Hard Time & Hard Truths

Willy Johnson uses his past to transform others through faith-based prison program

The video clip plays. A 19-year-old boy sitting in a maximum-security youth detention facility looks toward the camera and, with a somber look, talks about the day that changed the trajectory of his life. July 29, 1994. It was the day he drove into a South Salem, Oregon, parking lot, pointed a sawed-off shotgun through the window of his car and opened fire on a crowd of people.

When the gunfire ended, two people were dead and three were injured. At the time, the teen felt he was justified and was simply “settling a score.”

The interview was a part of a series done by Oregon Public Broadcasting in 1997, titled “Kids who Kill.”

“It’s never gone,” the teen says in the video. “It’s there. It’s going to be with me until I die.”

Today, 46-year-old Willy Johnson no longer knows that version of himself.

“Most people don’t know this story,” he says. “There has to be a God because that young violent man’s heart is changed completely. I don’t think the same way. I don’t feel the same way.”

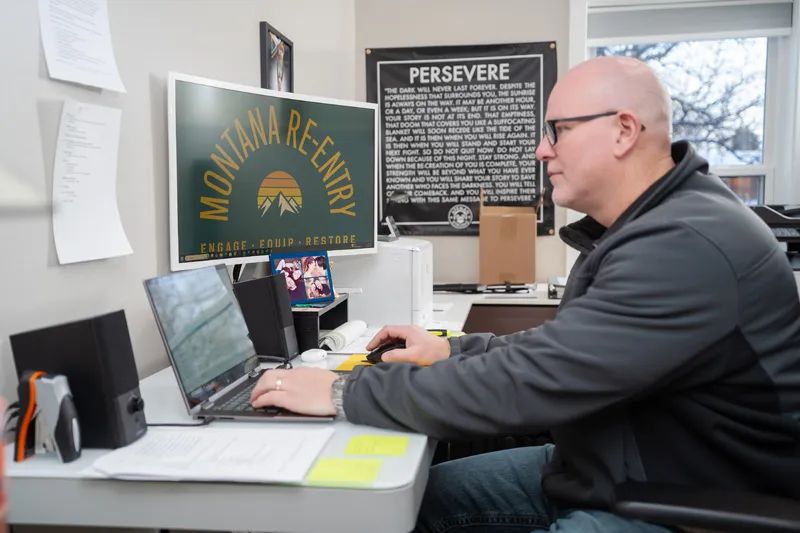

As Willy sits at a conference table inside the space he’s carved out for his new prison ministry program, Montana Re-Entry, he shares the details of his crime and what he calls the miracle that took place in the years after.

“I really thought at the time that I was going to walk out of this scenario,” Willy says. “I was so far from reality. That kid was so far from thinking that there were consequences.”

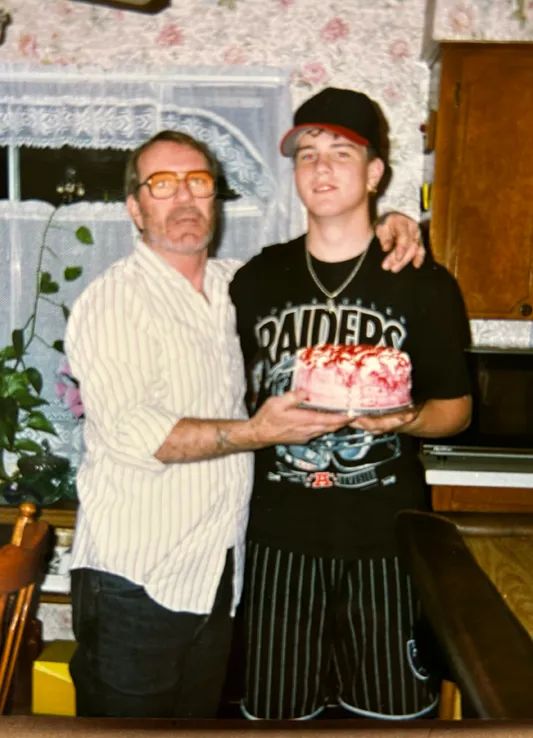

In the early ’90s, Willy spent the start of his teenage years on the streets of Salem, Oregon.

“I had a dominant mother who was abusive, with an absentee father who worked to stay away from that mess,” he says. So, Willy says, he stayed away too. He found a “family” in what can only be described as criminal enterprise. Crime wasn’t foreign to him. Both of his parents had done time in prison on theft charges.

“My dad was a Golden Gloves boxer, a bar fighter,” Willy says. “He was a go-to person for some of the ’70s mobsters. It was New York City stuff. That’s where he did his time, in Attica.” While his dad never spoke of his criminal ties, Willy says, “Even after he passed, I talked to my aunt and my cousin and I asked, ‘Is this true?’ They told me, no, it’s for real. They will vouch for him to the grave.”

As a kid, Willy watched cousins get tied up with gang life back in Los Angeles. In the 1990s, violent feuds often erupted between the Bloods and the Crips, over territory and drug profits. It was fertile ground for a 13-year-old boy looking to use violence in exchange for respect. While most wouldn’t think of Salem as Crips territory, Willy found them, and before long, he was wearing their colors.

“I was really just looking for problems,” Willy says. “If someone looked at you wrong or if someone had the wrong colors on, that’s when the problems began.”

By 14, he found himself lying in a hospital bed after a confrontation with a rival gang.

“I left that scene with 50-some stitches in my face from a baseball bat injury,” he says. “Most people would be like, yeah, I need to get out of this lifestyle.” For Willy, it fanned the flames of his anger. “I was waiting for the right somebody to come at me. I was a time bomb.”

Three months later, he says, “That’s exactly what happened. The time bomb went off.”

After a close friend of his committed suicide, Willy says, “I heard through the grapevine that there was this guy who was making fun of this whole thing,” Willy says. “The guy had no idea who this kid was associated with.”

The teen found out when Willy spotted him in a Subway parking lot one Friday night.

“I lost my head at that point,” Willy says. “I opened fire on them.”

In the end, 17-year-old Tony Sanders, a friend of the teen who initiated the trouble was dead. Erin Gordon, a 20-year-old who was in the wrong place at the wrong time, was also fatally shot.

“I didn’t even think about what had just happened,” Willy says. “I got caught the next morning.”

In the months to come, he would be tried as an adult, charged with two counts of aggravated murder, three counts of attempted murder and unlawful possession of a sawed-off shotgun. While prosecutors would paint Willy as an angry teen looking for trouble, his defense team claimed he was backed into a corner. It was self-defense. They also claimed Willy suffered from a low I.Q. and lacked the ability to form intent.

“At the end of the day, the jury almost let me go,” Willy says. “They almost said, this guy needs to go free because he didn’t have a choice. The only reason why I know that is because a juror wrote me a letter afterwards.” Reflecting on how close he came to freedom, he says, “That would have been a death sentence for me. I would have gone right back to the streets.”

Instead, Willy says, the jury found him guilty, not as an adult, but as a juvenile. He’d spend the next six years at a maximum-security youth correctional facility.

“I knew I could only serve until my 21st birthday and then they would let me out,” he says.

Three years into his time, the prison began offering intense therapy designed to help inmates come face to face with their crimes and start the hard work of rehabilitation.

“I was enrolled in three separate groups because I was so far gone,” Willy says. “One of the doctors who was running the group was the same doctor who evaluated me before my trial. Immediately, I knew he was one of the guys on this earth who could see my demons. He could see right through me.”

During what he calls a 24-hour “marathon session,” his counselors forced him to look at photos taken at the scene of his crime.

“That flipped my switch. I was forced to face who I was,” he says. “How do I fix this? You think of suicide, because in my mind, that would fix it. I wouldn’t have to deal with the pain that I created for all these families, and they wouldn’t have to deal with me coming back into society.”

In the end, he says, “I didn’t have the courage.”

He spent the next few years rewriting his life. He could no longer tell himself he was a victim backed into a corner.

“Deep in my guts, I knew the truth. I knew I was a monster,” Willy says. “That was a heavy load to carry.”

At about that time, Willy remembers “a little old, divorced lady” coming into the youth correctional facility who wanted to help some young men learn how to study the Bible. Willy and his friend, Mark, who was serving time for killing his stepsister, were the only two who took the woman up on her offer.

“She came every Sunday for two years,” he says. Slowly but surely, Willy started to peel back the layers of his troubled life.

“We were looking for something to redeem us, for lack of a better word,” Willy says. “We’ve actually taken a life. How do we move forward? I think God was already doing his thing in my heart.”

Flipping through the files he’s kept over the years, Willy recently found a reference letter from Dr. Orin Bolstad, the psychologist who led his intense therapy.

“He wrote, if you want to see that God moves and there are miracles still happening, spend some time with Willy.” With emotion in his voice, he says, “I am eternally grateful for that guy.”

Upon his release in December of 1999, Willy was sent a plane ticket to Laurel, Montana. For reasons unknown to him, it was the latest city in which his parents put down roots. Soon after arriving in Laurel himself, he was walking down Main Street to Grace Bible Church when he saw a sign promoting the church’s youth group. “I just walked in, and she was there.”

“She” was 21-year-old Julie Stene, his future bride.

“I was just hanging out and he shows up,” Julie says. “He saw the sign above the door and said, ‘I’ll go and check it out.’ He did, and that’s how we met.”

The two didn’t date for months and when they did, Julie suggested they meet up at the Railside Diner in Laurel.

“Back in the day, it was the local cop hangout,” Willy says with a laugh.

“At dinner, Willy told me his story,” Julie says. “Then, he told me the best pickup line ever. He told me he felt like God had a plan for us in our lives together. He didn’t know if it was working in ministry together or what, but he did think God had a plan for us.”

Apparently, he was right. The two married in September of 2000.

Eventually, the couple would start Alpha and Omega Disaster Restoration. In 2006, they began with just the two of them and one van. By the time they sold the company in 2021, they had grown the business to 40 employees. Selling opened the door for Willy to follow the little voice that had been pushing him toward prison ministry. He’d been working since 2018 with inmates at the Yellowstone County Detention Facility. He wanted to do the same thing at Montana State Prison, talking to incarcerated men about life and, more importantly, God.

“What they need is someone to walk next to them to get them back into society, just to be a friend,” Willy says. “I don’t have the degree. I have an experience that happened to me that shows change is possible. I’m going to go with my experience which says, you need some therapy, buddy, but you also need a redeeming God who will give you a spirit to help you make some changes.”

In 2021, he’s established Montana Re-Entry as a nonprofit organization. He’s got 12 volunteers who, on a rotating schedule, join him every Thursday in Deer Lodge to encourage a small group of inmates to take ownership of their past.

Gary Flohr, who retired a few years ago after working for decades at the Yellowstone Boys and Girls Ranch, is one of the program’s volunteers.

“You see growth in guys who are really being challenged to change their thinking and to take ownership of their behaviors, which is huge,” Gary says. Each week, up to 30 of the prison’s 1,600 inmates join them for faith-based fellowship. They read Scripture and talk about ways they can apply it to their lives. Gary says he loves walking alongside Willy on this transformative road.

“The man has a heart for people that is unbelievable,” Gary says. “He desires so much to see men change and make an honest change. We are offering that. Some of these men are going to be great citizens when they get out of here.”

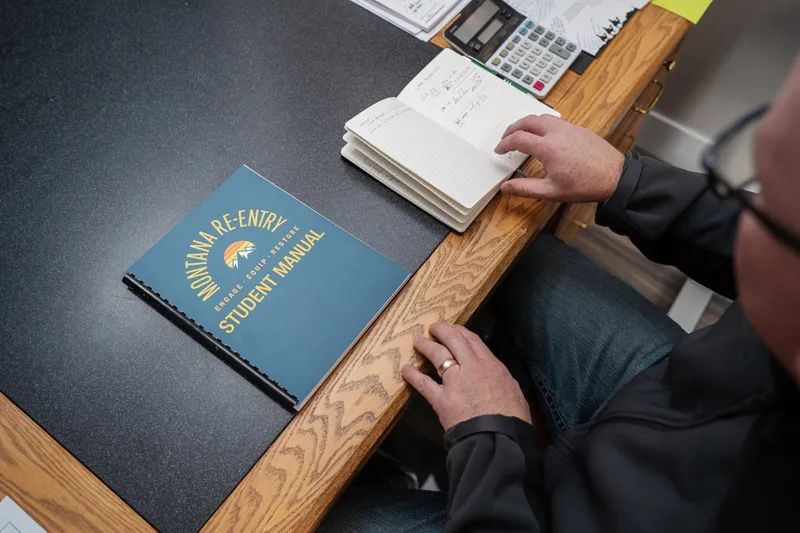

The program uses a journal and a Bible-based curriculum to help inmates get a handle on things like controlling their emotions, making the right choices, identifying stress, managing finances, and how to make sure the relationships they have on the outside are healthy ones. The program is aimed at men who are six to 18 months away from release.

“I think I’ve wanted to do this forever,” Willy says. “The minute that I realized that someone lent me some real help, I think that’s when I said, ‘Man, that’s what I want to do.’”

Ryan Morris is close to finishing out his sentence on a burglary charge. The 35-year-old has been a regular at Willy’s Montana Re-Entry weekly sessions. Each week, he says, he’s a little more equipped to deal with the everyday struggles that await him “on the outside.”

“I feel blessed,” Ryan says. “It’s a privilege to have the opportunity to talk with people who have like-minded experiences that have concrete proof that if you work these tools and use them, success is definitely an option.”

Terrie Stefalo is the activities coordinator for the Montana State Prison. She’s been with the Department of Corrections for more than two decades. She sees firsthand the impact this program is having on inmates.

“They appreciate Willy’s frankness,” she says, adding that it isn’t lost on any of them that he travels close to four hours one way to orchestrate an hour-and-a-half long program each week. “They identify with him because he was one of them. That’s a big blessing to us.”

While his nonprofit, for now, is mobile, Willy would love the day when part of the program includes pre-release housing for up to 25 men where he can help them navigate the trials of life outside prison.

“It will be a big life course with some therapy involved,” Willy says. “These guys need to know where they came from. They’ve got to figure it out. We have to peel the onion back all the way to the center.” Aside from housing, the program will offer mentorship and help with job opportunities.

Willy laughs when he says he hopes the facility looks a little like a retirement home. Each man will have his own space with his own living room, bedroom and bathroom, but there would also be common areas to help them “do life together.” Each will have his own case manager. “Then, we can sit down and talk about truth,” Willy says. “At some point, there’s going to be an instant where the switch is flipped for these guys. The light will turn on.”

Willy is thankful when he thinks of that moment in his own life. He says his biggest success, however, isn’t coming from the bottom and founding and operating a successful business. It’s his marriage.

“Julie still likes me,” Willy says. “You laugh, but I think marriage is so incredibly delicate. It’s a lot more about the other person than it is you.” The two have been married 25 years and have a 23-year-old daughter, Rylee.

“She doesn’t have any criminal class in her bones. She doesn’t know that side of the tracks. How cool is that? That’s a generational stop,” Willy says of his daughter.

While he still reflects on his past from time to time, he’s quick to say that he doesn’t overindulge in such reflections.

“People say tear the rearview mirror off. I don’t believe that. The rearview mirror is small compared to the windshield,” he says.

He knows that, through that windshield, he might just help change another man’s life.

“That one could be the next Willy, right?” He adds, “With my transformation, I give the credit to the people who stepped beside me, who believed in me. I reflect on that often and out of that is just gratitude.”

It’s his time, he says, to do the same. “I want to finish the race here. I think it will be very fulfilling.”