The Many Secrets of Olive Warren

The story behind one of Billings’ first Madams

Editor’s Note: Over the past century-plus, many women in the Yellowstone Valley have broken tradition, refusing to let society dictate their path in life. They’ve been comics, political activists, rough-and-tumble history makers and community champions. Under the leadership of Community Historian Lauren Hunley, the Western Heritage Center began honoring 10 of these women with its exhibit “Saints & Sinners: Women Breaking Tradition.” YVW is bringing you a few of these noteworthy stories.

“I am going to chop (you) to pieces!” growled Calamity Jane, hatchet in hand, as she stormed the dry goods aisle of the Yegen Brothers Mercantile on Billings’ Minnesota Avenue in 1902. Some say Calamity was looking for Olive Warren, a 20-something, dark-haired, well-dressed beauty working as a shop clerk that day. A quick-thinking employee intervened, pried the hatchet from Calamity’s hands and escorted her to the front door.

If it was Olive Warren, she might have been wearing a particularly large diamond ring, a gift from a prominent Billings lawyer. According to one account, Calamity Jane and the lawyer’s wife chatted over coffee when Calamity delivered wood to the woman’s home. Calamity allegedly recognized the woman's husband as the escort of the beguiling Olive. Was Calamity’s wrath intended for Olive? Was there another motivation? The mystery surrounding the encounter sets the tone for Olive Warren’s colorful, controversial and secretive life in Billings over the next four decades.

A ROUGH START

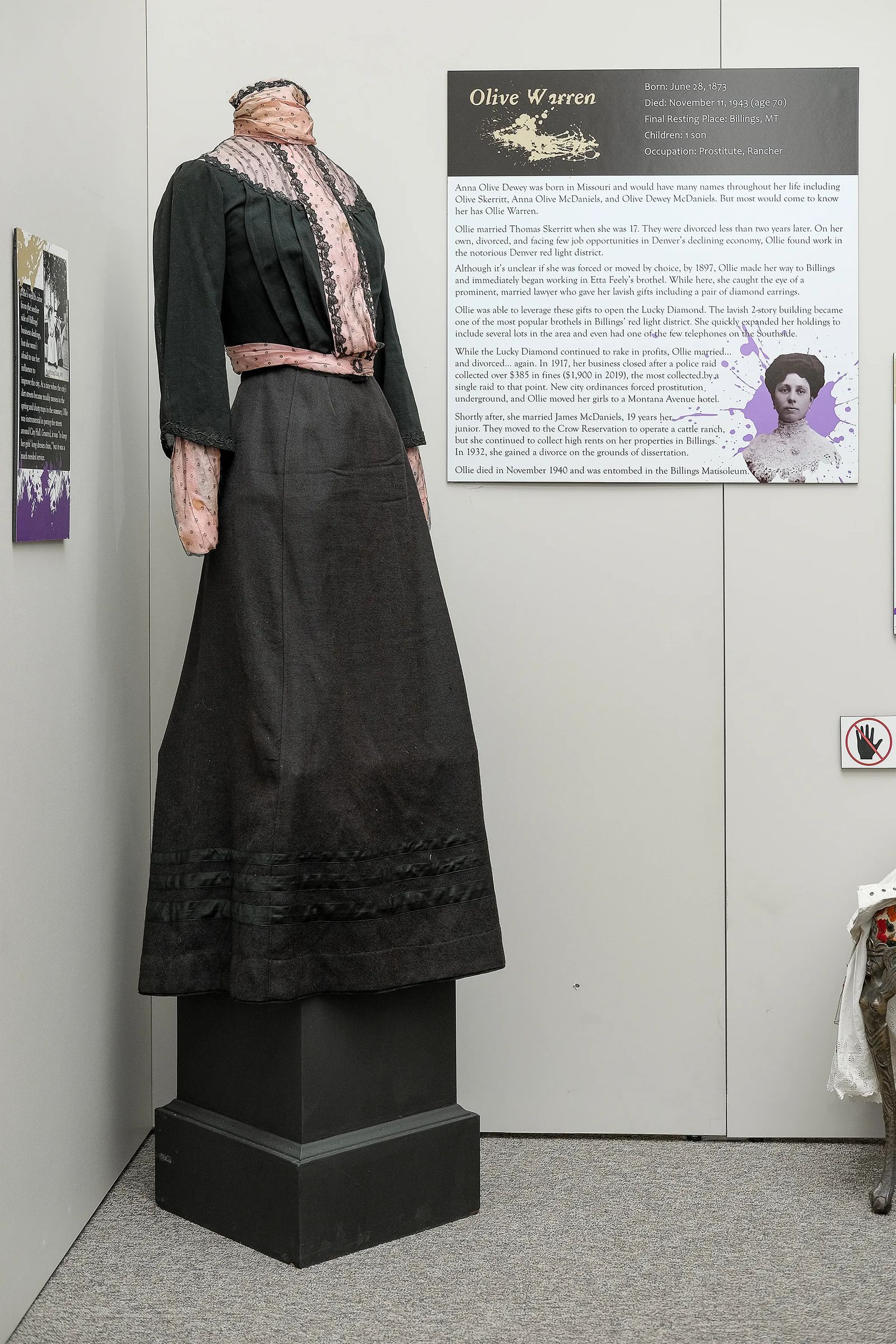

Olive Warren was born in 1873 to Missouri farmers, Jud and Jane Sands Dewey. The Deweys moved their family to Denver in the 1880s. Olive was a teenage bride when she married Thomas Skerritt in 1890. They divorced two years later.

A City Directory puts Olive at an address smack dab in the middle of Denver’s red-light district in 1897. By August 1897, she was working at Feeley’s Place, a brothel on Billings’ North Side. Its madam, Edna Feeley, had connections across Wyoming, Denver and Portland. Perhaps she encouraged Olive’s move to Billings, citing less competition and a chance to escape Denver’s depressed economy.

Young, uneducated and divorced, Olive had few options. Given her independent streak and business savvy, it's no surprise that she wasn’t content as a cook, laundress, shop clerk or seamstress.

A GROWTH INDUSTRY IN THE AMERICAN WEST

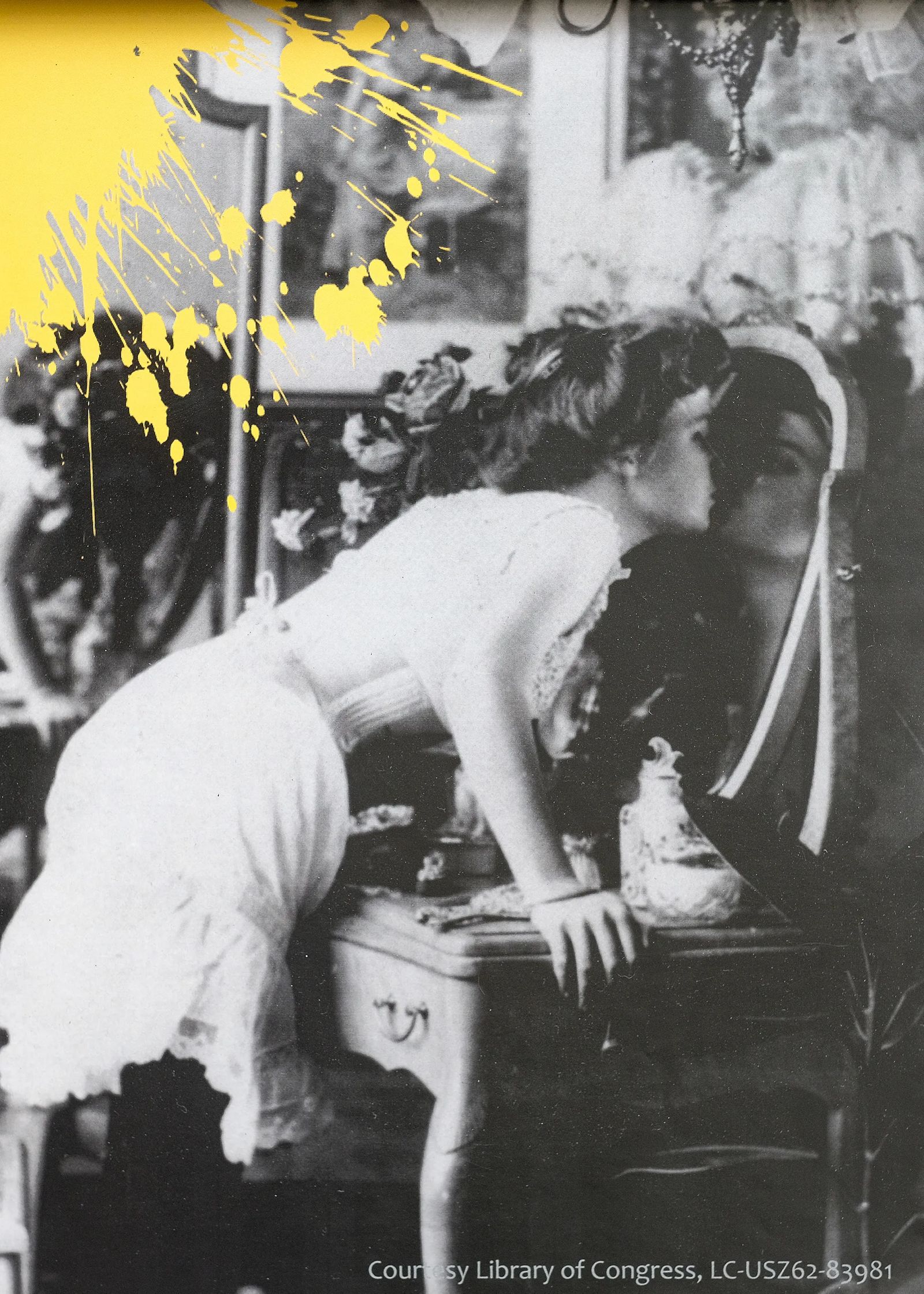

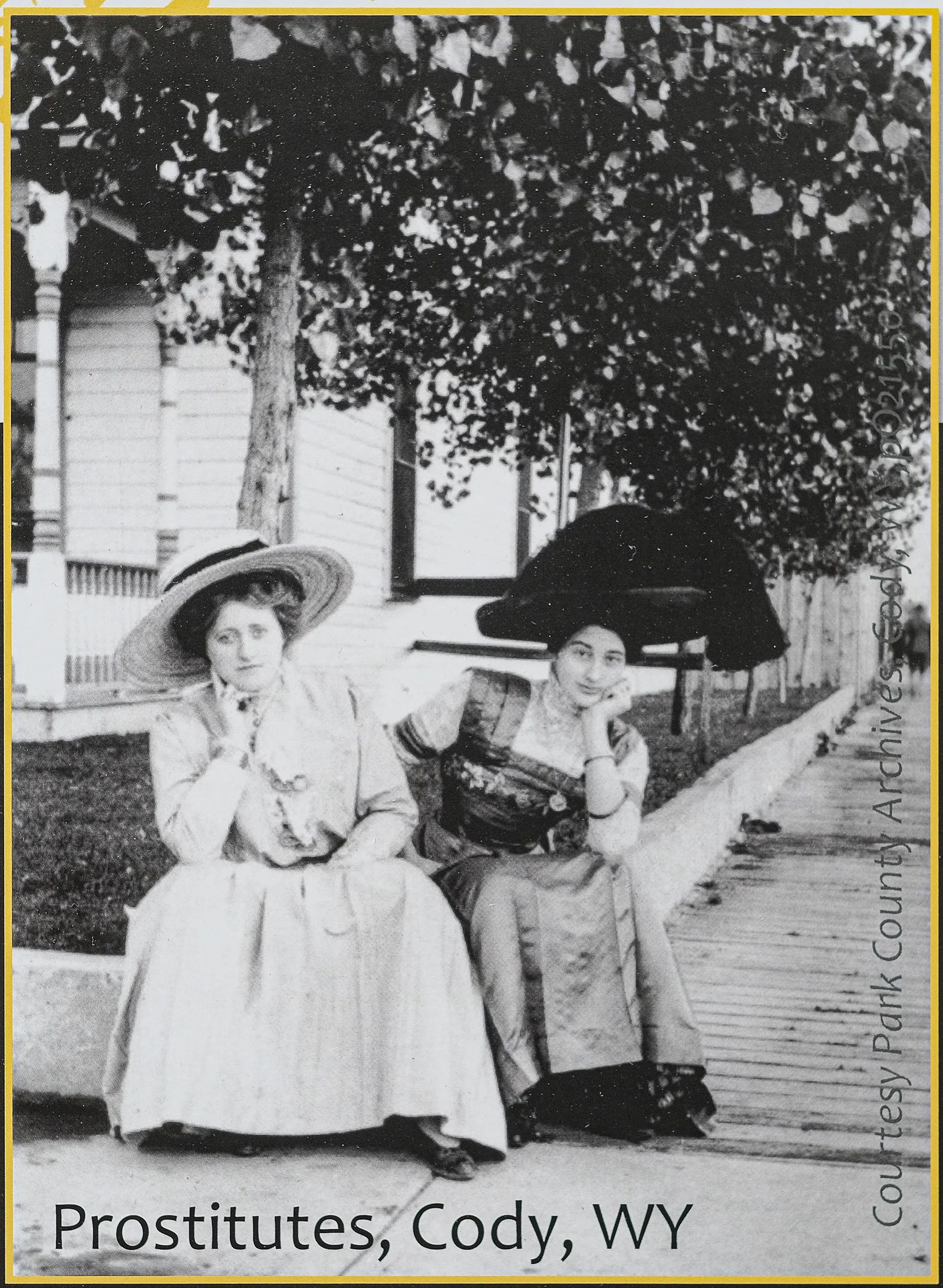

Prostitution was a booming business in the West at the onset of the 1900s. Human trafficking was a big problem. By 1910, it was illegal to lure or transport girls and women across state lines or federal boundaries for immoral purposes, prostitution and debauchery.

We’re left to wonder if Olive Warren freely chose prostitution, if she was a victim of human trafficking or if she was destitute with no other options. The world’s “oldest profession” enticed women with beautiful clothing, a nice place to live, medical care, protection from violence and economic security. For many women, those promises didn’t hold true and they turned to addiction or died by suicide. In contrast, we remember Olive as Billings’ most successful madam and one of its most flamboyant citizens.

OPEN SECRETS

Olive didn’t stay long in Etta Feeley’s employ. By 1902, city records reveal eight women lived in a Montana Avenue “boarding house” that Olive owned. “Boarding house” was a euphemism for brothel.

That same year, Olive sued Mrs. Jack Little over the wrongful cancellation of a lease, back rent and property damages at another property she owned. The judgment against Mrs. Little exceeded $7,000 in 2020 dollars. Vociferous Billings residents complained that prostitution activity was too close to Montana Avenue’s railroad depot, resulting in Olive and others being told to move off Montana Avenue or leave town.

Olive relocated across the tracks and one block south, constructing a building at 2512 Minnesota Ave. No doubt financed by the prominent Billings lawyer who lavished extravagant jewelry upon her, the new establishment became the “Lucky Diamond.” Montana’s finest brothel, it boasted a working telephone, velvet draperies, mahogany furnishings, beautiful women and a discreet back stairway.

Olive caused quite a stir when, bedecked in her plumed hat and velvet riding attire, she rode her elegant black horse side saddle through residential neighborhoods. Local society was set on its ear when, upon the death of her prominent lawyer, she sent a large horseshoe-shaped wreath covered with red roses to his family’s home. The card read, “With love, from Olive.”

Years ago, a local collector salvaged a large sandstone carriage block abandoned at 2512 Minnesota. Olive Warren’s name is carved on the top and on the street side of the heavy form. Placed just outside the Lucky Diamond’s front door, the carriage block allowed patrons to step directly onto it, thereby avoiding the muddy, dusty, unpaved street. By using only Olive’s name, one wonders if the carriage block provided camouflage for the Lucky Diamond’s front entrance.

MANY NAMES, MANY AGES, MANY HUSBANDS

Harvey Doherty married Olive in 1910.They divorced in 1917. Did Mr. Doherty figure out that Olive was 37 years old when they married, not 30 as she claimed? While they were married, it was not exactly a secret that prostitution fines and pay-offs brought in big money for city coffers. About the time of the Doherty’s divorce, the Billings Vice Commission raided Billings’ red-light district, and secured, at the time, the largest collection of fines from a single raid. The Lucky Diamond was part of the crackdown, which eventually led to its demise.

Olive said her name was Anna O. Dewey and she was 34, not 46, when she married James McDaniel, then 27. At various times, she used the names Olive Dewey McDaniel, Anna Olive McDaniel and A.O. Skerritt. During her marriages to Doherty and McDaniel, some think Olive owned a Wyoming ranch and ran a cattle operation near the Crow Reservation. Between 1929 and 1940, she managed the Virginia Hotel at 2709½ Montana Ave. In 1932, she divorced “that S.O.B. McDaniel.”

The accumulated stress of legal troubles, heartbreak, marriages and divorces, venereal disease and unwanted pregnancies among her “girls,” domestic violence, hypocrisy and sexism began to take its toll. Olive travelled to Minnesota, where she died of a kidney ailment at age 70. In December 1943, her body was returned to Billings by train. Some say her son, others say a nephew, paid for her funeral and interment in the Mountview Cemetery mausoleum, where she now rests alongside city notables like philanthropist and sheep rancher Alberta Bair and well-known architect J.G. Link.

Author’s Note: The Western Heritage Center, The Billings Gazette archives, Myrtle O. Cooper’s book “From Tent Town to City,” Nann Parrett’s book, “Montana Madams,” and James D. McLaird’s “Calamity Jane: The Woman and the Legend” were sources for this story.