Next Level Nursing

Traveling nurse takes her care to New York City

Nurse Sarah Shields will never forget seeing one of her patients leave Queens Hospital in New York to the Beatles song, “Here Comes the Sun.” That’s the tradition there when someone beats COVID-19 and is discharged. All the staff on shift takes a break to cheer on the survivors as they leave.

As the little lady walked through the crowded lobby, she took her time to thank as many doctors and nurses as possible. The woman was the first of Sarah’s patients, and one of only a few patients, who recovered from COVID-19. As the song’s refrain, “It’s all right” played over the PA system, Sarah thought of the woman’s eyes.

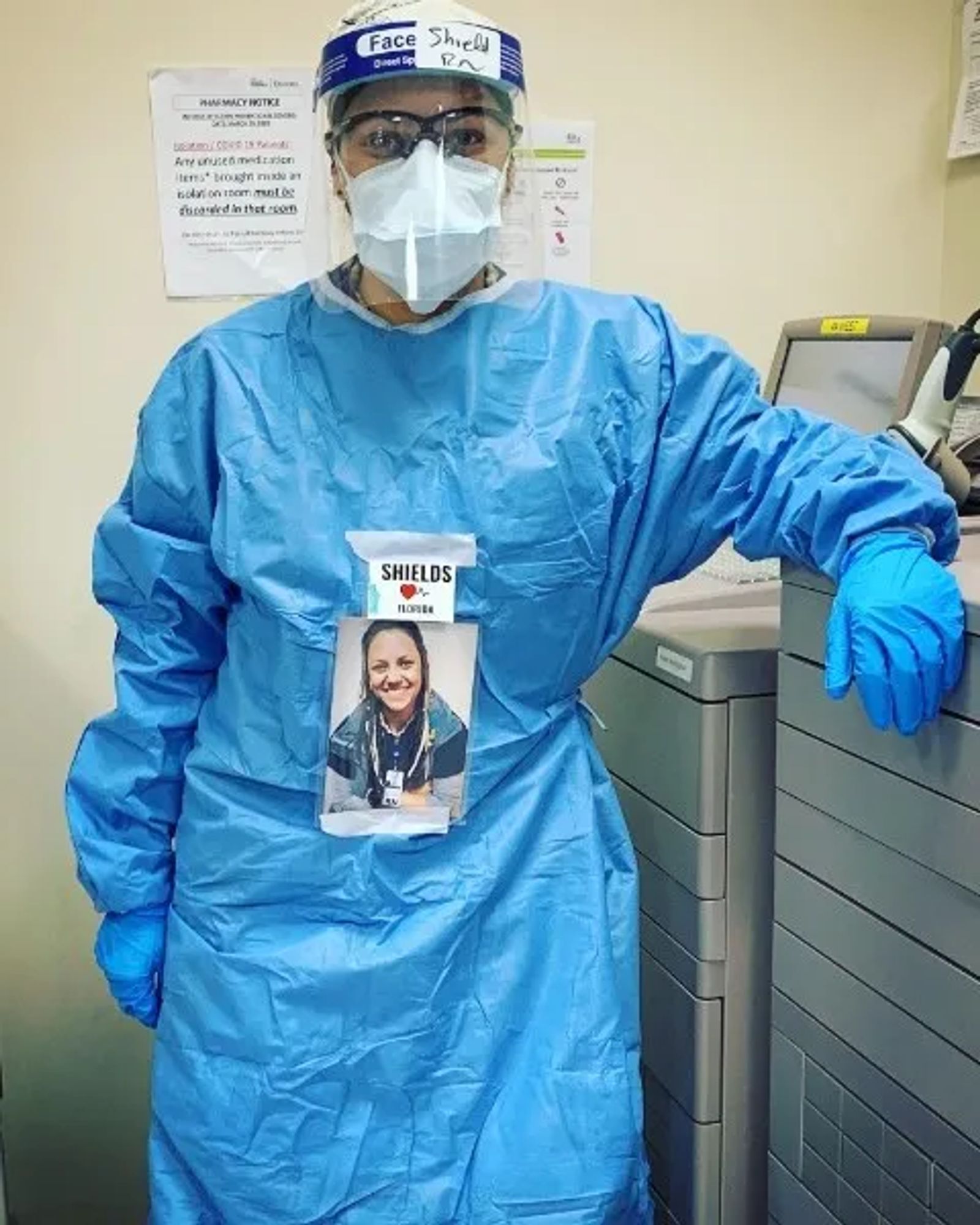

Every day for 37 days, Sarah donned a full-body surgical gown, an N-95 mask, covered by a surgical mask, goggles and face shield. On her head she wore a hair net. Only her eyes were visible to her patients. Likewise, her patients were typically wearing masks or medical equipment to help them breathe. Sarah’s speech was always muffled by her equipment, and her patients frequently couldn’t talk. Those who could spoke only broken English.

But the eyes can say what no language can, and every day Sarah’s eyes told her patients, “I’m here for you. I’ll be your advocate.”

Sarah is a travel nurse, who works at St. Vincent Healthcare. A nurse for five years now, she’s worked at various locations across the country, but has called Billings home for the last couple of years. In March, when the coronavirus hit hard in New York, she was given an opportunity to serve there. It was a risky assignment, but despite the odds, Sara decided to go.

“I knew that’s where I wanted to be,” she says.

Twenty-four hours later she was on a plane bound for New York City. Her duty assignment: Queens Hospital.

As a travel nurse, Sarah has worked in most all specialties, including oncology and palliative care. Sarah is no stranger to death and dying, but what lay ahead of her would shake her to her core.

“That first day, we opened the doors to mass chaos,” Sarah says. “It was the definition of hit the ground running.”

Queens Hospital was beyond capacity and every patient in the building was infected with COVID-19. As Sarah described it, people could be heard yelling through their masks, alarms were going off constantly. Medical staff were running everywhere. There was equipment, beds and patients stacked everywhere, many waiting in chairs for beds to open up.

“It was something you could never have prepared for,” she says. “You take the trauma scenes from movies and crank it up a couple of notches.”

She was assigned a list of patients and went to work, but Sarah soon realized her work was more of a support role for end-of-life care – sudden end-of-life care. COVID-19 was taking the lives of her patients often within a few days of being admitted. It was like nothing Sarah had ever experienced.

“I saw more death and dying in 37 days than I have in my five years as a nurse combined – and family wasn’t present for anyone,” she says.

The loss of life was relentless, but providing the best possible care was Sarah’s focus. She was motivated by her patients and their stories, especially the woman Sarah treated who was her first patient to beat the virus.

“To watch her beat COVID was a real win,” Sarah says. “It came at a time when I needed it the most. I provided her with comfort and she provided me with motivation to keep going.”

As often as she could, Sarah helped her patients connect with their loved ones, even if she could only spare five minutes. The hardest times were when she overheard the last conversations her dying patients had with their loved ones. Some were tender, peaceful moments. Some were fraught with pain. Some patients sought reconciliation and begged forgiveness as Sarah held the phone to their ear. No matter how the conversations went, they were equally heartbreaking.

“When you hear the conversations between two people for the last time, you hear a lot of things that make you rethink your everyday actions,” Sarah says. “Not a lot of things are final, but death is.”

Back home, on her rough days, she would go home and decompress, or take a few minutes during her shift to work through her feelings. The experiences at Queens Hospital pushed her to the very edge, but there was no time to think or process her emotions.

“I felt like an egg,” she says. “My shell was just getting thinner and thinner, and I knew if I cracked, I would have no time to pull it together.”

Thankfully, the strict quarantine following her time in New York gave her the time to decompress. When it was allowed, she went to the mountains where she was out of cell-phone service and unplugged from the news. There, she found restoration.

“I let myself rest physically, mentally and emotionally,” she says. “I was able to go through the emotions and thoughts that I didn’t have the time to process while I was there.”

As she reflects on her experience at Queens Hospital, Sarah has a renewed appreciation for the nursing profession, and it’s changed the way she approaches her work.

“I learned that a shared language is not necessary,” she says. “I will never underestimate what a simple hand touch will do, and the power of communicating by nonverbal actions.”