Hunting Down a Threat

Head DEA Agent in Montana is on a mission to turn the tide of drug trafficking

In Stacy Zinn’s office, she’s thumb-tacked a photo of 89 people to her wall, all of them known drug users who fed their addiction buying painkillers on the street. When she posted the picture eight years ago, the users ranged in age from 18 to 27. For Zinn, the resident agent in charge for the Drug Enforcement Administration in Montana, this was a way of keeping tabs on what happens to a person when addiction settles in.

“It’s been sad to see,” she says. “Some have died. Some have been arrested. Some converted over to heroin. A few pulled themselves out of it but the vast majority have not.”

When she learns that one of the people pictured overdosed, she makes a note on her board. It’s a visual reminder of the ones she’s lost in the fight.

“These were young people,” she says. “There are some that started with sports injuries. There are some who just started partying with the wrong people. In my eyes, they are just young kids.”

Zinn has been at the helm of the DEA in Montana since 2018. She’s the first female to hold the post. She started her career here in 2014 as a supervisor for the Tactical Diversion Squad, an interagency team dedicated to the trafficking of prescription drugs. At the time, she wondered what the drug culture was like in “sleepy Montana.” It didn’t take long for her to realize that it wasn’t all that sleepy.

“When I first got here, we were seeing maybe half a pound of meth on the streets at one time, maybe a pound, and that was big time,” she says. By contrast, Zinn says, in the first week of this December alone, “We seized 32 kilograms (70 pounds) of meth.”

Twenty years ago in Billings, the drug trade was fueled by local criminal families who both manufactured and dealt drugs. She says those “notorious” enterprises still exist, but today, some dangerous national and international players have started to stake their claim here.

“We do have several cases not only here but in Great Falls where we have known communications between Montana and Mexico with cartel members there,” says Zinn.

She’s seen rumblings from not only California and Detroit street gangs but both the Sinaloa and Jalisco New Generation Mexican cartels. The Sinaloa cartel, one of the strongest criminal organizations in the world, is reportedly the top supplier of fentanyl to North America. Fentanyl is a powerful synthetic opioid that is similar to morphine but is 50 to 100 times more potent. Zinn says the Sinaloa cartel has claimed the state’s reservations as their turf. It’s rival, the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, has been called “the biggest criminal drug threat” to our nation by U.S. counter-drug officials. Neither group, Zinn says, is anything you want settling into your city.

In early December, DEA agents in Denver announced that a massive raid brought federal grand jury charges against 19 members of the Sinaloa cartel. In the raid, agents seized 110,000 pills laced with fentanyl, eight pounds of heroin, 13 pounds of meth and 24 pounds of cocaine, plus nearly a half million dollars in cash. Zinn says that since Denver is a pathway to get drugs to Montana, it’s safe to say this bust affected the flow of drugs here.

While Zinn couldn’t speak about ongoing investigations, her dealings with the cartels go back two decades. Her first job with the DEA involved undercover work in El Paso, Texas, chasing down some of the cartel’s key players. In time, intelligence surfaced that one cartel had put out a hit on her life.

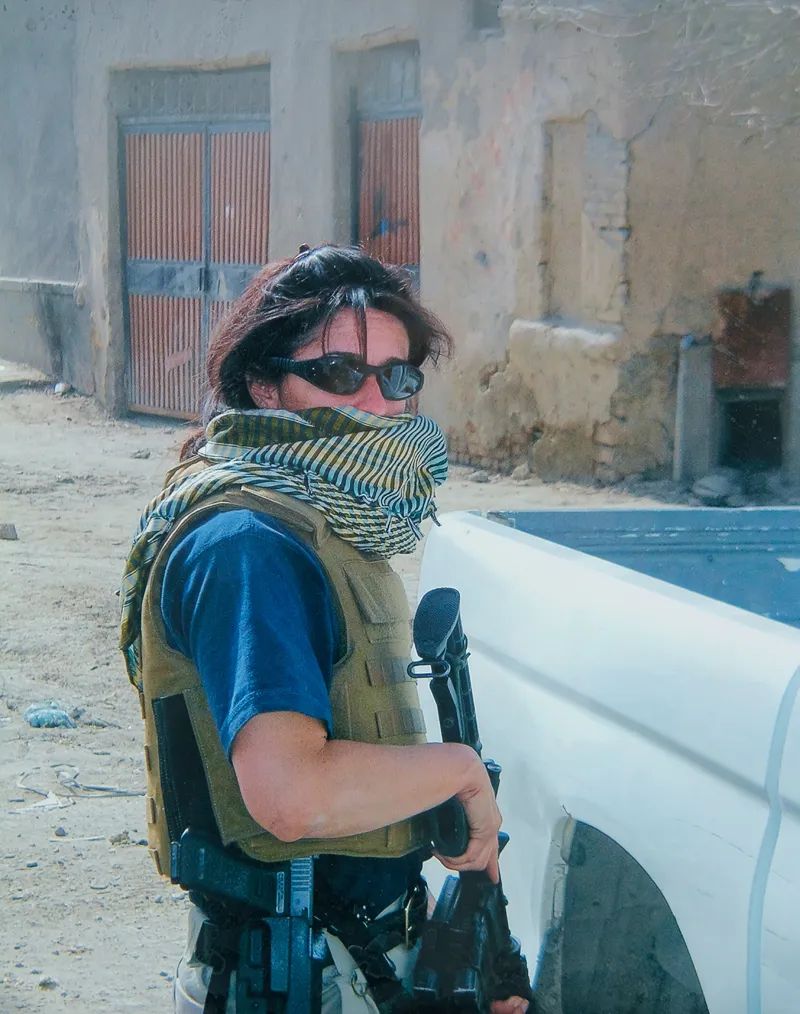

She was in the process of being relocated when, in 2005, the DEA assigned her to what’s called FAST, or Foreign-deployed Advisory and Support Team. She spent three years traveling back and forth to Afghanistan targeting the opium trade that financed both the Taliban and Al Qaeda.

Zinn’s experience in Kabul reads like a major motion picture thriller.

“We would land early in the morning, hike up about two miles up to these labs and we would determine what we had, try to gather up any evidence, seal it and then lay explosive devices, scuttle down, hike out of there and then destroy the labs,” Zinn says.

During those tours of duty, she encountered two more attempts on her life. She escaped the first when an explosive-laden vehicle ran out of gas on its way to detonate outside a dinner party full of Afghans and U.S. Intelligence operators. The second brush happened on the way to an event involving a high-ranking leader of the city of Kandahar.

“He wanted to show the world he was destroying all these drugs. We went out to a field and he was going to make a big production out of it,” Zinn says. On the way back, she says, “Our driver changed the route at the very last minute, which was a very smart move. The individuals knew who we were and they set out these little remote-control cars laden with explosive materials. They were going to detonate when we came by, but we went the opposite way.” She adds, “After that I told myself, I’ve done four tours, I am done. At the time, I was pregnant and I didn’t know it.” Her daughter is now 13.

“Everything has come full circle,” she says. “Starting off with the cartels, going international with the terrorism side. I’ve seen all levels of drug trafficking. I’ve seen the big picture. The problem is trying to convey that big picture to local law enforcement.”

As in communities across the country, drug dealing in Billings is a money grab by criminals.

“Montana is very lucrative because the cartels make so much profit,” Zinn says. She talked about the evolution of drug use. When opiates were selling for $30 to $40 per pill, she says, “Our street users started converting over to heroin. We saw that trend in 2016.” Heroin, she says, cost roughly $14 per day instead of roughly $100 for the same high on opioid pills. The only problem was, the high is elusive. “When you take that drug over and over, you don’t get that euphoric feeling,” she says. “You’re chasing the dragon. That’s what they call it.”

So the cartels found a new and dangerously addictive alternative.

“The cartels figured out that If you mix fentanyl with heroin and you take that and you don’t overdose and die, you get that original euphoric feeling — every time,” Zinn says.

It’s a high that users are willing to pay for, Zinn says, with cash and their lives. The farther away you get from the Mexican border, Zinn says, the more you pay for the pill.

A fentanyl pill in Tijuana, for instance, sells for roughly 60 cents. In Yellowstone County, that pill goes for $22. Take it farther north to Sidney, and a single pill will cost upwards of $120.

The pills look like Oxycontin, a prescription painkiller, with the same color and similar numbers and letters stamped on them. Many times when a person buys one of these pills, Zinn says, more than likely they’re actually getting “fake oxy,” or fentanyl-laced pills.

“The problem is that users don’t know how much of the percentage of that drug is fentanyl and how much is heroin. You see individuals overdosing and dying more now than ever because they don’t know what they are taking,” Zinn says. It’s estimated that two out of every five pills could spark an overdose death. “I’ve talked to many people and asked, ‘Why are you doing this?’ They tell me, ‘We know we are playing Russian roulette but it’s worth that high.’”

Last May, a bad batch of “fake oxys” led to 17 overdoses over a four-day period on the Rocky Boy reservation just south of Havre.

“My former office in El Paso, they recorded this week that there was so much fentanyl coming across the southwest border that they couldn’t stop it,” she says.

Right now, the clock is ticking for Zinn to turn the tide of drug trafficking to our area. In two years, when she turns 57, the agency is forcing her retirement. Since she was never assigned to DEA headquarters, it’s standard procedure. The agency can’t extend her time.

“I really hate to say this, but I have nothing to lose. If I say something out of bounds, I will apologize but I would rather risk that and tell the community that this is what is happening instead of being in a suit and drinking coffee in my building,” she says with passion. “If I can help one child of not going down that path with narcotics, then it's worth it to me.”

This past spring, Zinn’s team found evidence that LSD was being sold at two Billings Middle Schools.

“I pushed all of my work aside and went after this. I handled it personally,” she says. “It was just too important to me.”

She immediately teamed up with a trusted task force officer. Together they looped in school resource officers and were able to eliminate the threat from a particular cell of dealers who had been targeting students via the social media app Snapchat.

“That’s why people need to understand this,” she says. “I have 24 months left and I want to really hit the community between their eyes because I am really worried, especially with the legalization of marijuana.” She knows from experience that pot can be a gateway drug.

“I would say out of 50 people that I debrief whether it be defendants or confidential sources, 48 of them have said that their first illegal drug of choice was marijuana,” she says.

Add in the fact that many don’t understand that marijuana today is nothing like the drug smoked back in the ’70s. THC, the mind-altering portion of marijuana, made up roughly 2 percent of the drug back then. Today, it’s legal for marijuana to have anywhere from 33 to 65 percent THC. Zinn says she’s read studies that the higher THC levels can lead to psychosis-style breakdowns in a person’s developing brain.

She plans to devote a team to keep an eye on the black market that will undoubtedly move in to undercut legal sellers.

It’s just one more element of the fight.

“Coming to Montana, I saw what drugs did to families. When I was down chasing Al Qaeda, the Taliban, or El Chapo, I didn’t see what the drugs were doing. It was a cat and mouse game. Here, I see families torn apart,” Zinn says.

That’s why over the next two years she plans to put some serious mileage on her car, traveling to any town willing to listen and help her solve problems.

“We can’t arrest ourselves out of this problem,” she says. “Unfortunately, there are too many of them and not enough of us.” She noted that there are not many crimes that occur in Billings that don’t have a tie to the drug trade. “The shootings that took place at the first of the year? It’s drug based,” she says.

Zinn says if her career sounds harrowing, it’s nothing compared to her husband’s. The retired DEA agent spent time working in the jungles of Colombia hunting down criminal networks during the time of Pablo Escobar, a Colombian drug lord and narcoterrorist.

“He’s the person you call in the middle of the night if you need some help to do something that no one needs to know about,” Zinn says.

Until retirement comes, this tough-as-nails daughter of a Marine will keep her focus on the threats against our community.

“I’m fearless in my fight for this community and its kids,” she says. As she keeps tabs on every search warrant and ongoing investigation, she says, “It’s a reminder that this is a community problem. This isn’t just the DEA versus Joe Blow the trafficker. This is a community problem, and this is our community that we live in.” She adds with a slight laugh, “For better or worse, the sheriff and local P.D. are stuck with me for another two years.”

DID YOU KNOW?

- During a traffic stop in February of 2020, the Montana Highway Patrol seized 78 pounds of methamphetamine, one of the state’s largest seizures.

- Last year, the DEA in Montana seized more than 174 pounds of meth and 48 pounds of opiate pills, many of which were laced with fentanyl.

- The number of DEA-seized counterfeit pills with fentanyl has jumped nearly 430 percent since 2019.

- Criminal drug networks are manufacturing fentanyl-laced pills and marketing them to look like legitimate prescription pills. DEA lab testing revealed that 2 out of every 5 pills laced with fentanyl contain a lethal dose.

- Below, two vials show the deadly doses of both heroin and fentanyl.