Voices in the River

An Essay by Sarie Mackay

When I was a child, I heard voices in the river. The Little Bighorn brimmed with legends—that was widely known—but I heard real voices, with a cadence and pitch that made me strain to figure out who was down by the water. My grandmother, her arms elbow-deep in the suds of the cabin sink, would tip her head toward the river and say, “It’s the current, shuffling the stones, and the sound of the wind in the water maples.”

Her own voice had always been a little tremulous, like the purling eddies along the river’s bouldered bank. But there was nothing timid about her. The youngest of ten children born on a Fromberg homestead, she was a teacher, gardener, cook, botanist, author, and guide.

When I sat on the porch floor of the old cabin back then—it is nearly one hundred years old now, but to me it was old in the 1970s—listening to Elsie and her friend Genevieve, I formed my earliest notions of women as heroes.

They are both long gone, but I think of them as the sun slips over the east wall of the canyon on summer mornings and highlights the pine branches with silver. That shimmering light is a phenomenon, something my family and I swear is unique to the Canyon. Elsie and Genevieve were phenomena themselves—just ask anyone who knew them. Was there something about life in the remoteness of Montana that created women of exceptionally strong stuff? My contemporaries and I pause often in midlife to chart course-corrections, but these two women always seemed to know exactly where they were going.

Elsie, a stalwart community leader of Laurel, Montana, was the mother of a son and two daughters. Genevieve, who had two children herself, was the daughter of Baptist missionaries who sought to bring Christianity to the Crow Tribe, or as they are truly known, the Apsaalooke—Children of the Big-Beaked Bird. That is the two of them in the trimmest possible terms. But together, as I knew them in the Bighorn Mountains and in the small communities of southeastern Montana, they blended into one composite— a strong, elegant frontier woman of the mid-twentieth century.

Genevieve’s parents, Dr. William and Anna Petzholdt, endeared themselves to the Crow Tribe not so much for bringing them the Bible but rather for creating a local school that saved their children from being sent to US government off-reservation boarding schools. From my earliest memory, passing through the Crow Indian Reservation was a thrilling part of our two-hour journey from Laurel to the Little Bighorn Canyon, and from these trips I gained a sense of Crow Indian culture. My grandmother often insisted that we stop at the Baptist Mission in Lodge Grass, a wood-paneled sanctuary full of stillness and spirit, to say hello to Genevieve.

Genevieve’s mother, Anna, was adopted into the tribe by Mrs. Ben Spotted Bear. Her father, William, was so beloved by the Crow people that White Man Runs Him—one of the few scouts who rode with General Custer—loaned him his own name, a great honor. Genevieve herself was adopted and was called, “Looks to the Mountains.”

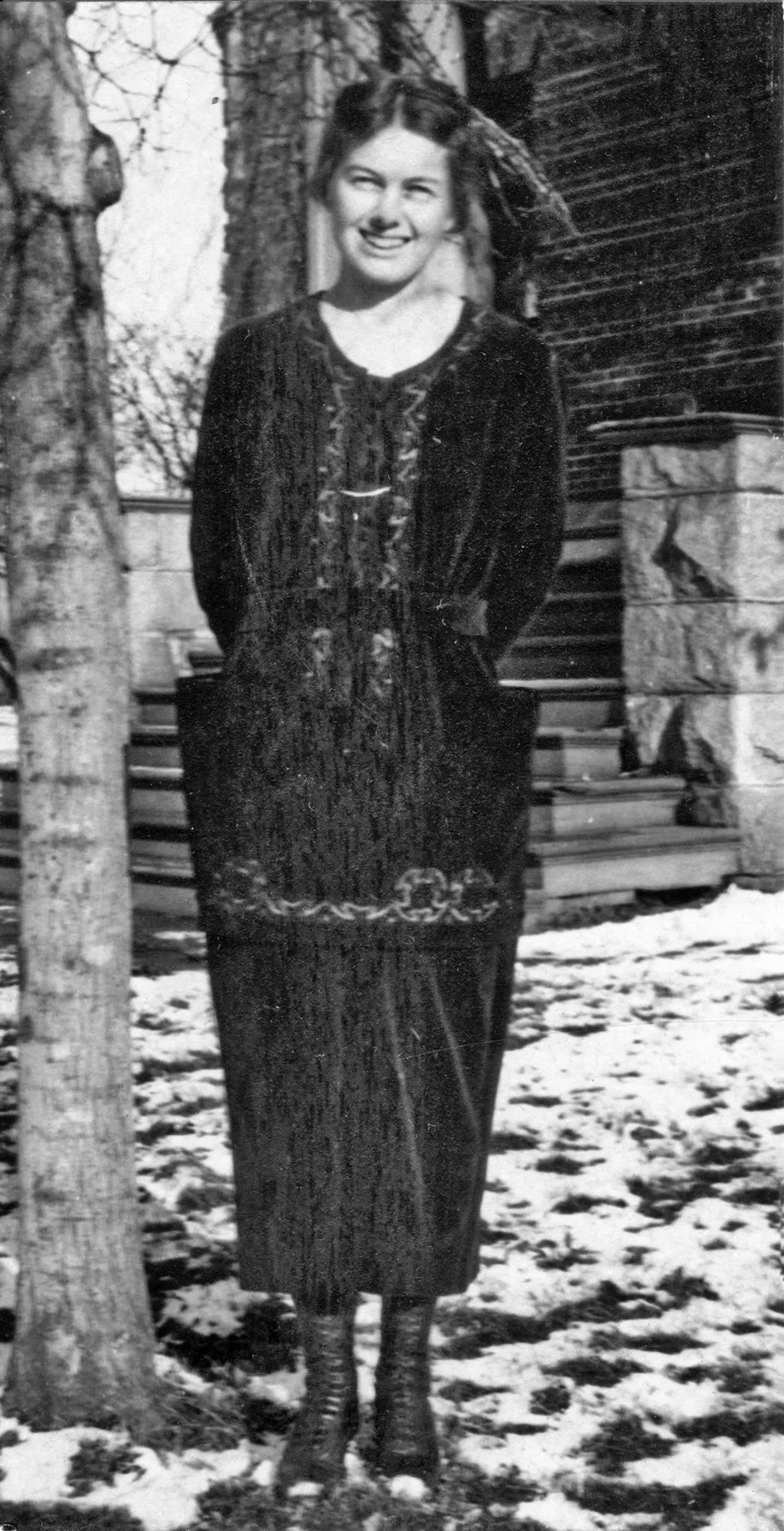

The two women met in the 1920s. Elsie Pokarney had left what she calls her Czechoslovakian-Bohemian parents and their Fromberg homestead, moving to Wyola, Montana, to take a teaching job in a one-room schoolhouse. She soon caught the eye of the local lumber man, Paul Johnston.

Paul courted Elsie for several months. During this period of time, Charles Lindbergh, who frequently buzzed in and out of remote areas of the Midwest, made an emergency landing in a field south of Wyola. At a dance that evening, my grandmother did the one-step with the dashing young pilot. “I can still see him in his tailored breeches,” she reminisced to us. Then, with a girlish grin, she added, “Of course he danced with me. He knew who could kick a wicked foot.”

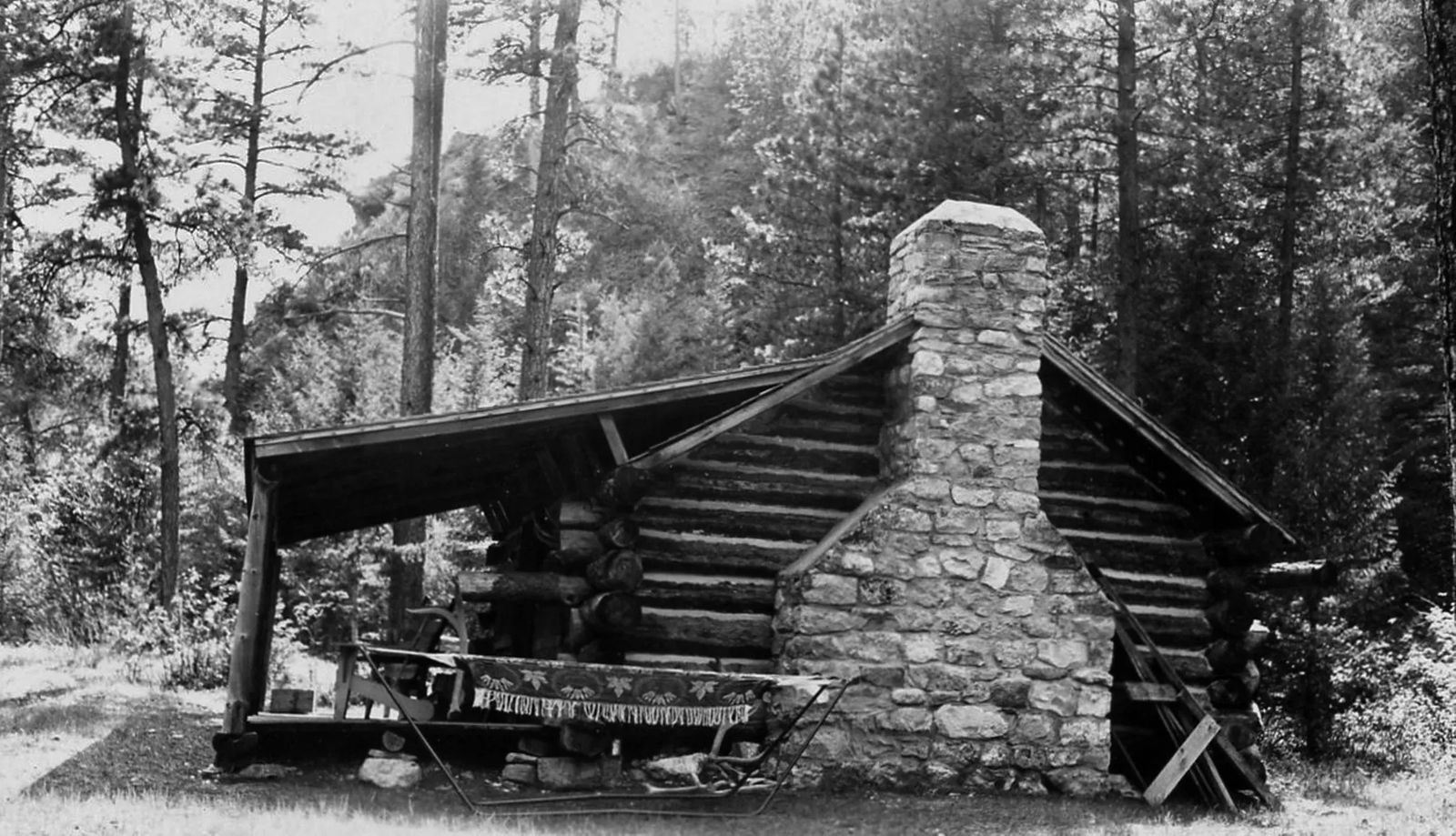

Nobody’s fool, my grandfather proposed to Elsie a few days later, and they were married in late October of 1924. In due course, Elsie met Paul’s friend Jay Fitzgerald, an accomplished ranch hand and carpenter, and soon made her first bumpy, wild ride via Model T to Paul’s hunting cabin in the Bighorns. This one-room log cabin was the genuine article, built by Paul in 1918 with the help of a bona-fide French mountain man, John Tailleur.

Jay and Genevieve Fitzgerald built a cabin too, a stone’s throw from Paul’s. But Jay Fitzgerald built his alone and, like a painting, it bore his artistic stamp. In the embrace of these two summer residences, my brothers and I did a lot of growing up, as my mother, her siblings, and the Fitzgerald kids had done.

The Canyon was a hallowed place back then, and still is. A chasm cut by the Little Bighorn River out of one of the country’s oldest geologic formations, it hums with the mystery of the Medicine Wheel and legendary elk herds. Its steep limestone and granite sides are lined with Douglas fir, Ponderosa pine, and mountain mahogany. Along the river, poplars and dogwoods lean over the water, trailing faded nets of last year’s wild clematis, and ouzels pipe their wild song. It was here, influenced by these two women and their love for the Canyon, that I first felt the stirrings of what would become lifelong convictions about humanity’s connection to the land. I began to see that it does not belong to us; rather, we belong to it.

Tales were told on the Johnston’s cabin porch about snake bites, close calls with mountain lions, and about the time John Tailleur’s wife, up on Elk Horn Creek, confronted a bear with a cast-iron frying pan and got the best of him. That porch was wide enough to accommodate numerous guests who got down from their horses or who lay their fishing rods aside to sit in sturdy rocking chairs, eat peach pie, and spin yarns.

When the sun sank behind the canyon wall and the dinner dishes were washed, the children slept on cots on the porch, never mind the stories about the lions and bears. All we cared about were the fireflies and the hooting owls, along with the hot flat rocks from the wood cook-stove that warmed the cold sheets. Fifty years later, we still put those iron cots on the porch.

Like my grandmother, Genevieve Fitzgerald was a teacher. Genevieve created a professional life for herself that Elsie—required by her busy husband to cease working outside the home—never knew. Wyoming-born, tall and slender, Genevieve had a patrician bearing one tends to associate with old New England families. She held herself with a dignified, Katherine Hepburn kind of grace, with loosely upswept hair and chiseled cheekbones to match. Oddly, Elsie resembled Genevieve, in the uncanny way that good friends sometimes remind us of each other.

Although Genevieve was pretty, the most captivating thing about her was her facility with the English language. She too spoke like moving water, but her voice was easy and clear, like a river that suddenly sharpens up in June and reveals everything. Words I had never heard before tumbled as easily out of her as the Little Bighorn poured over its cobbled bed a hundred yards away. Sitting on the porch floor, I heard the two of them banter about community, gardening, or bird-watching, and at times venture into the mildly profane region of canyon gossip: so-and-so has a paramour, or such-and-such couldn’t build a campfire to save his neck.

Genevieve gets a good share of the credit for my lifetime love affair with words. Her parents, William and Anna, were scholarly people who transmitted classical values to their bright and inquisitive daughter. Great travelers, they brought treasures and domestic refinements to embellish their life on the reservation. Their ranch house near Lodge Grass—recalls my mother, Patricia Johnston—was like a museum.

While Genevieve sparked my passion for the English language, Elsie lit the fire of natural curiosity in me. Although she stopped teaching professionally, she made her children and grandchildren her students, and when that didn’t satisfy her, she expanded to the community of Laurel and took on the Girl Scouts and even the local juvenile delinquents. The community’s grande dame of gardening, she was up before dawn and loved to weed in a light rain. It’s an urban legend in Laurel that “Elsie planted every tree in this town.” In her spare time, clacking on a little Royal typewriter, she wrote and later published the ponderous history book, “Laurel’s Story.”

Sharing the wonders of nature became the path of least resistance in reaching the hearts of the young and sometimes intractable. It certainly worked with me. Even in her dotage, she never lost her capacity for awe and wonder. She went back to college and graduated at age sixty-five.

When I rode along with my grandparents to the cabin on weekends—on the old road, before the wide gray ribbon of I-90—we often stopped in Lodge Grass for last-minute groceries such as eggs or cream, or a dozen ears of corn. I recall the old Apsaalooke women scuffing along the worn floorboards of Stevenson’s Grocery, in their bright shawls and hard leather leggings. There was something magical about that world of dust and warmth and color. Now I know I felt the same amazement that Elsie brought to the banquet of life.

As the years passed, Elsie and Genevieve renewed their acquaintance every summer without fail. I have often reflected on how Genevieve must have helped my grandmother through the sudden loss of her young son, and what tenderness Elsie may have given to Genevieve in her own times of trouble. Children and grandchildren grew up and moved on, but their canyon conversations continued, whether anyone was there to listen or not. My grandfather Paul passed away in 1976, and Genevieve’s husband Jay died a year later. Widowed but not alone, they kept up their friendship and correspondence.

Genevieve was older than Elsie, and her health began to fail in the late 1970s. I had just started my own family, and at a time so focused on new beginnings, I did not like to think about Genevieve going away, but she did. The first week of April, 1982, we learned that she had passed.

It was a clear but chilly day when my mother, grandmother, and I drove to Lodge Grass for the funeral. As the whites and the Crow gathered around the grave, so did the casket-bearers, gray-haired men in worn boots and western jackets. I saw Genevieve’s family, and couldn’t help looking again at the Crow women, whom I had furtively studied with such awe in the old grocery, years ago. They were in their best attire—dark brocade shawls, wide leather belts, and dress leggings of white deerskin.

After speaking a brief prayer, the Baptist minister made a gesture toward the Crow elders. A lanky white-haired man, nudged off his folding stool, spat upon the ground and stood up. This was John White Man, son of White Man Runs Him, the famous Crow scout. John lifted his face to the snow-dusted Bighorns in the distance and opened his mouth in Crow song. All his companions picked up the chant, and the spring wind carried it across the valley.

My grandmother, standing behind me, saw my heaving shoulders and leaned forward to whisper, “Look at the sky.” I took her advice, since I was undone with emotion and it seemed like the only thing to do. While the Crow chanted their tribute, my mother, grandmother, and I watched the luminous white clouds and bore Genevieve heavenward with our gaze.

We had Elsie with us for another fifteen years, until 1997. My mother and I still make many trips to the Canyon every summer. We still find an occasional columbine in the fairyland of Genevieve’s cabin garden, and we still stoke the gleaming woodstove that was Elsie’s pride and joy. And now, on those silver mornings or lazy front-porch afternoons, when I hear the river talk, I catch a faint murmur of laughter, and I know who it is.