The Changing Face of Agriculture’s Future

The evolution of 4-H and FFA

With roots firmly planted on the farm, Montana’s 4-H and FFA organizations are steadily evolving to meet the needs of the youth among the ever-changing agricultural landscape. These programs are no longer solely the realm of children steeped in the seasonality of the farm or ranch. Instead, they offer an excellent foundation for the future of any Montana student.

With a pledge emphasizing using their head, heart, hands, and health to the betterment of their community and their world, 4-H began as a way to teach the older generation research based methods. Set up through the land-grant university system, enacted during the 1862 Morrill Act where the federal government gave states public land to be used to establish colleges that offer an agricultural emphasis, as well as topics anyone could study, clubs were established to transfer practical information.

Todd Kesner, Montana 4-H State Director, says while universities were learning new techniques and systems that worked well in agriculture, convincing producers was less successful. “Are they going to take a chance on new research, or do what their father or grandfather did?” poses Kesner.

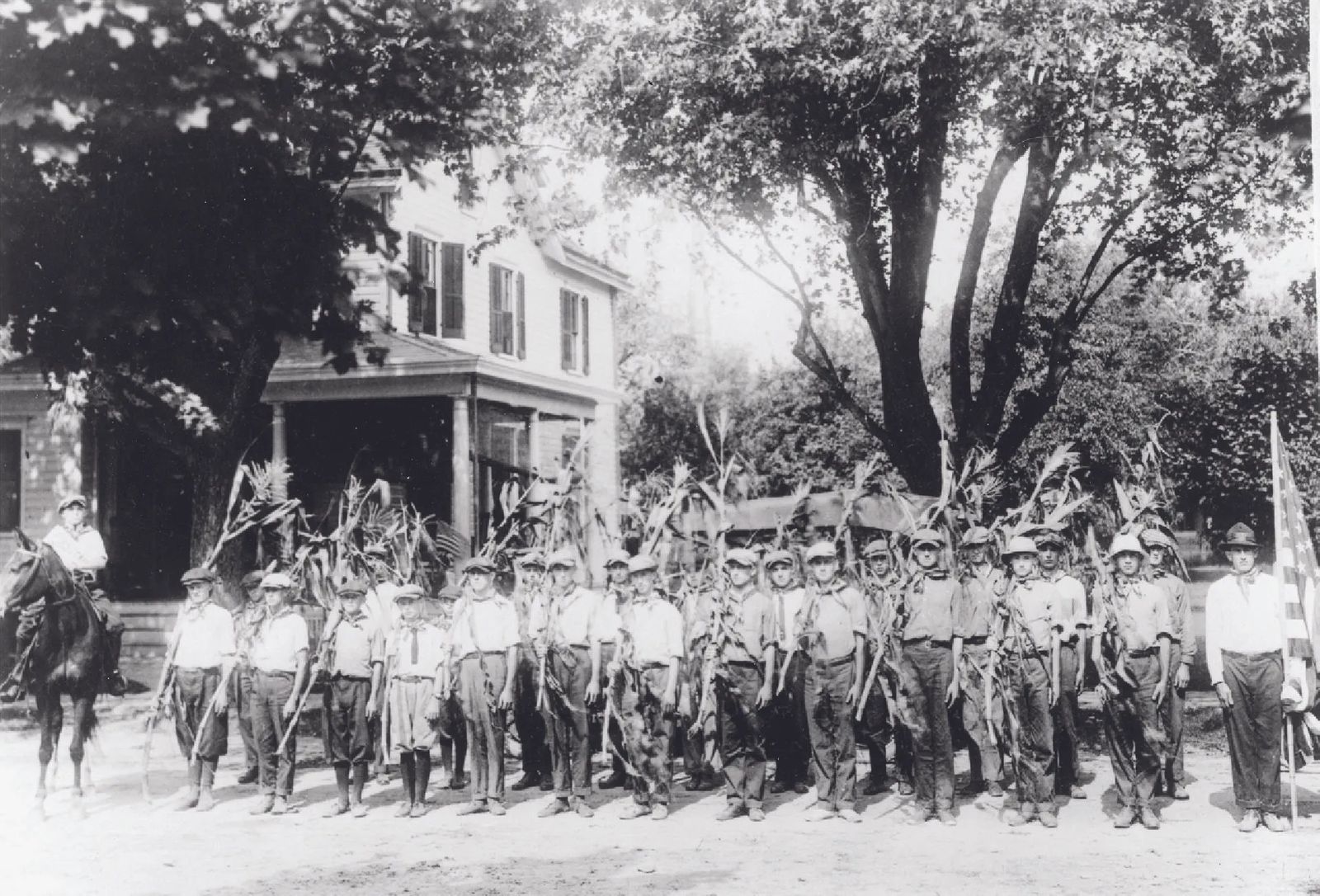

The answer was educating the next generation. In 1902, what’s considered to be the birth of the 4-H concept, began in Clark County, Ohio.

Kesner says, “Corn Clubs for Boys was a way for young people in agriculture to experiment with corn crops.”

“They were seeing huge results,” he says. Through techniques encouraged by the research, instead of harvesting 40 bushels per acre of corn, these young men were bringing in 219 bushels. Results like these were hard to ignore.

“It was a way to educate the parents through the kids,” says Kesner.

While the boys raised corn, the girls had Tomato Clubs. “The tomato clubs were pretty much a canning safety project,” Kesner says. Once again, while homemakers were accustomed to putting up food using old methods, the new pressure canners used safer techniques to preserve food, but it was difficult to persuade mothers and grandmothers to change.

From these clubs, Kesner says, “The Corn Clubs and Tomato Clubs blossomed into more and more 4-H programs as we went forward.”

By 1914, the Extension system came into being, and in 1924 Montana developed its first 4-H program. Since its inception, 4-H evolved to meet the needs of the kids of the day.

There’s no question 4-H has deep roots in agriculture, yet over the decades it’s evolved into something broader. From robotics to public speaking, every project provides a skill useful beyond the specific topic. Kesner points out when a student takes livestock to the fair and is interviewed by the judge, they are learning the same skill set needed for job interviews or in the workplace.

“The idea behind it is you’re learning life skills,” explains Kesner.

Dr. Aimee Hachigian-Gould’s two sons, Brandon and Andrew, spent a decade in 4-H doing everything from livestock projects and leather working. Although her boys are graduated from college with degrees in hand, Hachigian-Gould is still a leader in 4-H in Cascade County.

“Although Andrew and Brandon did many projects related to agriculture, they also focused on other areas. The common threads were communication of ideas through the spoken and written word, independent and group learning and working collaboratively for the good of the group and individuals. Those are skills that are needed in any discipline in life,” she says.

Besides competitions, 4-H offers life competence in other areas that sometimes fall by the wayside in our busy schedules. Hachigian-Gould says, “They learned how to cook so I didn’t worry about them when they went to college.” They were also a force to be reckoned with at the Montana State Fair in both the open and 4-H divisions for years.

4-H also played a big role in financing their college education. Hachigian-Gould says within a year’s time they drove to 17 states and 4 Canadian provinces to attend regional, national, and international competitions earning scholarships that helped pay for their degrees at Montana State University. They received job offers within their career fields during their college career and beyond thanks to their 4-H experience.

“These are all opportunities open to these kids if they want to jump in and do it,” she says.

Polson student Victor Perez is taking full advantage of his 4-H group. He joined 4 years ago because a friend was in it, and is now the president of his club.

And while Perez has done well with livestock, earning reserve grand champion with his hog in 2016, his keen interest in wildlife biology inspired him to take on entomology, forestry, and wildlife projects, among several others.

Perez appreciates students can choose a program within their comfort zone, or they can reach into an area that piques their interest. From robotics to leather working or photography, there’s a 4-H program for it.

“There’s something for everyone,” he says. “There are even things like fashion design where you design your own clothes and take them to the fair.”

Perez says an integral aspect of 4-H is also community service. He says their group takes ownership of cleaning up areas in town, as well as helping community members who can use a hand with projects. This is the norm for clubs throughout the state who understand the importance of being an active part of the community.

“What we’re trying to do in the long run is to produce someone who will be a constructive citizen,” says Kesner.

Throughout the century, 4-H has grown well beyond corn and tomatoes. With a little guidance, the kids who participate emerge with a broader education and deeper understanding of how to be a productive member of their community.

A kindred organization, Future Farmers of America was inspired by a need to not only educate the young people in progressive farming techniques but to inspire them to remain on the farms, as many lost interest during the tumultuous 1920s. In 1928, the first FFA members held their convention with 33 students from 18 states in attendance in Missouri. In 1930, Montana became the 38th charter.

FFA is different from 4-H in the fact that it is an intra-curricular program with classes taught within the school, versus the extracurricular activities of 4-H, yet with the same emphasis on hands-on education and productive endeavors.

Sheridan Johnson, Conrad, Montana FFA State President, was raised in a wheat growing family, so FFA is in her blood.

“When I was three my brother was the state officer so I was always going to these events,” she says. Yet, it wasn’t until their chapter came to her middle school to explain the program to the students that she thought it sounded like a good idea to take the ag classes. She laughs that she didn’t realize her mother planned on her to take them whether she intended to or not.

Johnson explains that FFA is one of the three components in an agricultural program model that includes a classroom/laboratory facet where the kids receive ag or science-based instruction, a Supervised Agricultural Experience (SAE), along with the leadership program of FFA. Everything the students do in the iconic blue jacket of the organization ties into their ultimate goal of an extensive and well-rounded experience.

Leadership is an enormous focus. Johnson notes the entire month of June encompasses leadership training and courses, and she found her niche working with the FFA alumni.

Although Johnson grew up farming, she has interests beyond wheat. “I had a poultry production SAE,” she says. “I’ve also experimented working in our chapter greenhouse.” She’s planning on job shadowing for an agricultural communication program to explore the possibilities for her career.

She says FFA is always adapting to the needs of the students, even if they never grew up on a farm like many of the students in more urban areas, such as Missoula. This is where their studies change to fit what they require.

“It’s really all up to you. You can go wherever you want with it,” she says.

Johnson is heading to Montana State University in Bozeman in the fall to pursue a degree in agricultural education communications with the intent to continue into biotechnology so she can communicate what she will learn with rest of the world.

For generations, 4-H and FFA taught students to expand their horizons through engaging projects. No longer purely the realm of the agricultural-minded, both organizations have evolved with the times to stay relevant in both rural and urban areas. The result is teaching young people the value of hard work, leadership, and community service that will undoubtedly touch lives for generations to come.

TO JOIN A 4-H GROUP, contact your local Extension office. There are numerous clubs throughout the state, or if your region doesn’t have one in your area, the agents are more than happy to help you start one that’s tailor made to the area’s needs. In some situations, you can also participate “At Large,” although the club organizations allow more opportunities for leadership roles on a regular basis.

Since certified agricultural or science focused classes are an integral aspect of an agricultural education, students who wish to join FFA must enroll in agricultural classes within their school. If this is not available, Montana students do have the option to take classes through the Nelson Academy of Agricultural Sciences Online (www.allagonline.com) to fulfill this aspect of the program.