Disease Detectives

Contact tracers work to follow COVID-19’s every move

Kim Bailey and Hannah Tougas will never forget standing in a man’s garage protected from head to toe donning gloves, N95 face masks, gowns and goggles, with swabs in hand ready to perform a test for the first suspected case of COVID-19 in Yellowstone County. It was the first week of February.

“We brought him out to the garage because there were other family members in the home,” says Bailey, a registered nurse and the communicable disease program manager with RiverStone Health. Tougas, also a registered nurse in the program, is Bailey’s right hand in these investigations. “We couldn’t open the door,” she says, because they didn’t want to give any virus a chance to escape.

The man being tested had just come back from China and the duo was monitoring him, checking in daily and asking if he had any signs or symptoms of the virus.

“He developed symptoms,” Bailey says. “So, Hannah and I went out. That was the first test we did on a person. It turned out that he didn’t have that but another viral illness.”

Not only did Tougas and Bailey test potential COVID-19 positive cases early on; more importantly, they were responsible for retracing every move of those who tested positive to try to stop the virus from spreading.

“The whole thing is being a detective,” Tougas says. “It’s not just COVID. It is every communicable disease that gets reported.”

They are given a name, birthdate, a contact number and where the person was tested. With those very basic details, the two get to work. Tougas says they would ask, “What is the story around this person? If they were picked up by an ambulance, was the ambulance crew wearing personal protective equipment?”

The pair looks at people the positive person had close contact with 48 hours before the person showed symptoms. Recall during that window of time, Tougas says, is usually pretty good. It’s tracing a person’s steps back two weeks that can get tricky. The investigation has to travel that far back in hopes of finding out how a person was exposed. Tougas says, “That gets a little more difficult.”

“Across the board, the people that have tested positive, they don’t want to have given this to anyone else,” Bailey says. “They are very open and honest about where they’ve been and the people they’ve been around.”

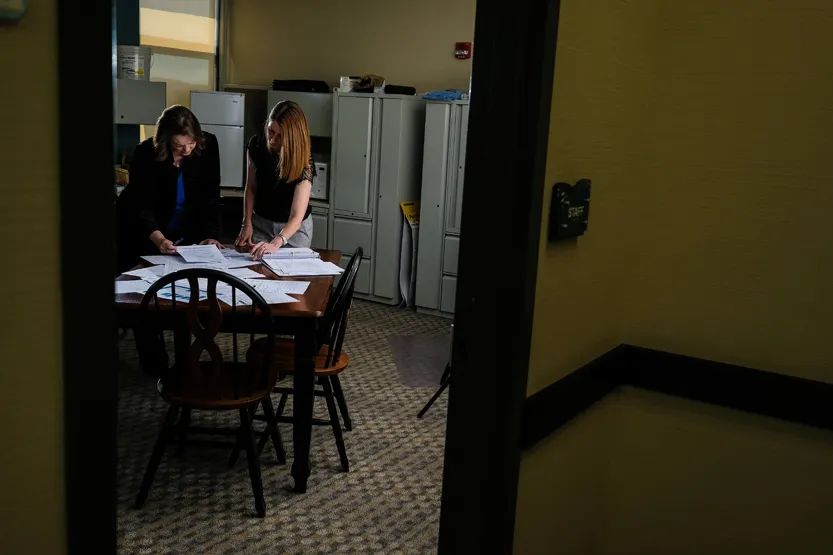

On this day, laid out on Bailey’ desk is a handful of charts full of circles and arrows, each one details a cluster of COVID infections they’ve investigated and the positive cases that resulted. One shows an outbreak tied to a birthday party, another details a handful of cases at a local grocery store, and a third showcases the links of infection from a carpool.

“OK, let’s start to identify how these people are connected,” Bailey says. “Within this group, these people were not connected to this person, but this person was the common link,” she says pointing to the one case that didn’t test positive but seemed to be the bridge between two clusters of infection. “Who tests positive? Who doesn’t? Who’s symptomatic? Who isn’t? The whole thing is baffling. It is hard to wrap your mind around it.”

For each investigation, there might be as few as two people to question who had contact with a COVID-positive person, or as many as 20.

By 11 a.m., right before sitting down to talk about her job, Tougas had already taken 10 calls tied to her investigative work. “It’s never ending,” she says.

Before the pandemic, Tougas and Bailey spent their days tracing outbreaks tied to sexually transmitted diseases. Recently, they had a cluster of Hepatitis A cases. They chart food-borne illnesses and are the first line of defense in cases of whooping cough or the measles.

When a pandemic breaks out, they can’t just put everything aside to focus on the threat. They are required by law to follow up on every kind of communicable disease or illness that poses a threat to the community’s health.

“In the beginning, it was mass chaos,” Bailey says. “There were a few weeks there when we were getting 20 cases a week.”

They expanded their investigative team, pulling from all areas of RiverStone Health. At its height, they had a team of 14 people.

Bailey and Tougas have had a hand in investigating all 100-plus cases in Yellowstone County, plus those cases that might have crossed into our community from nearby areas. That equated to more than 400 individual investigative calls. They said deep breaths and delegating kept them sane.

“We were triaging people on the phone, letting them know that they needed to stay home if they weren’t sick enough to normally go to their doctor,” Bailey says. “We didn’t want to overwhelm the hospitals. That was a big piece of it.”

While the job was stressful, Bailey says the one scenario that kept her up at night was the thought that a case could erupt into an outbreak at a nursing home or assisted-living facility.

“If there is a positive case, you have to jump on it fast because in those facilities, it will spread like wildfire and those people will die,” Bailey says, adding that in many of those facilities, the elderly need contact with others just to get fed and dressed. “That’s the scariest thing. I know those facilities are trying like crazy to protect their people.”

By mid-June, the COVID-19 death toll stood at three. For Bailey and Tougas, each casualty was personal. Colleagues say when the news came, the pair looked as though they were grieving the loss of a loved one.

“It hit me really hard,” Tougas says. “It brings tears to my eyes even now.” Bailey adds, “We had contact with these people, interactions with their family.”

“We talked to all of them on the phone,” Tougas says. “They were just living their life and doing things like they normally would and then, they found out they had the virus.”

“In some people, it just has this cascade effect in their body and their immune system just reacts causing their vital organs to fail,” Bailey says. “It’s just an overreaction of their immune system.”

With the future unclear about a potential second wave of the virus, Bailey and Tougas are using the time to continually tweak their next plan of attack.

“We just re-evaluated our team of people to make sure that they are going to be ready if we start to have an uptick of cases,” Bailey says. “We have to keep people at the ready.”