Do As I say, Not as I Did

My experience with Basal Cell Carcinoma

By Virginia Bryan

Before the Covid-19 lockdown of 2020, my primary care doctor recommended that I have a full body skin exam. It had been several years since the last one. I didn’t tell her about the odd spot on my nose that bled periodically. It would heal, but sooner or later, it opened again. Now in my late 60s, I have several skin cancer risk factors: fair-skinned, blonde, a history of sunburns and of northern European descent. My gut said my primary care doctor was probably right.

I scheduled a skin exam, but when the time came, I didn’t feel well and I canceled. By then, Covid was in full bloom. It seemed prudent at the time. Did I mention that my husband and I sold our house, downsized and moved during this period? One day, while hanging a metal sign on our new deck, a weak board gave way and I went straight through. That laid me up for a while. In August 2020, my grandson was born. My life felt upended and I never got around to rescheduling my exam.

As summer turned to fall in 2021, that spot on my nose opened up again. This time, it was a hole about the size of a juice box straw. Oddly, it didn’t bleed.

“This doesn’t look good,” I remember thinking. When I learned that Billings Clinic Dermatology sets aside two days a week for walk-in patients, I called.

HOW BAD COULD IT BE?

Billings Clinic dermatologist Michele Spenny, M.D., peered closely at the spot on my nose. “That’s coming off,” she said. In her notes, she identified the spot as a basal cell carcinoma. The next day, a biopsy confirmed it.

I took the literature Dr. Spenny provided, went home and waited. As a teenager, a benign lump was removed from a lymph gland on my neck. Near age 40, a benign lump was removed from my thyroid. The scars on my neck are hardly noticeable. Cancer wasn’t a family risk factor. How bad could it be?

Shortly after my visit with Spenny, I was scheduled to see Dr. Mark Jones, one of two fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons/pathologists at Billings Clinic. Scott Monson, one of Jones’ three Mohs technicians, greeted me upon arrival. His calm, friendly demeanor was reassuring. Monson said he’s pretty good at reading people. He remembered I seemed nervous.

I settled into a chaise-like chair in the Mohs surgery room. There were bright lights overhead. My anxiety levels were rising. Monson eased me into the procedure by cleansing, sterilizing and covering my face and neck. He handed me a metal plate about the size of a hardback novel. When I let go of it during the surgery, Jones got a bit excited. Later, he told me it was an electric ground for the cautery tools he uses. Keeping my hands busy and out of his way was a secondary benefit.

Each Year, more than 5 million skin cancers are diagnosed in the U.S.

Like Monson, Jones was affable and exceedingly patient. After 20 years of working together, these two men can communicate without speaking. They find that engaging patients in conversation puts them at ease, and relaxed patients have better outcomes. Jones outlined what I could expect in the Mohs procedure. First, he’d numb my nose and cheek. I must have gasped audibly upon seeing the needle. Scott encouraged me to press hard on the metal plate. It was white-knuckle time.

“I hope that’s the worst of it,” I said to myself after the last pre-op lidocaine injection. I took a deep breath and waited for it to take effect.

BE CAREFUL WHAT YOU ASK FOR

Jones proceeded to remove the first layer of thin tissue where the carcinoma was located. In an adjacent lab, Jessica Hart, another of Jones’ Mohs technicians, received the removed tissue, froze it and prepared it for examination under a microscope. She has 15 years’ experience working with Jones. If any cancerous tissue was observed, Jones would remove another thin tissue layer until the remaining cells were cancer-free.

As Monson and I waited in the surgical room, I wondered aloud if I might get a “nose job” while I was there. I’ve always been self-conscious about my nose. Monson chuckled, but I sensed he didn’t think it was funny. “Be careful what you ask for,” he gently cautioned.

After two more extractions, Jones was satisfied that all of the cancer was removed. I was feeling no pain, but my curiosity was growing. Jones handed me a small mirror. “Do you want to see what your nose looks like?” he asked.

“Holy shi**!” I exclaimed. I was shocked to see a round, gaping hole on the right side of my nose. It was big enough to hold the tip of my little finger. Monson’s cautionary words echoed in my head. If I’d waited any longer, the cancer cells might have extended to the inside nasal wall or worse.

Jones gave me a few minutes to regain my composure. One option was to leave the hole as it was and allow it to heal. Or, I could undergo a “nasolabial transposition flap closure” in which tissue and skin from my right cheek would be removed and used to fill and cover the hole.

“Do what you can,” I said. “We can’t leave it like that!” I hope I didn’t shriek. By then, the seriousness of what I’d just been through was apparent.

Earlier, Monson had assured me that Jones was an excellent surgeon. “The guy’s an artist,” he said. Of course, I paid little heed when he said it, but I remembered his words and tried, once again, to focus on my breathing. My nose and face were prepared for reconstruction and I got another shot of lidocaine. I felt completely powerless.

FOLLOW YOUR DOCTOR’S ADVICE

Near the end of the reconstruction, I could feel a needle and thread being woven through my cheek and nose. The stitches extended along a facial crease (dare I call it a wrinkle?) from my right nostril to my upper lip. To sustain blood flow, Jones connected a blood vessel from the repair site to the extraction site and covered it with gauze. Replacement tissue filled the hole where the cancer was removed. The small circle of skin covering the replacement tissue was attached to my nose with perfectly formed, tiny blanket stitches.

When it was over, I was almost giddy. I told Scott that Jones could win a blue ribbon at Montana Fair for his embroidery skills. I left Billings Clinic with instructions to call Jones’ cell phone with any complications. Thankfully, my Covid mask disguised the large bandage on the right side of my face.

The next day, I returned for a 24-hour wound check. Hart and Jones were delighted with the wound’s appearance. I thought I looked like a pirate. The first few post-surgery days were rough. Prescribed pain medications and regular ice packs dulled the significant facial pain. I tried not to panic when bruising, nausea and nighttime bleeding occurred. I read and re-read the wound instructions and took to heart Jones’ instructions to take it easy for a few days.

By Thanksgiving 2021, I wasn’t wearing a bandage at home. The first set of stitches had come out on schedule. In early December, a second procedure removed the skin flap, leaving me with a small, button-sized scar where the hole had once been. At each check-up, notes confirm excellent healing. In early January 2022, a full body skin exam (recommended by my primary care doctor two years earlier) uncovered no additional issues. By Valentine’s Day, I was released from further care.

As I write this, it’s been nearly eight months since Spenny’s diagnosis. My face is healing nicely. The incision from my nose to my mouth is barely discernible. The button sized scar is also healing, but it needs more time. You won’t see it unless I point it out to you. Jones said it meets his “conversational distance” standard and he’s quite pleased. I am just glad I still have my nose.

WHAT IS MOHS SURGERY?

In the 1930s, Dr. Frederic Mohs, looking for ways to treat skin cancer for patients in his Wisconsin dermatology practice, began applying techniques he learned as a medical school research assistant. In the medical school lab, he learned how to extract and color-code thin tissue layers removed from cancerous skin and how to map out the cancerous and healthy cells. Using this information and the skills he’d learned, Mohs was able to locate and remove skin cancers like mine.

It was a multi-day process back then, primarily because removed tissue had to be coated with a zinc chloride paste and allowed to sit overnight before it could be examined. In contrast, my entire procedure, which involved removing three skin layers, took less than four hours.

Mohs’ techniques have been refined over subsequent decades by Mohs and others, but the two original components—removal of tissue in thin layers and mapping cancerous and non-cancerous cells—remain constants. Hence, the methodology bears Mohs’ name. Now a surgical specialty, Mohs surgery and standards are governed by the American College of Mohs Micrographic Surgery and Cutaneous Oncology, although it’s called “Mohs” or “Mohs Surgery” for short.

Mohs surgery is considered the “gold standard in cancer treatment” according to the Mohs College (www.mohscollege.org). That reputation is earned by its ability to identify and extract damaged tissue, spare healthy tissue, remove the smallest amount of skin possible and achieve the maximum post-surgery aesthetic benefit.

DO’S AND DON’TS FOR SKIN PROTECTION

- DON’T ignore a spot that bleeds or won’t heal. If you have a spot that fits this description and it lasts longer than two weeks, Dr. Jones recommends you have it examined by a doctor. Early treatment eliminates and/or minimizes later problems.

- DO keep your children protected from the sun. Eighty percent of all skin damage occurs before age 18. Apply SPF50 sunscreen liberally and frequently to the arms, legs, neck and face of your little ones. They should wear a hat when in the sun. You weren’t invincible as a youngster and your children aren’t either.

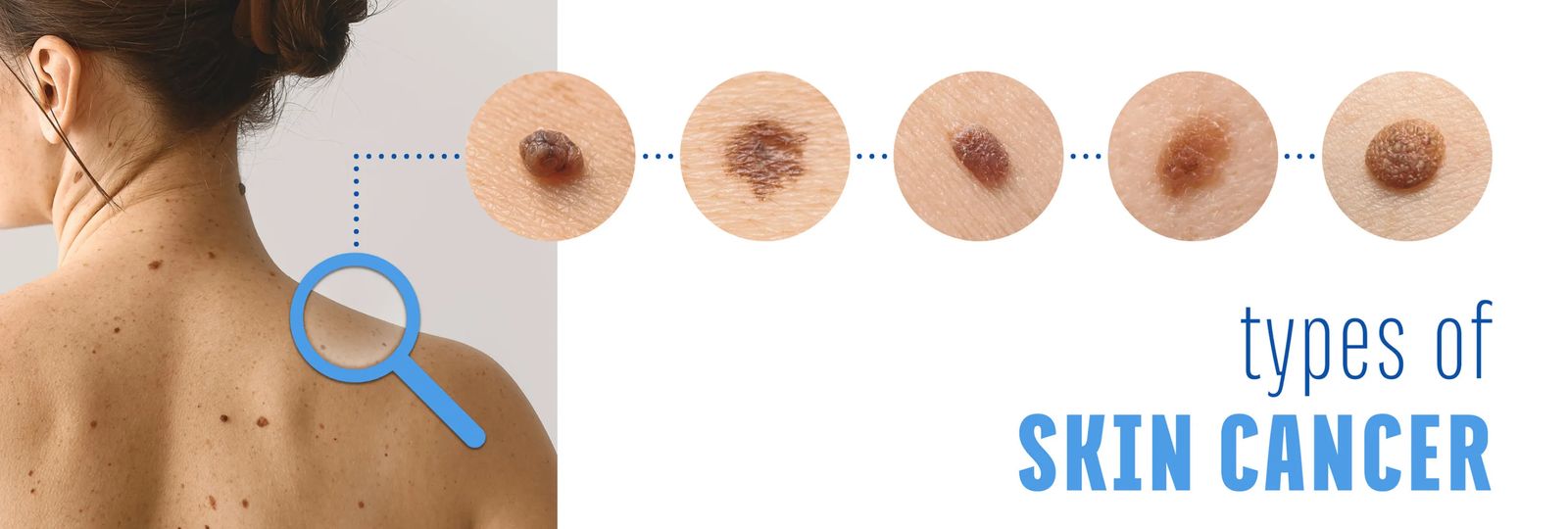

SIGNS & SYMPTOMS OF SKIN CANCER

- Asymmetry

- Uneven borders

- Color variation

- Size greater than 6 mm

- Evolving in size, shape and color