The Heroes Within

The women who put community before self in the face of COVID-19

On March 13, the news came that our city had been prepping to hear for weeks. The first confirmed case of COVID-19 had sprouted in Billings. In a matter of hours, medical professionals citywide, unified by the goal of keeping the virus at bay, sprang into action. New testing modes were created. Protocols were developed. All the while, heroes rose to the surface. No one knew quite what to expect or how deeply this virus might strike, but there were people who rushed in to help nonetheless. This issue, our cover feature isn’t one woman’s story. It is the stories of a handful of women who stepped up to serve and keep our community safe in the face of stress, uncertainty and ever-evolving health information.

.jpeg?fit=outside&w=1600)

The Pathogen Police

Infectious disease specialists chart a medical plan of attack

Last December, Infection Preventionist Jordan Zepeda started to see the alerts on St. Vincent Healthcare’s medical news service about a viral pneumonia cropping up in China.

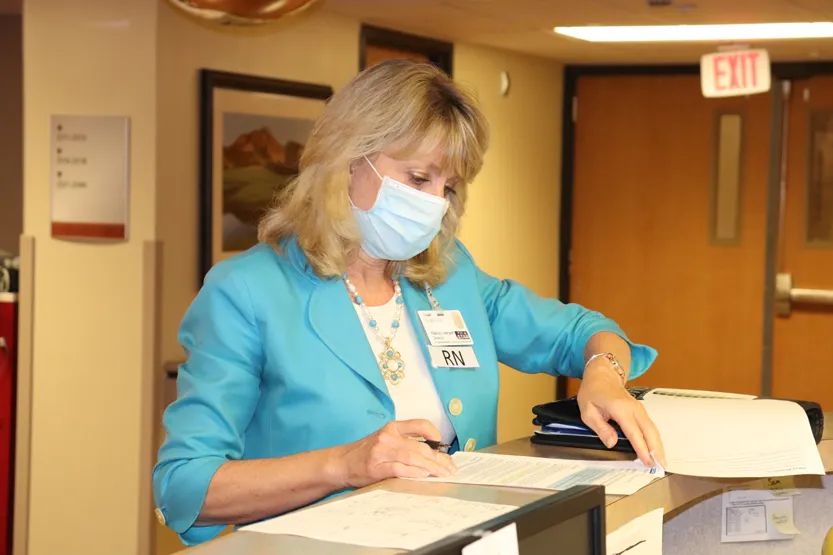

“It was on our radar, but when it hit the U.S., we had that heightened awareness,” Zepeda says. She and fellow Infection Preventionist Kathy Usuriello, R.N., did what they always do when a new virus hits: they worked overtime to study it.

“We had SARS back in 2002, so my thought was, ‘Oh, here’s another bug from China. We’ll keep an eye on it,’” Usuriello says. As time went on, and more information came to light, she says, “There was a little bit of fear because it is a new organism that is pretty virulent.”

Across the street at the Billings Clinic, those trained in containing infectious diseases also had an eagle-eye focus.

“We knew early on that this was acting like a respiratory virus in a population that didn’t have immunity, so we knew this was going to spread quickly,” says Chris Nightingale, an R.N. and a 32-year Billings Clinic infection preventionist. She and Nancy Iversen, R.N., who serves as the clinic’s director of patient safety and infection control, pored over the hospital’s “emerging pathogen preparedness plans” and stayed in constant contact with Yellowstone County’s Unified Health Command, a medical and technical team made up of people from RiverStone Health, Billings Clinic, St. Vincent Healthcare and Yellowstone County Disaster and Emergency Services.

“Why we did so well in Montana was we had time to prepare,” Nightingale says.

On a chilly evening in March, Friday the 13th to be exact, the first official COVID-19 case walked through the doors at the Billings Clinic.

“We were here at work. It was about 6 on a Friday evening and we got the call that we got a positive case,” Iversen says. “We did then what we normally do. We alerted people and tried to make sure the patient was in proper isolation.”

Nightingale and Iversen watched faces sink into fear when their colleagues discovered they had cared for COVID-19 positive person.

Over and over, Nightingale and Iversen shared the words, “You did the right thing. You wore the right things.” Iversen says, “I think we walked out of here at about 11 that night.” As she made her way home to crawl into bed, she says, three words came to mind: “Here we go.”

“The testing tent that we have out there, that went up practically overnight,” Zepeda says of St. Vincent Healthcare’s triage area designed to test large groups of people in an open-air capacity.

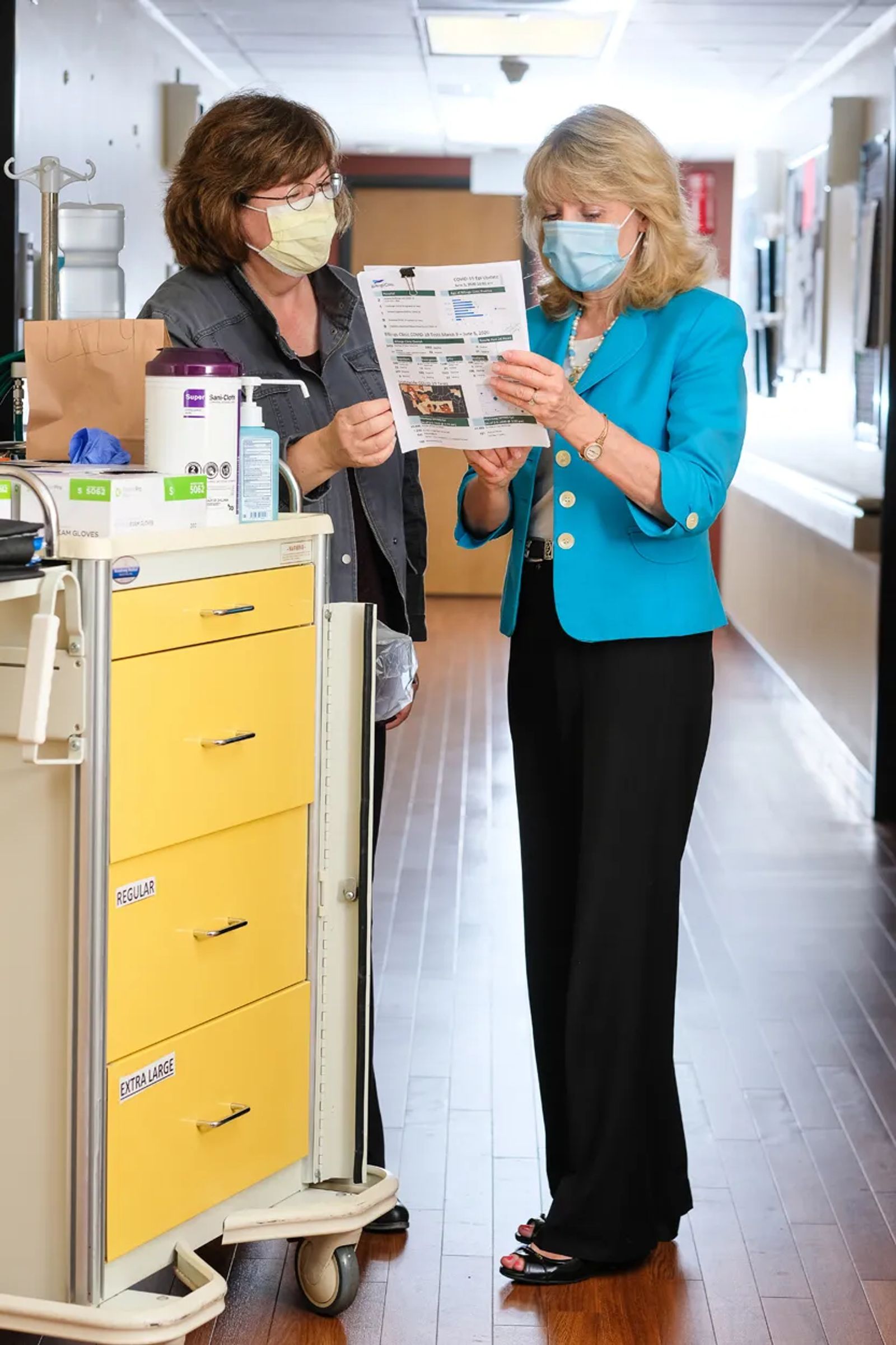

“We stood up a daycare in 12 hours because we knew schools might close,” Iversen says of the Billings Clinic’s response. “We have to have healthcare workers here to take care of these patients. We were preparing for the worst and were pleased that we didn’t see the worst like other places, truly.” She and Nightingale also met with every department head to make sure everyone was on the same page.

“We couldn’t have all the respiratory illness patients coming through every entrance at Billings Clinic, not in a pandemic that is respiratory spread,” Iversen says.

Not knowing how COVID-19 might hit our city, Iversen, Nightingale, Zepeda and Usuriello won’t soon forget the 12-hour-plus days worked seven days a week for weeks on end, just to make sure our community of roughly 7,000 health care providers had the latest information and safety protocols at the ready.

“You have this new virus show up and no matter how much we read, understand and prepare ourselves, there is new information every day,” Zepeda says. “What if we missed one little piece of information that changes an outcome?” She adds, “My phone never rang so much. We had sick patients that providers wanted to test. They had traveled somewhere. They had been in an airport. Could they have COVID? Well, maybe.”

“I will always remember the first patient,” Iversen says. “She came in after a few days of upper respiratory illness. She was very weak and short of breath. She came into same day care and within hours she had a breathing tube. She was in ICU on a breathing machine. We are grateful that we were here for her,” Iversen says. “It was just about at her two-week mark that she drove herself home. Every clinical team did it right.”

At the height of the outbreak, St. Vincent Healthcare had one person in the ICU. “We never saw a full ICU,” Zepeda says. “We did see a lot of stress and fear.”

Nightingale says Billings is mirroring what others have seen around the nation. Eighty-percent of positive cases have been mild to moderate and didn’t require hospitalization. Four to 5 percent were severe enough to need the help of a breathing machine. At the height of the outbreak, Billings Clinic witnessed eight cases in the ICU, three of which resulted in death.

“It’s terrible,” Iversen says. “You read the charts and you talk to the staff. ‘How are they doing?’ You walk up on the unit and the doors are closed. These patients have been left alone. If it hadn’t been for nursing and people going in and caring for them? We weren’t allowing visitors and that’s terrible.” Nightingale adds that this is why visiting the ICU proved to be critical, taking a little extra time to talk to healthcare workers, answer questions and calm nerves.

On a so-called normal day, infection preventionists focus their energies on what Usuriello calls the “superhighways where organisms can get in.” They keep an eye on protocols involving things like central lines, surgical instruments, catheters and items that can spread infection. They look at the roster of patients, trying to see if anyone in the hospital needs special isolation.

As Iversen says, life didn’t stop when COVID-19 hit. “We just have one more ball to juggle. It’s dynamic work with a goal of no infections.”

Last fall, Zepeda and Usuriello headed up a mock drill which they now call a “blessing in disguise.” Mock measles patients showed up and providers went through the motions of response. “At the time,” Zepeda says, “there were some measles outbreaks around the country. We wanted to be able to handle that. It was a good thing we did because it helped us find a lot of the gaps that better prepared us for COVID.”

In January, when news of the novel coronavirus was starting to heat up, Iversen traveled nearly 400 miles to Hamilton, Montana, to visit the Rocky Mountain Lab and attend a meeting with fellow infectious disease specialists. The lab is one of the nation’s 13 facilities equipped to handle the world’s most dangerous pathogens.

“It was pretty interesting. We met the lab director and one of the doctors, the Ph.D. scientist that is working on the COVID vaccine right now,” Iversen says. “They had just finished up the Ebola vaccine and they were very happy about that.” With roughly 450 lab employees, Iversen calls it one of Montana’s best-kept secrets. “Some of the publications about COVID are coming out of that lab right now.”

For Usuriello, Iversen and Nightingale, COVID-19 wasn’t their first public health emergency. All three remember the early days of the AIDS virus, caring for patients before treatment was available. They all vividly remember the measles outbreak in the 1980s. They kept an eye on recent threats like West Nile, Anthrax and the resurgence of smallpox.

“I still think I have some PTSD from measles, from HIV-AIDS, and from H1N1,” Nightingale says. “While this is scary, for me this is different. There are viral things that cause outbreaks, they just do.”

It’s why come fall, as they wait for a possible second wave of the coronavirus, all four will be looking for the signs of a spike in positive cases.

“It’s smoldering right now,” Iversen says. “We will have waves. We will have more cases.”

Meantime, Iversen hasn’t seen her 90-year-old mother since before the outbreak. She didn’t make the trek to Miles City to see her for Mother’s Day.

“I don’t know when I am going to be able to see her because I am trying to keep her protected,” she says. She wants to keep her mother safe, of course, but she can’t risk infection herself.

“We have really quarantined ourselves because we are a specialty resource and we cannot be sick.” She wears a mask at work daily and, as we talked, she thought about printing off reasons why wearing a mask is so important for a community’s health to distribute on the rare occasions she is in public.

Like her colleagues, she has been getting little sleep.

“When you have passion and purpose, it’s not work,” she says. “Yes, we get tired. There have been times it’s been exhausting. But, we always have each other’s backs.”

When it comes to the community, she says, it’s service over self. “We are not going to let someone be in a situation that is unfamiliar to them alone. Period. You just don’t do that to people.”