Where Do I Belong?

Susan Devan Harness writes a powerful memoir

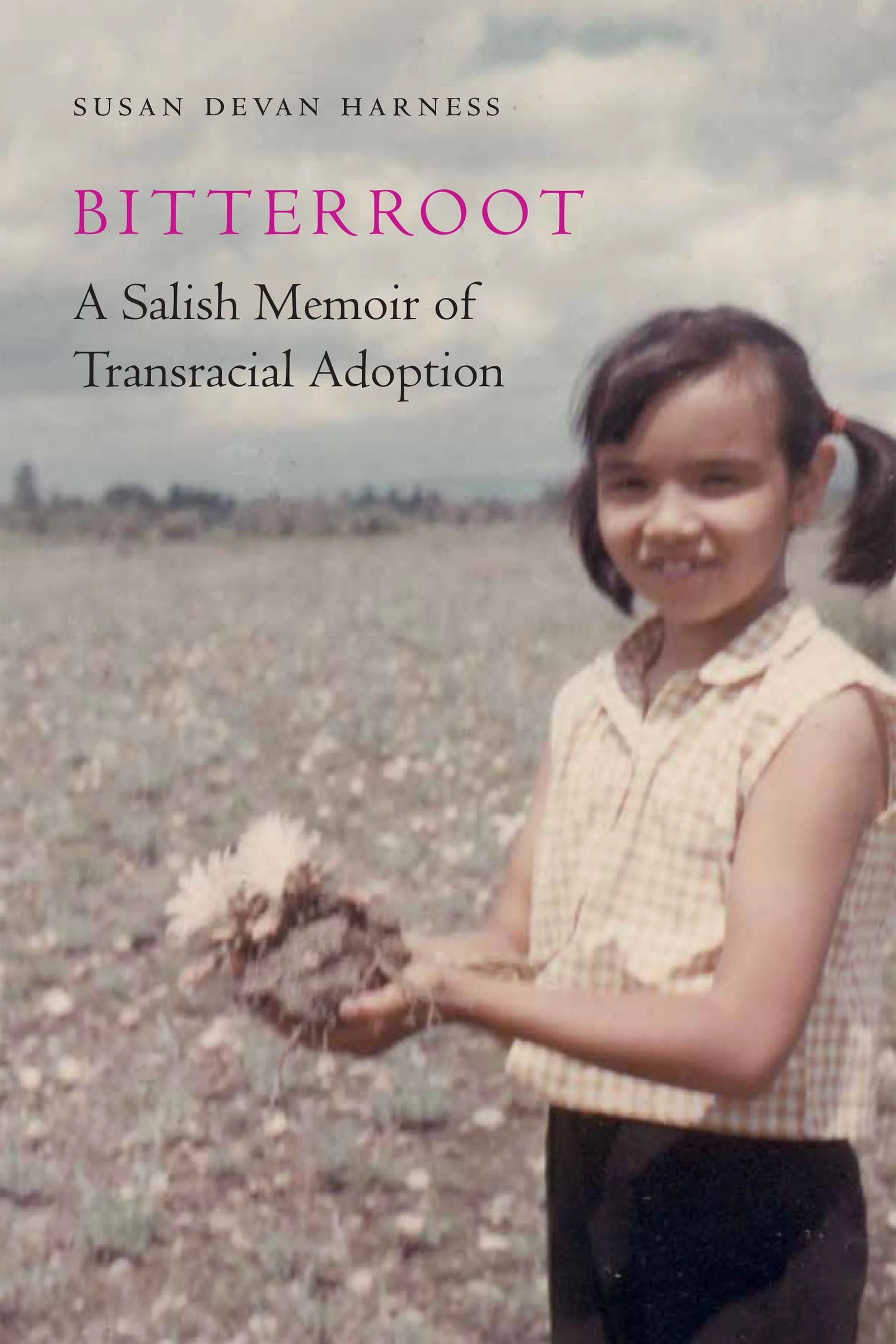

Susan Devan Harness spent decades trying to make peace with her life circumstances before she sat down to write “Bitterroot: A Salish Memoir of Trans-Racial Adoption.” Born to a Salish Indian mother, Susan was adopted by a white, childless couple when she was a toddler. The book is the personal account of her tenacious search for her birth family. It’s a story of displacement, disappointment, unexpected discovery and hope.

“I was 40 years old before I dared ask what happened to me,” Susan says. “I didn’t just write ‘Bitterroot’ for myself. I wrote it for other trans-racial adoptees so they wouldn’t feel alone in their struggle to belong in a world that tells them they don’t belong anywhere.”

The Displacement Begins

In the late 1890s, Susan’s Salish ancestors were removed from their Bitterroot Valley homelands and relocated to the Flathead Indian Reservation. Sixty years later, Susan was born. She was her birth mother’s fourth child. Five more babies followed. When Susan was 18 months old, the state of Montana terminated her birth mother’s parental rights. Her adoption followed.

With her adoptive parents' support, Susan graduated from Billings West High School and the University of Montana. During her teens and in college, Susan was uncomfortable when asked to “speak Indian” or demonstrate powwow dance steps. She’d cringe at racist jokes. She felt awkward seeing unrealistic, hyper-sexualized images of Indian women and girls in films and advertising.

After college, Susan headed for the Flathead Reservation to find work and reconnect with her birth family. One social worker told her the search “wouldn’t end well.” Another told her that “her appearance would open old wounds.” Questions to tribal elders went unanswered. Susan’s adoptive mother was understanding but heartbroken when she learned of Susan’s search. Her adoptive father was furious.

“At some level, I think my dad thought he’d failed because he didn’t change me into a white girl,” Susan says. “It was beyond a search for my relatives. I wanted to be with people who looked like me. I wanted to belong. I wanted to know what it meant to be Indian.”

Only by a Fluke

In 1993, Susan saw a letter to the editor in a tribal newspaper. A disgruntled reader opined that too many “white” Indians lived on the Flathead reservation. He was referring to Indians who’d adapted to the white world but returned to the reservation and assumed leadership roles. Susan was furious.

“Don’t blame me for living in the white world,” she wrote in her scathing reply. She signed the letter with her birth name and her adopted name. To her surprise, two of her birth sisters saw her reply and reached out with a phone call.

“We’ve been looking for you,” they said. “We told Montana Social Services we wanted to contact you. Why haven’t you responded?” Susan was stunned. For decades, she’d pleaded for information from various social workers. Her birth sisters’ query was never mentioned.

“With that phone call, my world changed,” Susan says, “and it was only by a fluke. I went from not knowing to knowing. A door opened. That summer, my husband, my two boys and I attended a family reunion.”

Pulling Back the Veil

As a cultural anthropology graduate student at Colorado State University (CSU), Susan examined how other American Indian adoptees straddled the line between the dominant white culture and their Indigenous heritage. It was the first academic research study of its kind. As she listened to other adoptees’ heart-breaking stories, she struggled with how to tell her own.

“You have pulled back the veil on a topic no one discusses,” her thesis adviser said. “Keep going.”

Susan enrolled in a CSU creative nonfiction master’s program to learn how to incorporate creative writing techniques into her nonfiction story. She didn’t want it to read like an academic research paper. As chapters of “Bitterroot” emerged, life intervened and threw Susan off track. For the next two years, she fought breast cancer and grieved the loss of her first grandchild.

“When faced with cancer and a family death, your priorities shift,” Susan says, “I moved my thesis to a shelf of lesser importance.”

Despite the setbacks, Susan mustered the energy to read selections from her thesis in 2015. The reading was well-received. Her writing advisor told her to “finish up, graduate and find a publisher.”

In late 2016, Susan sent a cover letter and two sample chapters to the acquisitions editor at the University of Nebraska Press. Two weeks later, the editor wanted to “see it all” and by April 2017, she had a contract. “Bitterroot” was fast-tracked for publication in 2018.

The Quest Continues

“Bitterroot” won the 2019 High Plains Book Awards for Best Indigenous Writer and Best Creative Nonfiction. It won History Colorado’s Barbara Sadler Award in 2021. Susan has been a featured guest at numerous writing conferences and book festivals.

The quest to uncover her story continues. She recently obtained a copy of her adoption file from the Beaverhead County Clerk of Court.

“I’m still hopeful that the state of Montana will give me access to the file that documents the time between my removal from my birth mother’s care and my adoption,” she says. There’s an air of painful resignation in her voice, coupled with firm resolve. “I deserve to know. It’s my story.”

Susan’s Reading List

A few of her favorite books

Child of the Morning by Pauline Hedge

“This is a fictional account of the life of Hatseptsup, a young female pharaoh who is barely mentioned in Egyptian history.”

On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King

“No one creates characters, situations and personalities like Stephen King.”

Centennial by James Michener

“This book showed me the importance of belonging to a place, our history with the landscape and how early history shapes our lives.”

Animal, Vegetable, Mineral by Barbara Kingsolver

“Half-memoir, half social critique, this book provided insight into how social issues affect our personal lives.”