Cover Story: Humanitarian Tricia Decker

Paying it Forward on the Arizona Borderlands

Tricia Decker vividly remembers one of her first days as a Samaritan volunteer near Tucson, where the Arizona and Mexico borders meet. This particular stretch of land includes the inhospitable and treacherous Sonoran Desert, known for its extreme temperatures, lack of water and the many days it takes to cross on foot.

It was May 2006. Temperatures were in the high 90s. Tricia was recently retired from Billings School District 2 where she spent 30 years as a special education teacher. Her college friend, Sandra, a nurse, was newly retired from the World Health Organization. It was Sandra who suggested they volunteer as Samaritans and do humanitarian work with migrants in the Tucson area.

The white four-wheel-drive vehicle the longtime friends set out in that morning was marked with a bright red Samaritan logo. Their backpacks were stuffed with water, food, first aid, hats and other supplies. Michael, a professional photographer, was the group’s leader and designated Spanish speaker. Sandra was the medical professional. Tricia would record where they were, what they saw and what they did. They parked their vehicle at a designated spot. Hiking the off-road trails, they called out in Spanish to let migrants know of their presence.

“I was so naïve in those early years,” Tricia recalls. “Migrants don’t want us to find them in the desert! They’re avoiding the Border Patrol and watching for self-appointed vigilante groups of heavily armed civilians who troll the border.”

Their hike was scheduled by the Tucson Samaritans, a faith-based organization dedicated to “saving lives in the southern Arizona desert.” Working with the nearby Green Valley Samaritans, they train volunteers like Tricia, supply hikers and vehicles with supplies and itineraries, and offer aid at sanctuary shelters. Samaritans send observers to federal court hearings that involve migrant immigration proceedings and Americans charged with federal crimes while engaging with migrants in a variety of ways.

Later that day, as Tricia, Sandra and Michael returned to their vehicle, they spotted a Border Patrol vehicle and four men huddled in the sparse shade by the roadway. The men had been apprehended on a nearby trail. The Samaritan trio stopped to share food and water and to offer medical help if needed.

Tricia will tell you that those four nameless men are seared into her memory. Feeling helpless, she watched as they silently emptied their pockets following the Border Patrol’s orders. With hands over their heads, they climbed into government vehicles and were driven away. After they left, Tricia picked up a disposable razor, a toothbrush, a pen, and a boarding pass dated May 11, 2006.

Their leftovers told how sparingly they traveled and how compelled they were to make the arduous journey. In later trips, Tricia has found, among other things, an abandoned baby sweater, a men’s shirt with money stitched into cuffs and collars, tortilla cloths and jewelry, all left by people who’ve passed by.

AN IMMIGRANT’S GRANDDAUGHTER

Tricia is in her early 70s, fit and active. She hikes in the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness, practices yoga, drives to Billings weekly to spend time with her grandson and swims at a local health club. Every summer, she visits her sisters and their families on the shores of Lake Michigan. Tricia describes her life as “very privileged.”

Back at her modest Red Lodge home after her first trip in 2006, Tricia felt humbled and challenged. She was humbled to learn of the many horrific reasons that cause people to attempt the risky border crossing. She was challenged by the response of so many Americans living near the border who step up with their time, energy and resources to meet the migrants’ basic and immediate needs.

Tricia realized that the migrants’ stories she heard in Arizona were strikingly similar to the ones her Dutch grandfather told of his immigration to America in the early 1900s. Her Grandpa Decker, the youngest of seven children, fled The Netherlands as a young man. It was during the height of the potato famine. He knew his prospects in the “old country” were dim.

Like those four desperate men in the desert, Grandpa Decker spoke no English and had only a few coins when presenting himself for entry at Ellis Island. Scared and alone, he hoped to make his way to a Dutch community in Michigan. Tricia remembers her grandfather saying, “Stars shined on me when I came to America.”

“The migrants I’ve met are deeply grounded in their faith, looking to connect with family and friends in America, resilient and willing to work hard to support their families. I am so impressed by their courage,” Tricia says. “I’m the beneficiary of my Grandpa Decker’s courage and his values. My whole life, I’ve reaped the rewards of his hardship. He was so grateful for his family and steady work in a broom factory. After my first trip, I knew I’d return. I was hooked. It was my way to pay it forward.”

DEATH IN THE DESERT

There are hundreds of borderlands deaths each year. Many of the dead are never identified. Tricia has paid her respects at the death site of a 14-year-old Guatemalan girl, Josseline Hernandez Quinteros. Josseline’s story is compelling because so much is known about her final journey and her tragic death.

In 2008, Josseline was traveling with a migrant group led by a coyote (a human smuggler). She and her little brother were going to live with their mother in California after her mother paid the man to bring them across. On the American side of the border, just outside Tucson, Josseline began vomiting and became too sick to continue. The coyote was on a tight schedule. He wouldn’t wait. Josseline insisted her brother go on with the group. Desert temperatures likely dropped below freezing that night.

Weeks later, humanitarian volunteers found a decomposing body near a creek, not far from the rugged canyon where Josseline was abandoned. The body was identified as Josseline’s because of the bright green shoes and “Hollywood” sweatpants her little brother said she wore the last time he saw her alive.

Humane Borders Inc. has documented 3,244 migrant deaths between 1999 and 2018 in southern Arizona. It keeps a grim death tally, Josseline’s among them, on a map with red dots marking where migrants have died. Some characterize the map as a “sea of red.”

Tricia is a witness to the life-and-death difference that humanitarian volunteers make. During one Samaritan patrol to drop food and water, Tricia and fellow Samaritans encountered a lone migrant from Chiapas, Mexico, which is more than 1,900 miles from Tucson.

The man from Chiapas had collapsed on the ground near a trail after wandering in the desert for several days without food and water. Lost, confused and extremely lethargic, he could barely lift his head. Tricia and others rendered immediate first aid. Although his speech was slurred, the man said he wanted to turn himself in. The group was out of cell phone range so Tricia walked to a high spot nearby to call the Border Patrol. The Samaritans tended to the man until the ambulance arrived. Tricia credits the mutual efforts of the Samaritans, the ambulance crew and the Border Patrol with saving the man’s life.

BRIEF ENCOUNTERS

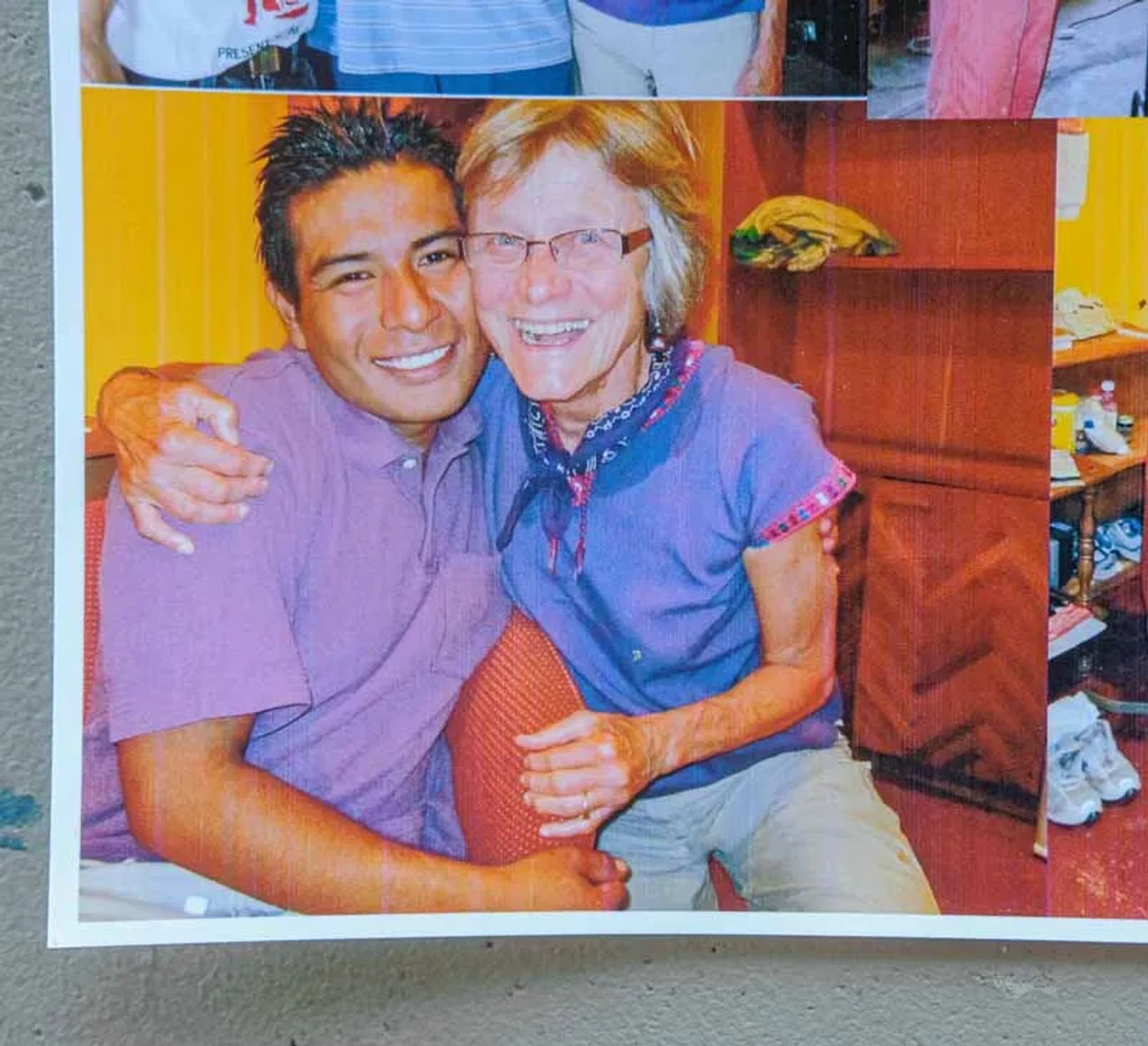

Serendipity, Tricia has learned, can bring joy into otherwise long and difficult days. During one trip, a young man named Rico, about 19 years old, came to a sanctuary shelter where she was volunteering. He was suffering from exposure to extreme heat and the aftermath of his long hike across the desert.

“Were you the ones who left water in the desert?” he asked Tricia. He spoke English. “You saved my life,” he told them. Tricia felt like she’d been struck by a bolt of electricity when she heard Rico’s words.

“Rico was the same age as my son, Mike. Mike died by suicide at age 19. I couldn’t save Mike. But our efforts saved Rico, another young man his age.”

Rico had been attending school in Florida and living with his mother. When she was diagnosed with cancer, he dropped out of school and returned to work. He was deported after a routine traffic stop. He was heading back home to Florida. With a phone card provided at the shelter, Rico called his mother, who undoubtedly felt joy hearing his voice and learning he was safe.

Shortly after Rico arrived at the sanctuary shelter, another young man turned up unexpectedly. The two knew each other. They left Mexico together but were separated when a helicopter hazed their group. Everyone scattered to escape capture and avoid the horrendous dust storm. After a celebratory reunion, they were fed and given a place to sleep. The next day, in clean clothes and shoes, and with simple, handmade bags to carry personal items like soap, a toothbrush and extra socks, they quietly moved on.

EPIC PROPORTIONS

Tricia isn’t interested in engaging in politically charged arguments about immigration. She focuses on the humanitarian needs of the people caught in the snare of legal rulings, a brutal landscape, presidential declarations, poverty and desperation. From her perspective, America has a “humanitarian crisis” on its southern border that must, somehow, be addressed.

“When I began volunteering, illegal migrants crossed the Tucson sector of the borderlands every day,” says Tricia. “They were mostly men, usually from Mexico, traveling in groups of three or four. Some were apprehended, some sought asylum and others simply passed through. Human smuggling wasn’t an issue.”

In the last decade, the dynamics on the borderlands have changed. It’s no longer Mexican men crossing the border in small groups hoping to find work in America. Large groups from across Central America, including children without parents, now seek refuge in the United States. Stricter law enforcement has forced people to traverse more isolated and dangerous routes. Human smuggling has taken root.

“The number of migrants coming to America hasn’t decreased from my perspective,” observed Tricia. “It’s just harder to get across these days, whether through a legal checkpoint or illegally. Asylum status is more difficult to obtain.”

Sandra (Tricia’s college friend) sent an email update after Tricia returned from three weeks on the borderlands in early 2019. Sandra reported that Tucson continued to reel from the inundation of migrants. A temporary shelter set up in an abandoned monastery outside of Tucson was overflowing. Other sanctuary shelters were bursting at the seams.

Recently, Tricia learned of another Red Lodge resident who’s done humanitarian work along the border. The Rev. Randall Pendergrast of the Red Lodge Calvary Episcopal Church spoke of his experience near El Paso, Texas. He interviewed women who, subject to violence in their home countries, were seeking asylum in the United States.

“These women are the absolute epitome of courage,” he told the Carbon County News. “I would have been delighted to welcome every one of them to our home and community and provide assistance to them as they build a new life in this country where they would be safe.”

For Tricia, it couldn’t be said any better.

IF YOU WANT TO HELP

Assisting the humanitarian needs at the border

HUMANE BORDERS, INC.

ON THE WEB: humaneborders.org

This group installs and replenishes a multitude of large, blue water containers at known migrant crossings near Tucson. Its mission is to “save desperate people from a horrible death of dehydration and exposure and create a just and humane environment in the borderlands.” Its website has a searchable map showing where human remains have been found. It posts warnings in Mexico to tell would-be migrants of the dangers inherent in crossing the Sonoran Desert.

GREEN VALLEY SAHUARITA SAMARITANS & TUSCON SAMARITANS

ON THE WEB: gv-samaritans.org and tucsonsamaritans.org work closely together as “people of conscience who offer humanitarian aid to migrants in the Arizona-Sonoran borderlands.” In addition to training volunteers and organizing patrols, they collect and distribute supplies and operate sanctuary shelters.

KINO BORDER INITIATIVE

ON THE WEB: kinoborderinitative.org

This initiative is a collaborative effort of several humanitarian organizations. It operates the El Comedor shelter in Nogales, Mexico, where meals, clothing, personal care items and first aid are given to those seeking to cross and those recently deported.

ALITAS CATHOLIC COMMUNITY SERVICES

ON THE WEB: ccs-soaz.org

In operation since 1933, this group operates migrant family shelters in and around Tucson, providing meals, clothing and personal care items. Of late, the Border Patrol and ICE have dropped off as many as 300 people a day at Alita sites with instructions for them to appear at later immigration hearings. Alitas volunteers help migrants contact family members in the United States.