No Country Like This

The Life and Work of Poet Gwendolen Haste

Photos provided by the Western Heritage Center

Editor’s Note: Over the past century-plus, many women in the Yellowstone Valley have broken tradition, refusing to let society dictate their path in life. They’ve been comics, political activists, rough-and-tumble history makers and community champions. Under the leadership of Community Historian Lauren Hunley, the Western Heritage Center began honoring 10 of these women with its exhibit “Saints & Sinners: Women Breaking Tradition.” YVW decided to share some of these noteworthy women.

"No country that our lifetime wanderings had taken us to was like this.”

These words framed Gwendolen Haste’s introduction to the breathtaking landscapes, open spaces and homesteading hardships of eastern Montana in 1915. Her first impressions, both anticipatory and foreboding, became the foundation for poetry that would propel her onto the national stage.

Richard A. Haste, Gwendolen’s father, relocated to Billings to continue as editor of Campbell’s Scientific Farmer. Gwendolen came as his assistant editor and circulation manager. P.B. Moss, a prominent Billings businessman, had recently purchased the periodical and he wanted it published from Billings, not Nebraska. Moss saw the Scientific Farmer as a means to promote the Yellowstone Valley and Mossmain, his utopian planned community between Billings and Laurel.

Homesteaders poured into Montana between 1910 and 1920 when, according to the U.S. Bureau of Census records, our state’s population rose from 376,053 to 548,889. Folks were lured, in part, by railroad advertising that promised dark, rich soil and temperate growing conditions. For the Hastes and others, Montana was a land of opportunity.

“Gwenna,” as she was known to family and friends, was 25 years old and a 1912 graduate of the University of Chicago when she and her parents settled into a home on North 32nd Street. Father and daughter walked to their office in the Masonic Temple building downtown. Often, they ventured out to nearby homesteads where Richard talked crops with the men and Gwendolen chatted with the women about their lives.

Gwendolen may have understood homesteaders' lives, but she wouldn’t have lasted long as one. Her gregarious social nature would have wilted during long periods of isolation. She liked her vivacious friends, male admirers and busy social life in Billings, which she described as an “attractive little city.” Her preferred, self-described “clothes horse” attire of fine hats, tea dresses and elegant shoes was clearly unsuited for weeding a summer prairie garden in the hot sun or trudging through snow drifts in the long, cold winter.

A Great Falls Tribune story of Aug. 8, 1916, reported that Gwendolen was elected secretary of the newly formed Billings chapter of the Congressional Union (CU), a national organization advocating for a suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The same story notes that Hazel Hunkins was elected Billings’ CU chairman. Not too much later, Hazel, a noted Montana suffragist, was arrested and jailed for peacefully demonstrating outside the White House in support of national women’s suffrage.

In 1917, Gwendolen left Montana to work at a testing lab in a New Jersey munitions factory. Most likely, she answered the call to aid in the World War I effort. Maybe her New Jersey stint offered a needed perspective on the lives of the Yellowstone Valley women she knew who lived in tarpaper shacks and sod houses. Gwendolen was back in Billings within a year.

The romance of Montana’s last homesteading period unraveled within two years of the Haste family’s arrival. Farms and businesses failed as grasshoppers devoured crops and once fertile soil cracked from lack of moisture. Dust storms darkened the skies and Montana’s harsh climate made itself known. Amid these difficulties, Gwendolen found the themes for her best work: hardship, isolation and loneliness.

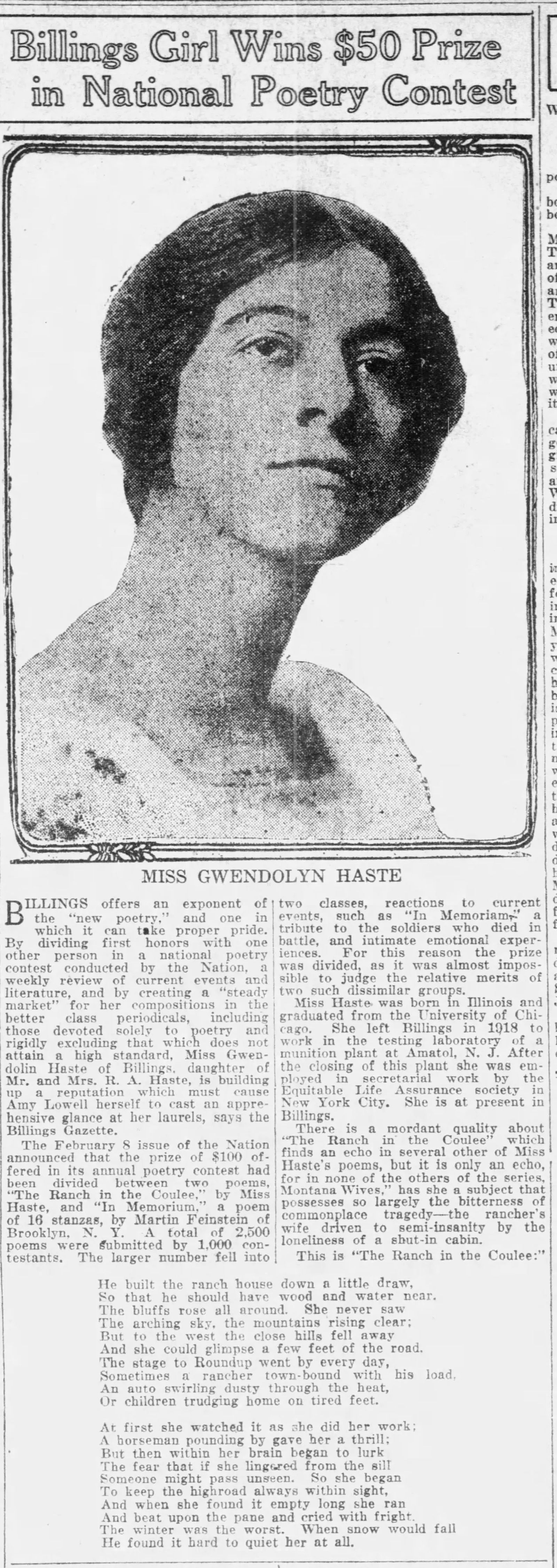

A national publication, The Nation, sponsored a poetry competition in 1921. Gwendolen submitted her poem, “The Ranch in the Coulee.” Still in print, The Nation describes itself as the “oldest continuously published weekly ... in the United States, covering progressive political and cultural news, opinion and analysis.” Gwendolen’s poem took first place and $50 in prize money.

The poem brought Gwendolen scores of letters from women across the country who recognized the protagonist’s struggle and the power of Gwendolen’s poetic voice. In a few lines, she captured the tragic existence of a despondent Montana woman, confined on an endless prairie beside a seldom travelled road, and articulated how loneliness and boredom can lead a despairing woman to madness.

Gwendolen defied expectations for women writers of her day. Her work dealt with the challenges and dissatisfaction women faced while they struggled to find purpose and meaning. In contrast, the prevailing common wisdom held that women were best suited for bearing and raising children. Art and literature were inappropriate female pursuits and frank discussion of women’s lives and work was taboo.

Richard Haste left Billings in 1923 to work for Montana’s U.S. Sen. Burton K. Wheeler in Washington, D.C. Gwendolen went to New York City armed with her publishing credentials and business writing acumen. She quickly secured a consumer affairs position with General Foods. She married in 1936, but her husband died in a pedestrian accident two years later. She retired from General Foods in 1954.

Gwendolen continued to write, and she maintained strong connections with Montana’s literary community. Her first book, “Young Land,” was published by Coward-McCann, in 1930. Her poems appeared in Scribner’s Magazine and The Frontier, edited by two Montanans, H.G. Merriam and Grace Stone Coates, and elsewhere. She joined the Westerners, a group of East Coast writers, artists, publishers and others interested in the American West. Lasting friendships with Melville Moss and Grace Stone Coates brought her back to Montana in the mid-century.

Ashahta Press published “The Selected Poems of Gwendolen Haste” in 1976. The book’s co-editor, Orvis Burmaster, lamented that Gwendolen’s later work “never came close to the power of the Montana poems.” Gwendolen died in New York City in 1979. Of her Montana legacy, Burmaster wrote:

“She spent very few years of a very long life in this state, but those few years provided her with experiences that prompted the finest verse she ever produced and helped create a poetic historical record of an important period in the development of Montana.”

Author’s note: “Gwendolen Haste: Giving Voice to the Homesteaders” by Sue Hart, Montana Magazine of Western History, Vol. 57, pp. 3 - 13 (Spring 2007) was a key source for this story.