The three lives of Tiffini Gallant

Fighting Pain, Defying Odds, and Advocating for the Gift That Could Save Her Life

Tiffini Gallant has lived two lives so far. She hopes to live a third.

Tiffini’s first life spanned her mostly-typical childhood into young womanhood. Her second life came on with a vengeance, when a rare kidney disease stole her health in her mid-30s. Now, with all the energy she can muster, the young mother is determined to live a third life — but it all depends on a donated kidney.

Today, Tiffini lives in constant pain — the severity of which ebbs and flows depending on when she last received her monthly lidocaine infusion at the University of Utah Hospital in Salt Lake City. The once-active 37-year-old now lives month-to-month as she seeks a match. The disease has robbed her of her health, her job and her marriage.

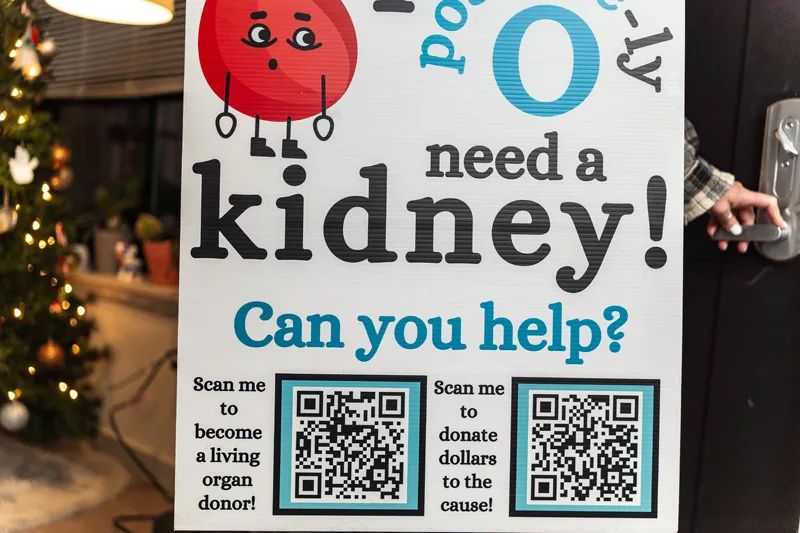

Although she finds most comfort in her “happy place” — a cushy rocker by the fireplace — she is no couch potato. During the two weeks of the month that the infusion moderates her pain, she’s working hard to educate and encourage organ donorship. Not only is she seeking her own salvation, but she hopes her efforts will offer new lives for others.

By her own description, Tiffini grew up as a “normal country kid” until the age of 12, when a rare form of pneumonia baffled her doctors and nearly took her life.

“I had no symptoms and then I was on death’s doorstep,” she says.

A chest scan to assess her lungs revealed an unrelated mass of cysts covering both of her kidneys. The diagnosis: polycystic kidney disease or PKD. As in most cases, that meant one of Tiffini’s parents carried the gene. To everyone’s surprise, it was discovered then that her biological father was asymptomatic with PKD.

“He had gone through his entire life not knowing it,” she says, adding that he’s suffering symptoms now.

PKD is a chronic disease that causes uncontrolled growth of fluid-filled cysts on the kidneys. It’s estimated that roughly 500,000 Americans live with PKD, of which about 50 percent remain asymptomatic. The other half, however, will develop kidney failure in their 50s. Tiffini, who exhibits a particularly aggressive form of the disease, has already had one kidney removed and is now facing failure of her remaining kidney.

Tiffini survived her bout with pneumonia and went on to live a fairly normal life —punctuated by an occasional brief stint in the hospital. There was no known treatment for the pre-teen, other than blood pressure drugs and a low-sodium diet — the understanding being that high blood pressure enhances the development of cysts.

She was advised against participating in sports, but otherwise lived a life similar to her peers, attending school and dreaming of her future. She had her heart set on joining the Navy and becoming a police officer.

Poised to make that dream come true — she’d tested in the top one percent of recruits — her world imploded when she was told her PKD made her ineligible for the Navy.

“My whole life was shattered,” she says.

Then, while attending college, a nephrologist dashed her other dream — her dream to have children.

“He tells me that it would be selfish of me to pass on that disease,” she says, pausing as the memory still stirs deep emotions. “Those were earth-shattering changes, that I couldn’t join the Navy and that I couldn’t be a mom.”

Yet, Tiffini refused to let her disease define her. She earned a master’s degree (online) from Georgetown University and spent more than a decade working in the Billings area, at Montana State University Billings, the Billings Gazette and A&E Design. Her work gave her purpose and opportunities to pursue her two passions: helping others and telling others’ stories.

In her off hours, she practiced yoga, volunteered at the Salvation Army and enjoyed the role of partner in her young marriage. In her early 30s, her life took yet another turn when nephrologist Heather McGuire offered a new take on Tiffini’s crushed dream of motherhood.

“She said, ‘Well Tiffini, do you wish you weren’t born?’,” Tiffini recalls. “That was such a powerful statement to me.”

Tiffini knew it’d be a high-risk pregnancy, but she was willing to take the chance.

“It’s a fifty-fifty toss-up whether your child could inherit PKD,” she says. “But I was so inspired by that advice. We decided ‘Let’s do it!’”

Ultimately, Tiffini gave birth to a healthy baby boy — Holden — although the pre-eclampsia she had experienced toward the end of the pregnancy took a toll on her kidney function.

Yet she returned to work for several years, until a kidney cyst ruptured while she was at her desk writing. The excruciating event led to an infection that precipitated her second life, a life of chronic pain.

During one period she spent more than a year virtually bedridden, taking narcotics to get through the day while simultaneously attempting to care for her toddler son.

“At times, I couldn’t bathe myself. I couldn’t get out of bed. I couldn’t stand upright,” she says. “We thought there is no way this could last.”

But it did. Unable to work she saw no option but to apply for disability. She describes the process as “grueling.”

A visit to Mayo Clinic, where she saw Dr. Vincent Torres, known as the “Godfather of PKD,” confirmed what she was experiencing.

“A certain percent have rapidly progressing polycystic kidney disease,” she says. “He said it was just my genetic lottery.”

As the pain took control, she tried fentanyl patches, acupuncture and nerve blocks to no avail. She was prescribed the drug, Jynarque. At $21,000 a month, it’s the first drug to gain approval for patients with the aggressive form of PKD. As Tiffini’s pain persisted, surgeons decided to remove Tiffini’s excessively enlarged left kidney to allow more room for her right — hoping it would offer relief. But the pain proved relentless.

This summer, when her kidney function dropped below 20 percent, Tiffini celebrated. The news meant that she finally qualified for a kidney transplant, a life-saving procedure that might still be years into the future.

“They told me to expect four to six years,” she says. “That took the wind out of my sails.”

While the role of donor is much less arduous than that of a recipient, she knows it’s still a big ask. But it’s a big ask she takes on as her current mission in life.

Meanwhile, she strategically plans her activities around the monthly treatments that offer her moderate relief. She started a support group for others who deal with chronic pain and illness and she’s authoring a memoir in which she deals with the impacts of chronic pain on one’s mental health, finances and relationships. And when the muse moves her, she writes poetry, referring to herself as the “Not Dead Yet Poet.”

“It’s a creative outlet and gives me the ability to laugh and spread awareness,” she says.

Last year, as her condition worsened, she was recognized in the Gazette’s “40 Under 40.”

As Tiffini faces the prospect of dialysis, she’s thankful for support from family and friends. Her parents have relocated from Florida to Montana to assist her and a sister is currently undergoing testing to see if she might be a match.

“She’s actually told me since she was 12 years old that she wanted to give me a kidney when the time came,” Tiffini says.

Besides her own prognosis, Tiffini was dealt another blow that brought her to her knees. Noticing blood in Holden’s urine during potty training, she had him tested.

“He does have it,” she says.

Today, Tiffini relies on weekly therapy to keep from being consumed by despair. She was particularly moved when her therapist suggested a new perspective on the future of mother and son.

“She said, ‘Who better to model for Holden how to face the adversity of his disease than his mother?’” Tiffini says, “That gave me purpose.”

Purpose continues to drive Tiffini as she promotes organ donation. Even if one donor’s kidney is no match for her, there’s a likelihood it will help someone else. And it may allow Tiffini to move up the waiting list.

“I can’t say I’ll ever go back to the life I lived,” she says, “but the prospect of living a life free of chronic kidney pain and complications is nearly unfathomable. It’s enough to give me hope.”

Tiffini clenches that fragile thread of hope as tightly as she can. She is determined to live her third life.

Becoming a Live Organ Donor

Understanding the Journey, the Risks, and the Resources

· All adults in the United States — and in some states people under age 18 — can sign up to be an organ donor.

· The process involves a thorough medical and psychosocial evaluation to ensure the donor is a good candidate.

· If approved, a date will be set for surgery. The procedure for a kidney is often laparoscopic.

· Recovery will likely involve a brief hospital stay, typically one to three days and will bring some pain, discomfort and exhaustion.

· The recipient’s insurance will typically cover medical expenses while the donor may be eligible for financial assistance for lost wages and travel.

· The risks are considered low but can include allergic reactions, bleeding, infection blood clots and exhaustion.