The Weight She Carries, The Light She Shares

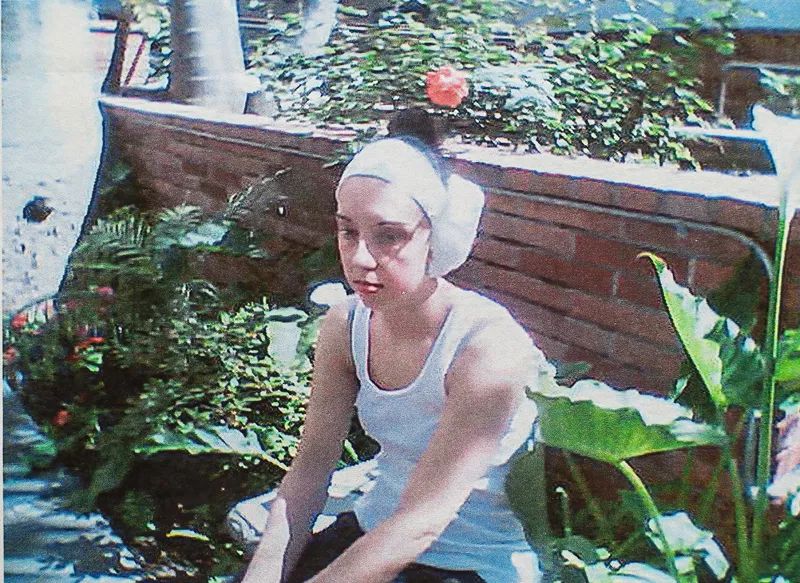

Ricki Wolfe Ochoa’s journey from trauma to lifeline

When her phone rings late at night. Ricki Wolfe Ochoa doesn’t hesitate to pick up. She knows the other end of the line could bring a shaky voice or a life-or-death intervention. She understands deeply how critical these moments can be in saving a life.

“There’s not a phone call I won’t take,” Ricki says. She likes to think she shows up in people’s darkest moments. And, she understands personally, the need to have someone in your corner.

“I had a very tough childhood,” Ricki says simply. “I suffered some severe traumas along the way.”

She was 7 when her parents split. That meant summers in Montana with her dad and winters in Florida with her mom. The two worlds couldn’t have felt more different. Montana was laid back and carefree. In Florida, Ricki’s mom worked three jobs just to keep a roof over their heads.

“I learned to fend for myself at a really young age,” she says. The experience not only gave her a deep empathy for those struggling with life.

But even with that strength and perspective, her path grew more complicated in high school when she found herself pregnant at 17.

“I was terrified,” Ricki says. “It was a pivotal moment for me. I thought, ‘Should I terminate my pregnancy?’ My faith said, ‘No.’ One day, I looked up into the sky and I said, well, you know, if you do this, she is still going to be there. You will always be a mom.” Nine months later, her daughter Nevaeh was born.

Soon after, Ricki enrolled in college and planned on becoming a nurse. About that same time, she started experiencing dizzy spells and severe headaches. Every few weeks, she’d end up in the emergency room in extreme pain.

“They told me I had vertigo,” Ricki says.

Yet one more trip to the ER uncovered the truth.

“I had a domestic violence incident and went to the emergency room because my head was pounding.” She remembers the medical staff telling her, “You are negative for trauma but we found a pretty good size tumor on your brain.”

The diagnosis was acoustic neuroma, a benign tumor that had been slowly growing near her brainstem since youth.

“I had lost 60% of my hearing in one ear and didn’t even know it,” she says. “I got out of surgery and they broke the news that they couldn’t get it all. They did get it off the brainstem so that I could survive.”

Five months later came a second surgery to try to get more of the tumor. While they were able to do so, her surgeon told her trying to take the entire tumor could have sparked a major, potentially fatal stroke.

Sadly, that procedure resulted in a cerebral fluid leak, bringing yet another surgery. Doctors had to shave muscle from her face to seal the leak and grafted it all in place. Nerves were severed in the process, limiting the feeling on the left side of Ricki’s face. “I have optic-nerve damage. They gutted the ear canal,” she says, meaning she lost all hearing in her left ear. The nerve that controls balance was also severed.

When she awoke from surgery, “I remember saying to myself that the pain was so bad that I didn’t even care if I lived,” Ricki says. “That was a tough moment for me.”

By her junior year in college, she was struggling to put the pieces of her life back together when one of her professors at Montana State University Billings sat her down.

“She asked me, ‘Why are you doing this (nursing school) when you wanted to be a counselor?’”

The unexpected question ended up changing the course of her life.

“I always say this career chose me,” Ricki says. “It goes so deep. I genuinely feel this is who I am and who I am supposed to be.”

Ricki not only got her bachelor’s degree, but by 2010, she completed a master’s in mental health and rehabilitation counseling. When she walked across the stage to receive her master’s degree, her brother Michael was there to cheer her on. It was one of the last times she’d see him.

“He left us a video of why he did it,” Ricki says of her brother’s suicide. “He said, ‘All my life I have found ways to cope and at this stage in my life. I have no coping methods anymore.” Ricki pauses, then says, “It was the most brutal thing.”

Her brother shot himself in a field on their father’s farm.

“For him, it was a lack of getting any mental health care and just thinking he couldn’t handle it all,” Ricki says. His death has become a driving force in her counseling practice. After working for others for a number of years as a licensed clinical professional counselor, last July she opened her own practice, Zoetic Therapy. The word zoetic means “living” or “vital.”

“My brother is with me every day. In every session I do, there’s a piece of him here,” Ricki says.

When she goes to work each day, Ricki makes it her mission to teach others how neurological impairments impact mental health. These types of injuries cause physical changes to the brain and can alter how emotions are regulated. That makes standard treatments less predictable. Suicidal tendencies rise. Traditional antidepressants often fail to work.

“This is where we lose people,” Ricki says. “They give up.” Ricki has heard her patients tell her many times, “I'm not responding the way I should be to the pills. I don’t feel the way they say I should.” Ricki’s response? “Let’s talk about it.”

Brandee Pacheco can’t thank Ricki enough for her perspective.

“I shouldn’t be alive,” Brandee says. On Sept. 3, 2021, she was riding on the back of her ex-husband’s motorcycle when he decided to go around a vehicle that was turning. He didn’t see an oncoming car.

“The other vehicle took us out,” Brandee says. “I flew 25 feet into the air and landed on my head. I was in a coma before the firemen even got to me.”

After being treated at a Billings hospital, she was eventually flown to Craig Hospital outside of Denver, a facility that specializes in brain injuries.

“My temporal bone was broken,” Brandee says. “I had a hole in the back of my skull. My fingers were broken. I had nerve damage. I couldn’t close my right eye.” Doctors warned her family that with her type of injuries, suicidal thoughts were common.

Within that same year, those thoughts rose to the surface. Brandee even planned her suicide for a night when her two daughters would be away. She says, “Unfortunately, one of my daughters came home early.”

That’s when Brandee found Ricki.

“She made me talk through things that no one has ever asked me about. She helped me work the parts of my brain that she could tell caused frustration,” Brandee says, adding Ricki helped her find ways to work around those frustrations. And, she helped Brandee set up a safety plan.

“When you are in a crisis, your brain shuts down,” Ricki adds. Her instruction to Brandee was simple: “Here’s what we are going to do when we feel this way. You don’t even think about it, you go to the safety plan.”

Brandee’s plan was to immediately call her best friend. The friend would call the authorities, and the second call would be to Ricki.

Brandee explains that her safety plan involved a code word.

“That meant my friends needed to get to me now,” she says. “Ricki taught me a way to express my feelings. If I am thinking it, I write it down. I get it out of my mind and off my chest.” Brandee goes on to say, “I needed to heal but I didn’t know how. I’ll probably never be who I was but, I’m getting back to being close to who I was.”

Thanks to her healing journey, Brandee has been able to watch her children grow into adults and she got remarried to a man she says brings out the best in her.

“God put her in the right place at the right time,” Ricki says.

There are days when Ricki has to dig deep to get through the day. Scar tissue from her brain surgeries bring daily headaches. When a migraine strikes, it’s next-level. When you ask her how she lives life with daily pain, she says, “I look at everybody around me that has a story. Everybody has one. The second I think my story is challenging, I find inspiration in someone else’s.”

Today, Ricki is happily married and has two daughters — Nevaeh and Aariah. Within the next few years, she would love to go back to school to get her doctorate in neuropsychology so she can better serve her clients. Right now, Ricki can’t perform neuropsychological exams and the wait can be upwards of a year for those in need to have them. It’s valuable time when a diagnosis awaits.

Ricki still gets a brain scan every two years so doctors can keep an eye on the tumor that’s still living near her brain stem. Knowing just how precious life is, Ricki says, “I always have something on the horizon to look forward to. That’s big for me,” Ricki says. “I encourage everyone I know to dream a little.”

She also wants those she comes in contact with to know they aren’t alone. Ever.

“You are not weak if you ask for help. You are actually strong,” Ricki says. “The big picture here is, we want you here. We need you here.” She pauses before adding, “We are all in this together.”