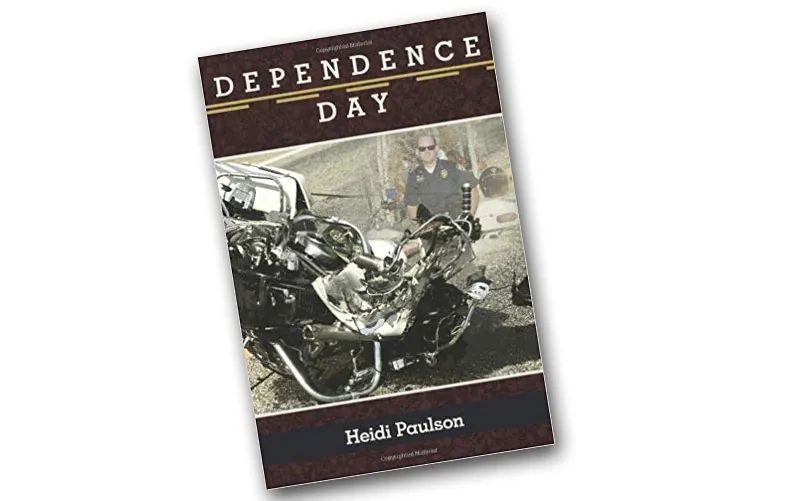

In 2010, Heidi wrote a book titled “Dependence Day,” chronicling her and Ladd’s journey and the strength they found in their faith. The book attracted attention from other families of critically injured officers. It’s since opened doors.

“A guy from Missouri read my book and he was just starting an organization starting hunting trips for officers injured in the line of duty through Hunting for Heroes,” Heidi says. “He wanted to pick my brain and talk about what it was like to be the spouse of an officer and what support, or lack of support, we had.”

The trip underscored what Heidi already knew. There really wasn’t a support network.

“There are more people around the country who are falling into this chasm,” Heidi says. She used to think that she felt alone because she lived in a rural state. “But in meeting these people from around the country, it’s not because we are from Montana. This gap exists everywhere. That really brought that to light.”

When she returned home, she started a private Facebook group called Veterans of the War on our Streets (VOWS) to help families connect. By word of mouth alone, the page took off.

“By forming that group, we really learned about each other’s problems. Everybody’s story is just heart-wrenching,” Heidi says. She shares the story of the officer injured in a bomb blast who suffered a brain injury and the officer who suffered intense post-traumatic stress after working in a human sex trafficking unit. Heidi adds, “There was an officer working in a rural part of Georgia, he was driving on a two-lane highway and a person texting crossed the center line and hit him head-on. He was badly injured and was still going through surgeries. He wasn’t able to go back to work within a year and he was fired.” She says the officer had served for more than 20 years on the department.

“There are things that you just can’t comprehend that really do happen out there,” Heidi says. “We now have more than 300 members who are injured law enforcement and their spouses in our group,” Heidi says. The mission is to nurture families, provide resources and provide a support system for injured officers and their families. Heidi adds, “By having that group, now we felt like we had the power of a voice.”

As the Paulsons tried to figure out how this group could use that voice, they created and have now hosted what’s called the VOWS retreat for injured law enforcement and their spouses. They decided Montana would be a beautiful backdrop to help these couples heal. They knew firsthand that after an officer is injured, divorce rates increase, PTSD and brain injuries become day-to-day challenges and worst yet, thoughts of suicide are a real threat.

“All of the officers we’ve worked with have gone through the scenario, ‘If I had just been killed, my family would be better off,’” Heidi says. “We’ve been to that point. So, I get it when someone says, I don’t know what to do, he’s depressed. After an injury, you aren’t the same person and neither is your spouse because of the experience,” Heidi says, noting the importance of retreats like this. “They really need someone reaching into their lives to say, ‘Here are some tools to work on. You need to fall in love again with this new person.’”

In 2018, the number of police officers who died by suicide was more than triple that of officers killed in the line of duty. Source: Ruderman Family Foundation

Since the first retreat in 2014, they’ve hosted 26 couples. Nine more will make their way here this summer.

“The opportunity to speak hope into the lives of our fellow law enforcement families who are hurting and feeling defeating and alone — to give them hope — is a really big deal,” Heidi says.

During the retreat, the officers flyfish, ride horses and just soak in the beautiful landscape near Belfry. During one of their visits, a Highway Patrol Officer from South Carolina made the trip with his wife. At the time of his injury, he had been working the scene of an accident when a car rammed into his patrol car at 70 mph. The officer suffered a severe traumatic brain injury. When the couple came to the VOWS retreat, they were four years into recovery.

“He hadn’t spoken more than a couple of words in four years,” Heidi says. But in the remote campsite with fellow injured officers by his side, Heidi adds, “We were all laughing about not being able to remember stuff and all of a sudden, this guy just starts talking. His wife’s eyes got as big as saucers. She hadn’t heard him speak a sentence in four years and he just starts sharing and talking. It was absolutely amazing.”

It was through those experiences that Heidi started to realize that these connections could be used to make an even bigger impact on the lives of injured officers. She realized the widespread problems behind the lack of disability insurance available to an officer. She learned, for instance, that when Social Security was established, law enforcement agencies and railroad companies were given the chance by the federal government to opt out since both had long-established pension plans. Many law enforcement agencies did opt out.

“What that means is, if an officer is injured in the line of duty, they don’t qualify for Social Security Disability Insurance. Most officers aren’t aware they don’t qualify,” she says. On top of that, private disability insurance is hard to come by for an officer.

“We tried to get Ladd personal disability insurance before he got hurt,” she says. “He was turned down by four insurance companies because of the high-risk nature of the job. You have to at least make sure they are aware and provide a way to make sure they can get coverage.”

In 2017, she started to tackle the issue of disability pensions. She says right now they are exempt from federal withholding before retirement. The problem is, when the officer turns 65, the pension reverts to a retirement pension. “All of a sudden it becomes taxable,” Heidi says. “It’s not as if their disabilities go away.”

She traveled to Washington, D.C., in the spring of 2017 to try to encourage lawmakers to make disability pensions tax-exempt for life.

“We got the ball rolling and (Montana) Senator (Steve) Daines said, ‘Yes, I will sponsor this. Let’s get this going.’ Congressman Norman from South Carolina told us absolutely, he was on board,” Heidi says. “By the time we got to D.C. in May of last year, we actually had bill language and walked it onto the Senate and House floors. We actually got to walk down there with them to turn the bills in, which was really cool.”

Sadly, the Putting First Responders First Bill died in the Finance Committee. Heidi is hoping a visit to D.C. this year for Law Enforcement Memorial Week will revive efforts to get the bill passed.

There will likely be additional trips to the capital now that she’s added a new title to her long list of volunteer efforts. In addition to serving as vice president for the wounded officer's division on the non-profit support group known as How 2 Love Your Cop and serving as the legislative liaison for a non-profit advocacy group known as The Wounded Blue, Heidi was asked to serve on the Department of Justice Public Safety Officers’ Benefits Stakeholders Group. This group oversees the program that provides death and education benefits to not only the survivors of fallen first responders but disability benefits to officers catastrophically injured in the line of duty. It’s a program that has been criticized in the past for taking years to process claims, leaving officers and other first responders waiting for critical help. Heidi will now be a voice for disabled officers and their families.

“If someone told me 10 years ago that I would be talking to senators and congressmen and making trips back and forth to D.C. to sit on a Department of Justice committee to help administer benefits to injured law enforcement, I’d say no way,” Heidi says. “That’s not something I had on my bucket list or a place that I thought I would be headed in my life.”

But, even so, many days she still picks up the phone to make that call. “I will often say, ‘Hi, you don’t know me, this is Heidi from Montana.”

As she talks about how far she and Ladd have come over the last 17 years, she starts to shuffle the blue plastic bracelets that sit on her wrist.

“They remind me to pray for those critically injured officers,” she says. She always keeps her husband on that list.

“God sees the big picture. He saved Ladd for a reason,” Heidi says. “He should not have survived either one of those accidents. There’s a bigger purpose and we may never know exactly what that purpose is.”

Ladd Paulson doesn’t have the answer to that question either but he takes great solace in the fact that his wife is on the front lines, fighting for injured officers just like him.

“A lot of this bad stuff that we’ve been exposed to has been able to be turned into something good,” he says as he looks at his wife. “We just had our 33rd wedding anniversary and I love her more all the time. It’s amazing how she’s stepped up and done things that others would have cowered from. I’m humbled because I don’t know if I could have done it.”

“Being able to see that we can make a difference for those who come after us?” Heidi says, “That’s what keeps you going.”

HELP OUR WOUNDED BLUE

Ways you can bridge the gap for injured law enforcement

* Support programs like The Wounded Blue, which provides support, resources and legislative advocacy on behalf of critically injured first responders. Visit thewoundedblue.org

*Watch “The Wounded Blue,” a documentary that shares the stories of six police officers who inspired the creation of The Wounded Blue Foundation. Proceeds from the film go to wounded officer outreach.

* Support active- duty and wounded law enforcement families, including VOWS retreat attendees, by visiting how2loveyourcop.com

*Follow Dependence Day on Facebook for information about current legislative efforts and positive law enforcement stories.