Mary Walks Over Ice is Paving the Way

Empowering & Educating those in Native American Business

Growing up, Mary Walks Over Ice worked on the family ranch in the shadow of Chief Mountain on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation. With her parents, three brothers and two sisters, she remembers moving cattle, feeding the pigs, and tagging along on projects with her dad, who worked as a civil engineer.

She feels connected to Browning even though her ancestors hail from the Assiniboine, Gros Ventre and Turtle Mountain tribes. Her dad and mom (who worked as a home health nurse) taught her a strong work ethic, one with an eagle-eye focus on empowering native people.

“We were there at the foot of the Rocky Mountains and it was just the most beautiful place to grow up,” she says, glancing up at a canvas print of Chief Mountain that hangs in her office at the Native American Development Corp. (NADC). She adds, “It was a really great life.”

Today, Mary leads the NADC’s Procurement Technical Assistance Center. She sits down with Native American business owners and shows them — step by step — how to secure government contracts. With each client, she’s working to build a stronger economic base for the reservations in the four-state area that her office serves.

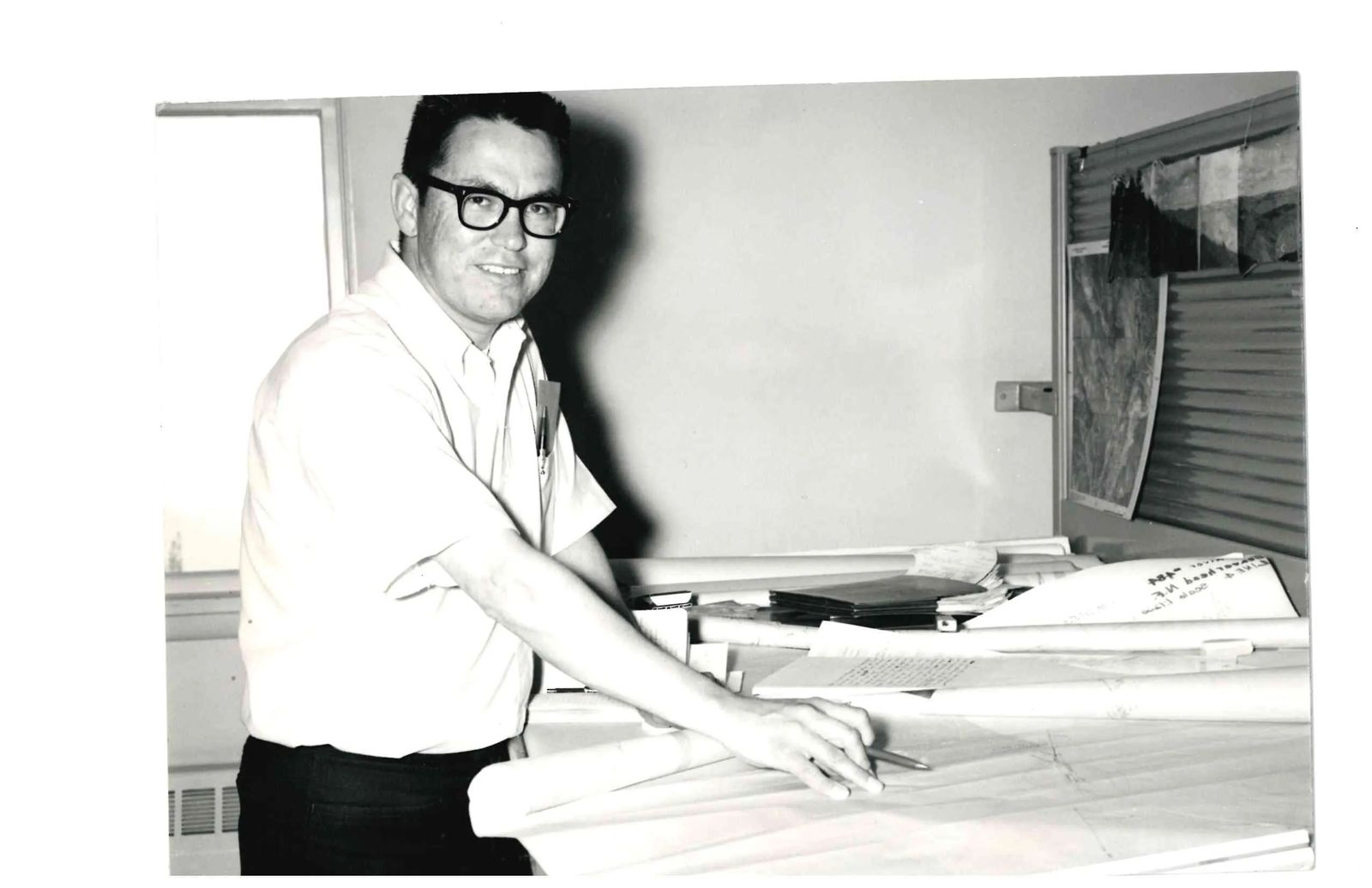

“I grew up in the small-business world,” Mary says. Her dad, Chuck Archambault, was her most important role model. After working in civil engineering for the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, he grew tired of the bureaucracy, Mary says.

“He felt like he could help more if he had his own business,” Mary says. “He quit his job with six children. My mom was a little unhappy with him, but he took his retirement out, got an SBA loan and started his own business in September of 1973.” Forty-six years later, Archambault and Company is still in business.

By the age of 10, Mary was by his side helping in his office and, unbeknownst to her at the time, was soaking up what it takes to handle project management.

“Here I had been learning that my whole life,” she says. “I started doing some of the admin parts in the office, writing letters and helping my dad with specifications and just being there for the contractors that we hired on the job.”

Woven through everything her father did was loyalty to his roots.

“There’s something my dad once told me. ‘Every day, from the moment I wake up till the moment I go to bed, I am going to work for Indian people, whether they like it or not.’” When Mary would ride along on different projects on one of the 17 reservations her father served, Mary says he told her, “There’s not one reservation in a six-state area that doesn’t have something that I’ve built. I did it out of respect for and with the help of those communities.”

Over the course of many years, Mary would come to wrestle with a future career in medicine. Mary thought at one point she’d become a doctor. She eventually graduated from Montana State University with a degree in microbiology with an emphasis in environmental health. She’d land a job at the Environmental Protection Agency in Denver as a regional tribal liaison. But the family called her back to Browning when a fire destroyed the family home and business.

After working at her father’s side for about a year helping to rebuild the company, she moved to Billings where the NADC hired her for a special project. Then-Executive Director Linda Pease persuaded Mary to serve as their Air Force liaison. It was a part of an initiative set up by U.S. Sen. Max Baucus to encourage the federal government to do more business with Native American communities. Working with her dad, Mary says, “I knew tribal and state procurement policies.” She was ready to learn federal policies to lend a hand to Native-owned businesses.

By the time Mary had been in the job for a few years, she was married and had a family. Her father, meantime, was down to a one-man operation. A tough market forced him to downsize. When a huge project came along to build 90 houses on the Pine Ridge Reservation, he took it and asked for Mary’s help.

“It was one of the best things I’ve ever done in my life,” she says. “I realized then that I had the same desire as my mom and dad — to work in Native American communities. The Natives were the first true entrepreneurs and we needed to nurture that spirit.”

The project became a crash course in tribal relations, workforce recruitment, grant writing and all the red tape that comes with it. This time, her brother, Sam, who had since gotten his civil engineering degree, joined them on the job.

“I learned so much in dealing with the bureaucracy but also trying to make sure that the people knew we were there for them. We were the resource. We were the liaison,” Mary says. “Pine Ridge is a tough reservation and I was a little nervous. I won’t lie.” They battled budget shortfalls, politics, and a workforce that didn’t always want to show up.

“We did the best we could to get the project finished and handed off to the families. We got about halfway there when the politics finally won and the project stopped. The biggest lesson learned for me was the importance of relationship building and establishing trust and how, if you do those two things right, it will help you throughout your life,” Mary says.

Even today when Mary sets foot on the Pine Ridge Reservation, “I still know the contractors. They still know and love my dad.”

In 2009, Mary would make her way back through the doors of the NADC, this time as head of the Procurement Technical Assistance Center. The mission with the center is simple. Mary says, “It’s really set up to help our Indian businesses to get into the federal, state, local and tribal marketplace.”

In the decade Mary has been at the helm, she’s helped Native American businesses sign more than $300 million in contracts, $42 million in the last year alone. Plus, she’s put on more than 400 workshops and networking events.

Martina Real Bird is one of Mary’s clients. As a 39-year-old enrolled member of the Crow Tribe, Martina once owned her own retail store. She also worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ road department, so she knew how to negotiate a contract. She felt it was the perfect mix of experience to start her own contracting firm.

“We started in September and are just getting things going to make it all work,” Martina says. While she had plenty of doubters before she opened Otter Wallace Ltd., Mary was never one of them. “She is so brilliant, honestly,” Martina says. “She never tells you that you can’t do something. She always directs you and puts you on the right path.” It’s a path that Martina hopes will have her negotiating deals for federal contracting, oil and gas exploration, construction and distribution.

While Mary has witnessed much success, she knows every day is just one more step in an uphill battle to change decades-old problems on reservations in Montana, Wyoming, North and South Dakota.

“We’ve studied how much money comes into the reservation, how much goes and how much stays in the community. It’s basically a sieve and it’s pretty much like that on every reservation,” Mary says. “We are helping the tribes understand their role in strengthening the business environment, strengthening that private sector and understanding what it means to keep that dollar in the community to help it grow.”

To further those aims, Mary helped launch the NADC’s Entrepreneurial Center, which provides assistance with marketing, management, strategic planning and one-on-one counseling to Native American business owners. She sits on the Montana Indian Business Alliance as well as the National Association of PTACs. When she heads to Washington, D.C. for her board meetings, she doesn’t miss a chance to check in on Montana Sens. Steve Daines and John Tester as well as Rep. Greg Gianforte. “Even if you have nothing to say, go, shake their hands, say hello and tell them what you are doing,” Mary says.

Turns out, she’s always got plenty to share.

Mary is a part of the team working with Billings Works to create a Native American workforce development program. And in 2018, she helped negotiate a deal with the Indian Health Service to allow the NADC to manage the Billings Urban Health and Wellness Center, a medical clinic located at 1230 N. 30th St. that serves urban Native Americans.

“We’ve heard there is upwards of 14,000 Natives living in Billings,” Mary says. “That’s the potential.” In addition to medical care, the center secured grants to provide behavioral health, suicide prevention programs and chemical dependency services as well. Mary knows these programs are a big part of empowering Indian people.

“They are saying that intergenerational trauma is a part of our DNA. I am not sure I am quite there yet with that theory, but I do think that living in an oppressed environment definitely affects how you are going to live your life.” Mary adds, “What we try to do here is say, ‘Yes, that all happened and it is affecting you in a negative way, but you kept your culture and your resiliency. Let’s build on that.’”

Just down the hall from Mary’s office sits a strong ally in the fight. Leonard Smith is the executive director of NADC and has been championing the same causes for decades.

“We believe in giving those natives who want to do something better in their lives a hand up, not a handout,” Leonard says as he talks about how alike he and Mary are. “She understands my vision and why we are doing this. We’ve grown so fast over the last few years and it’s been a real struggle for us to keep up with it. I just don’t think I would have been able to do it without Mary’s help.”

It’s why when Leonard retires in a few years, he plans to hand the keys over to Mary.

“I have some really big shoes to fill,” Mary says. “Leonard reminds me of my dad so much. He’s taught me so much. Between those two, they keep me humble and keep me true to the mission of the organization, which is to make our communities a little bit better.”

As Mary speaks in her office, in the course of an hour, loved ones of two generations walk through the door to pay her a visit — her 20-year-old daughter Cali, who is working on a business degree and hopes to one day follow in her mom’s footsteps, and her 84-year-old father. Chuck Archambault has long been retired but cares enough about the work to drop in and check up on his daughter.

“He still comes in here once a week to make sure that I am doing right by Indian businesses,” Mary says. “He keeps me on task. I will do the same for my four children and now six grandchildren. It’s important to keep the work going, even after we’re gone.”

TO LEARN MORE about the Native American Development Corporation and the work it does, visit nadc-nabn.org.